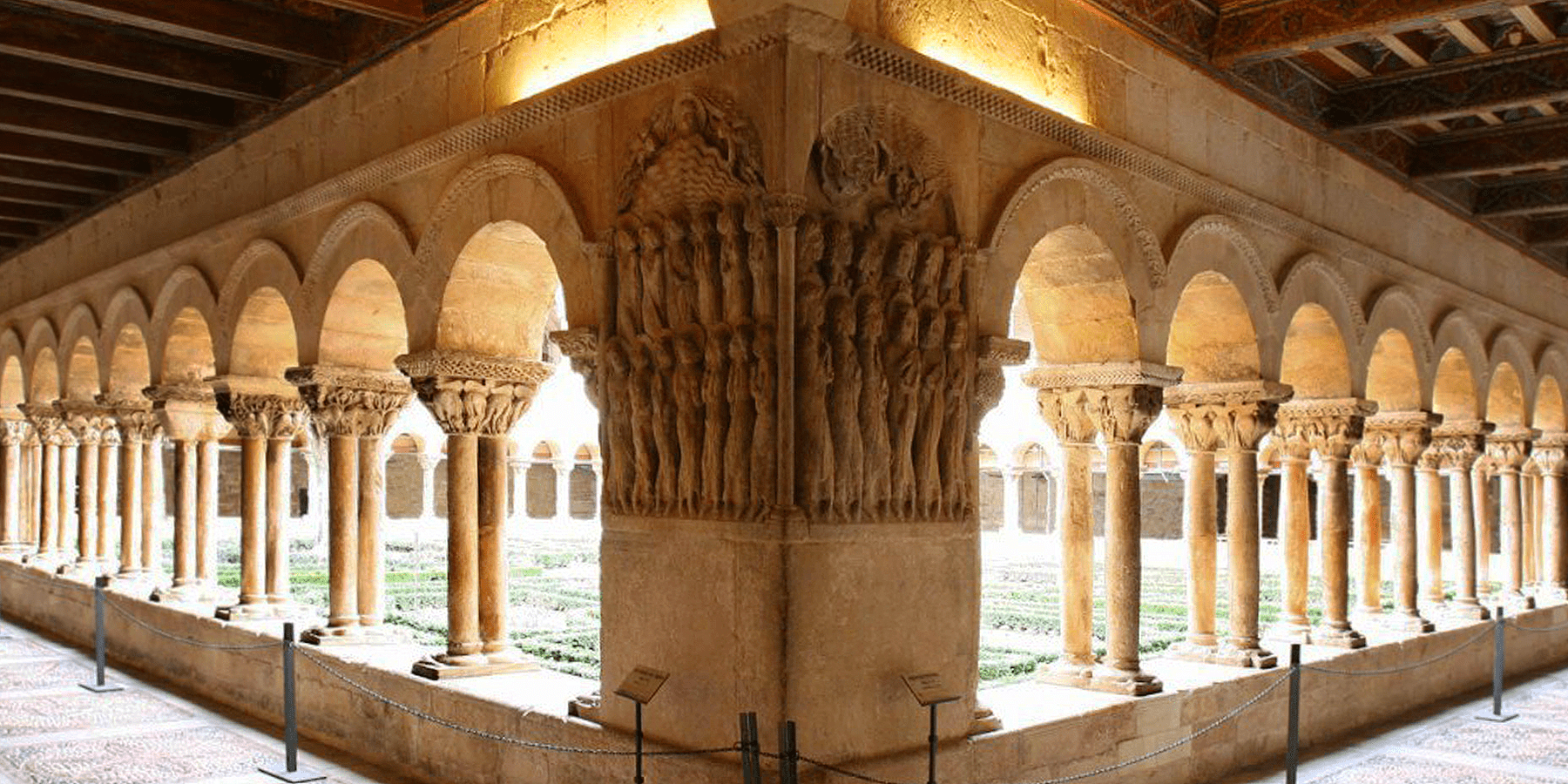

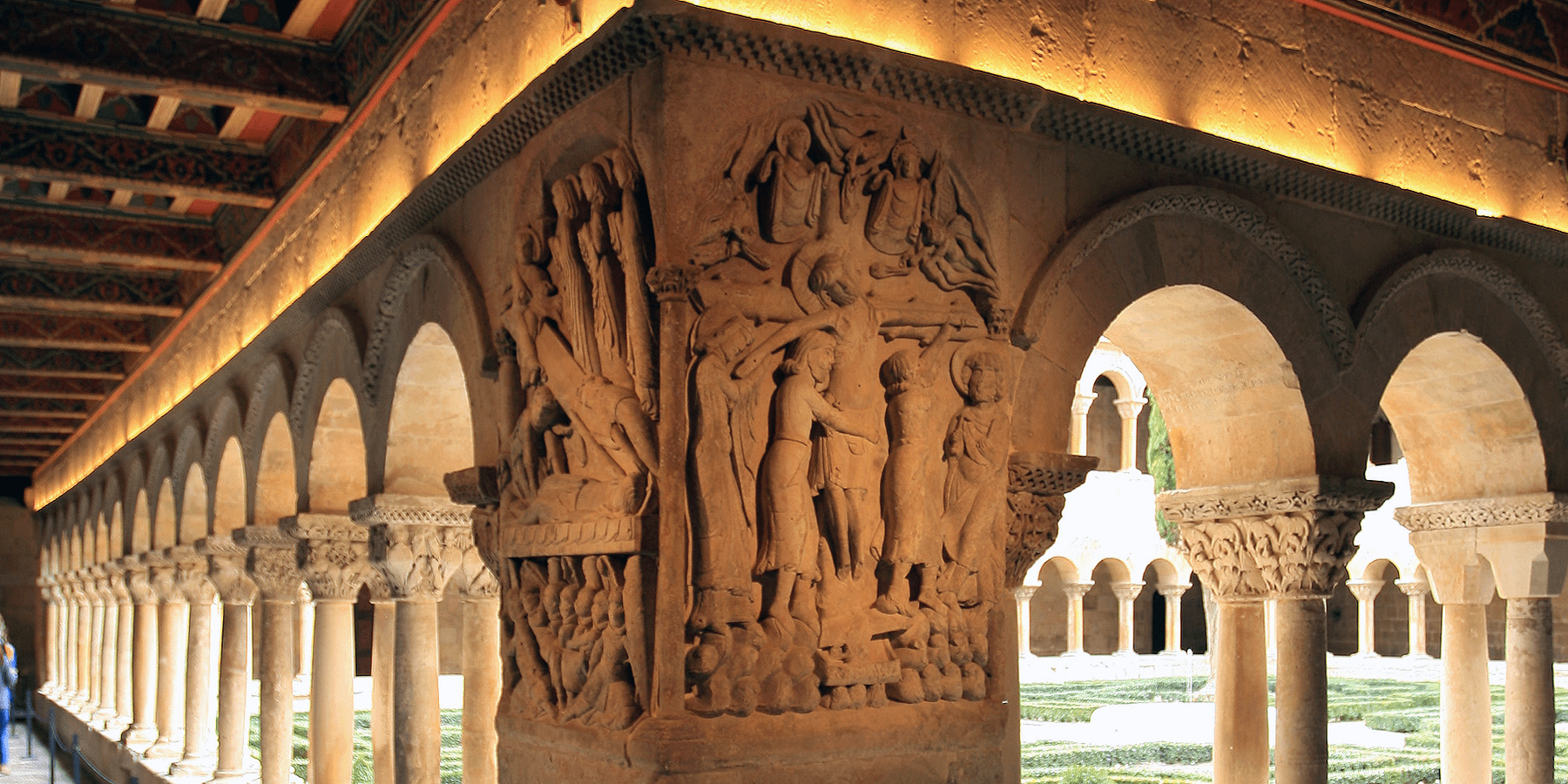

The cloister is one of the sacred “centres” of the medieval monastery. With its openness to the sky, it rose the monks above the visible, and at Silos, images of pilasters and capitals enhanced the link between heaven and earth.

On the corner pillars, scenes of the death, resurrection and glorification of Christ emphasised his need for mortification. The capitals, through animal figure reflecting literary traditions that were prominent in the Middle Ages, depicted human behaviour with qualities and defects and, in short, constituted a perfect mirror in which the monks could contrast their yearnings for regeneration and virtue.

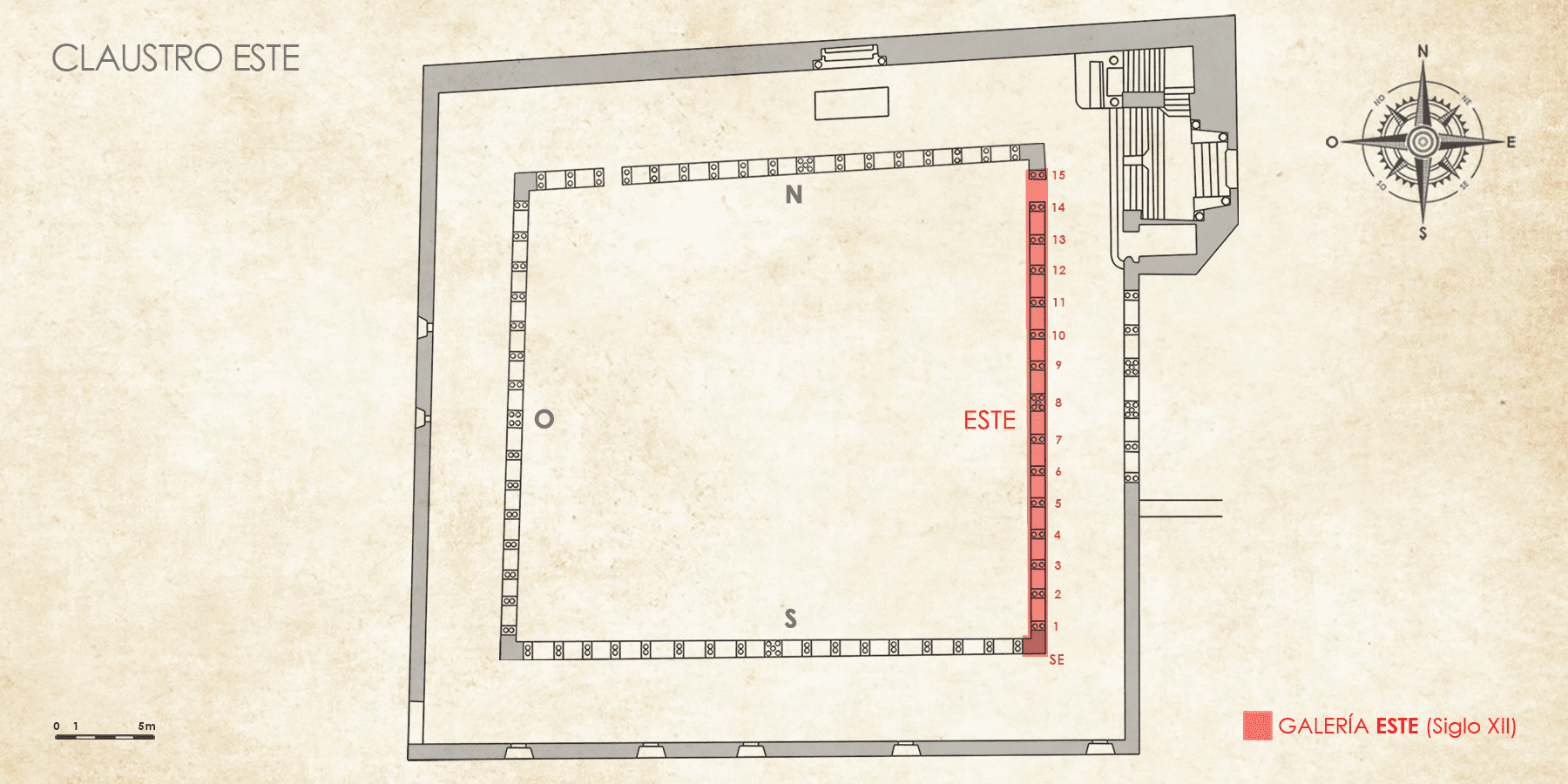

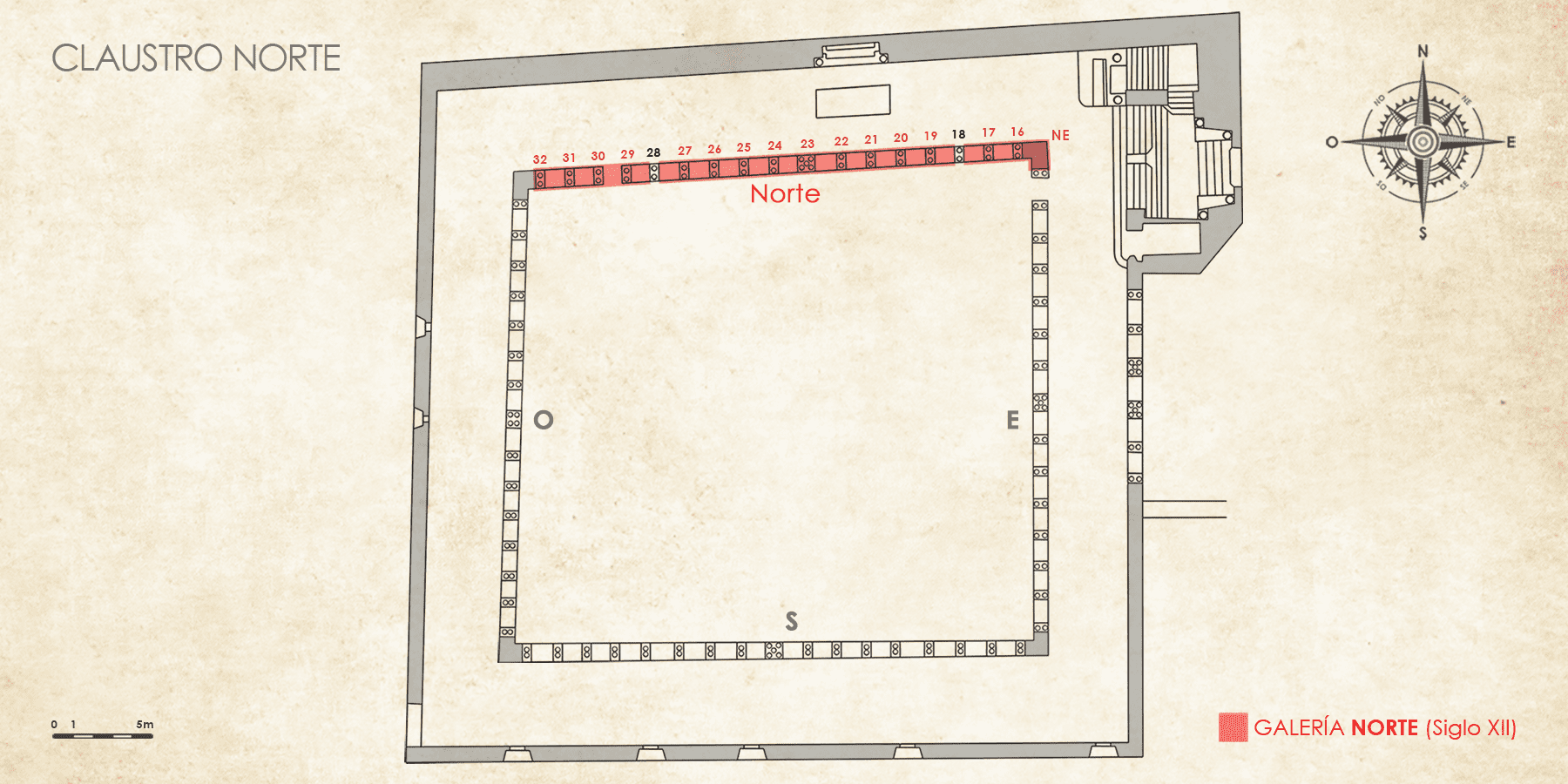

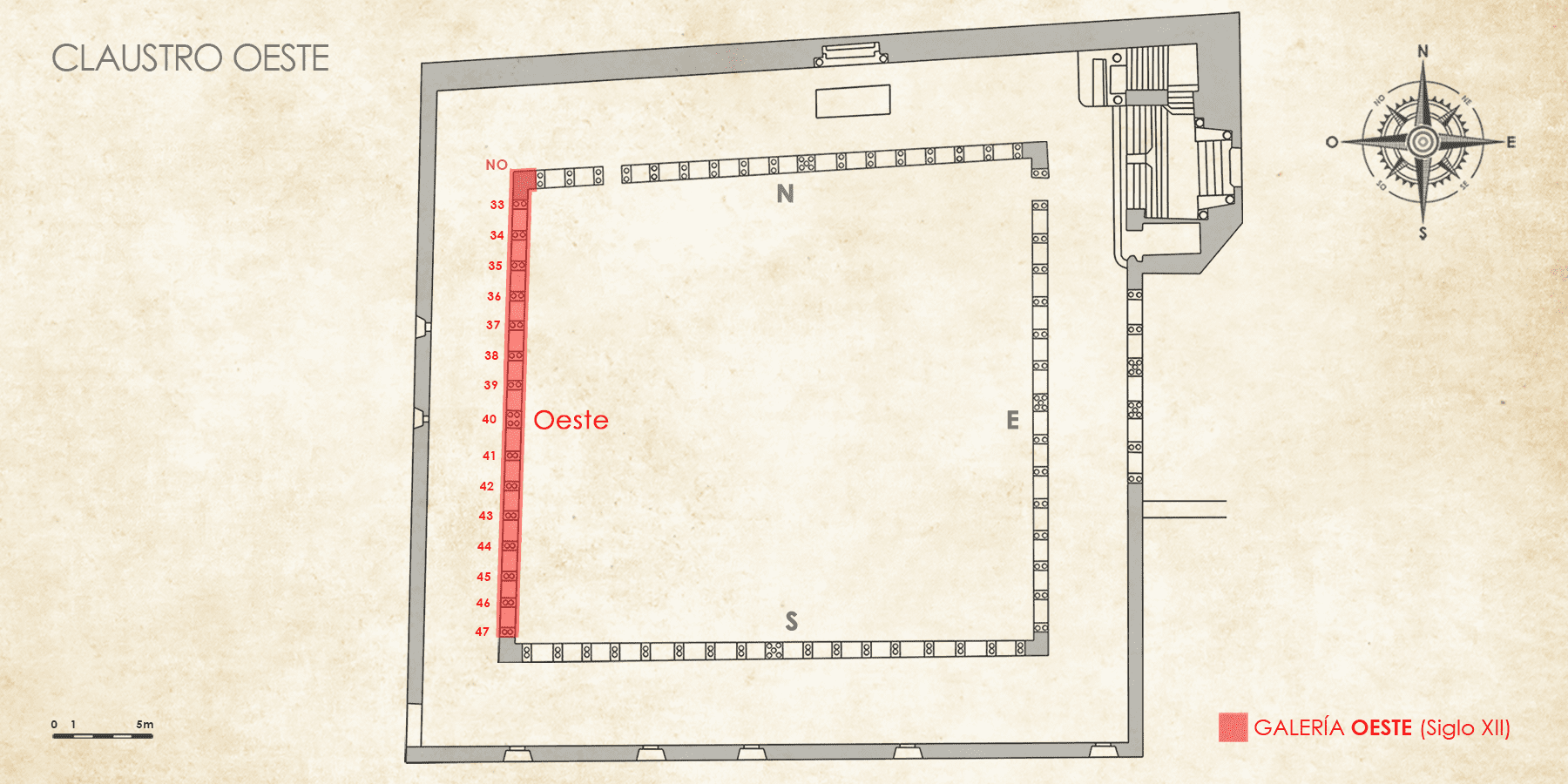

The explanation of the pillars and capitals begins on the east-facing side of the Chapter Hall. It was the first to be built to facilitate the monks’ access to the Chapter Hall. In this eastern gallery and in the northern and part of the western galleries, the pillars and capitals were sculpted in the late 11th-early 12th centuries and correspond to the oldest part of the cloister.

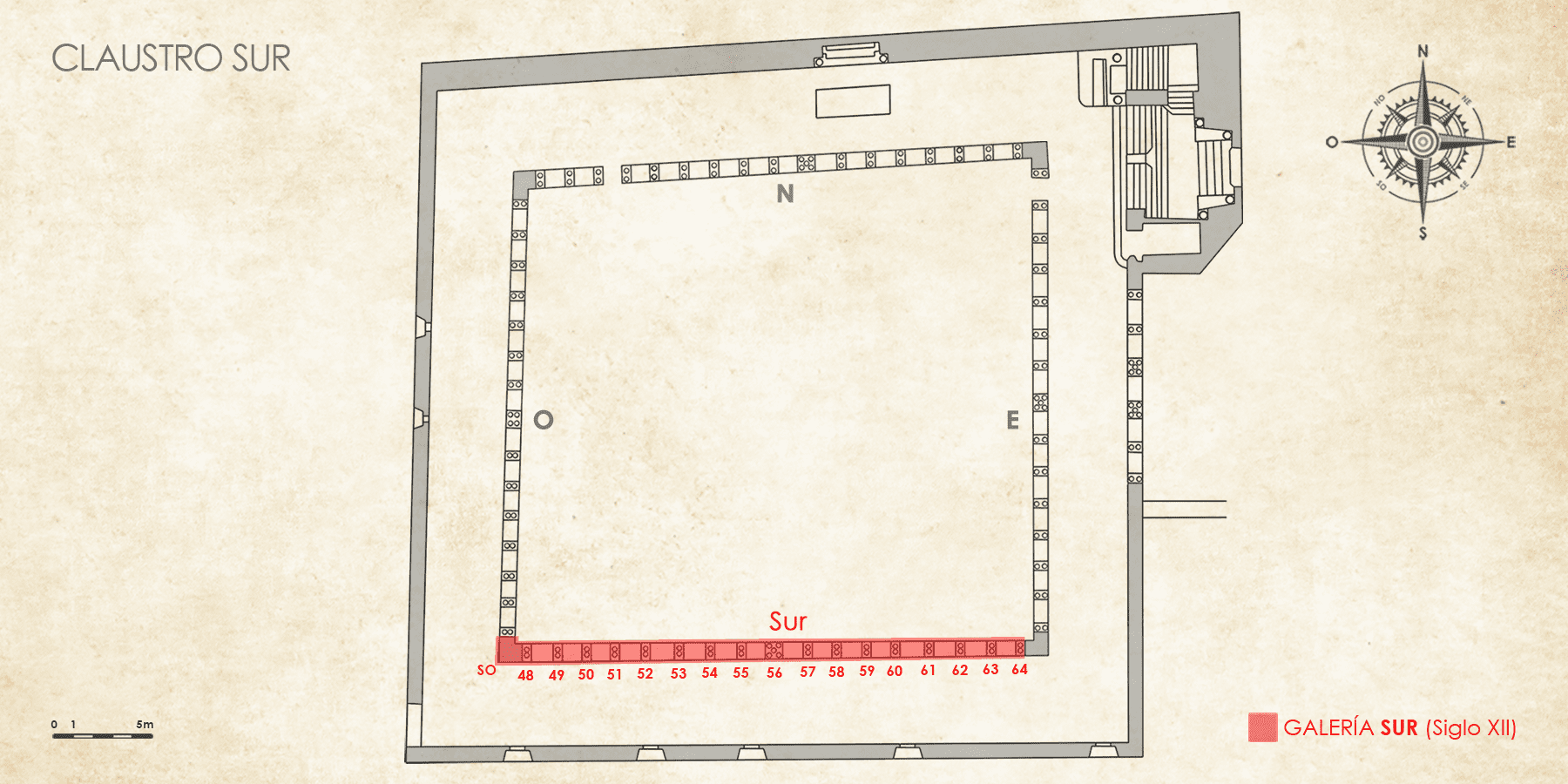

THE LOWER CLOISTER: ICONOGRAPHY AND MEANING OF CAPITALS AND PILASTERS

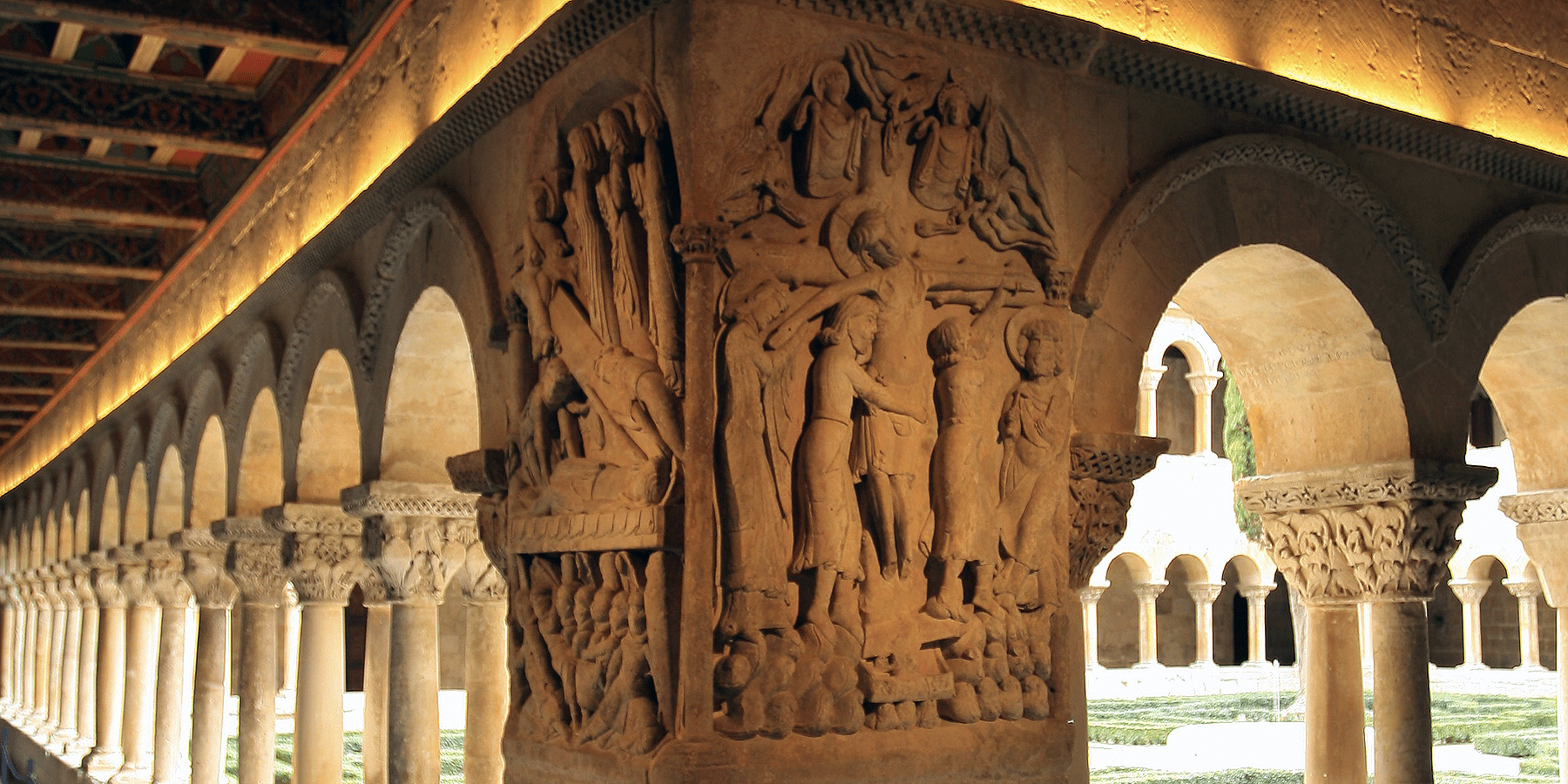

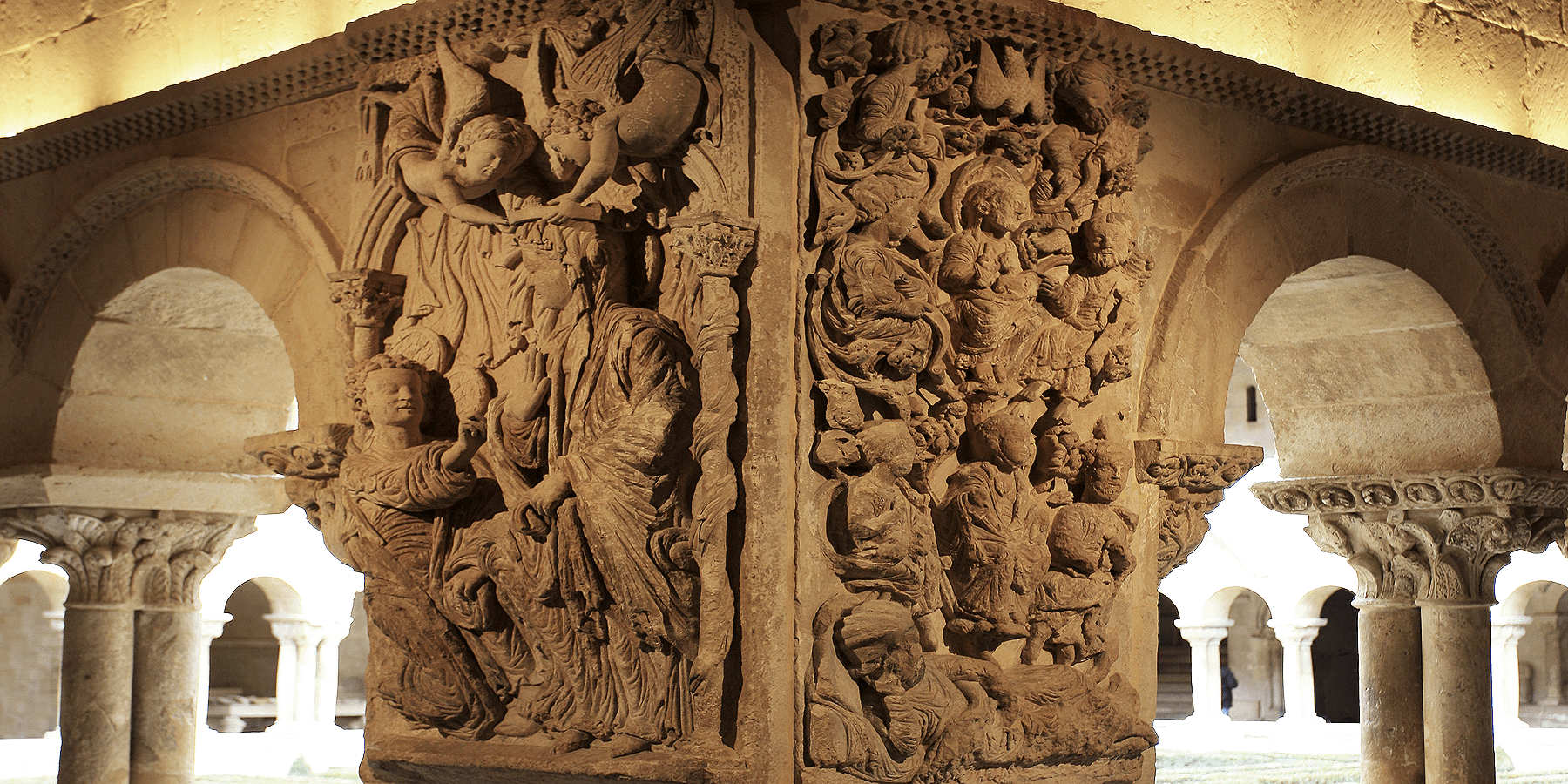

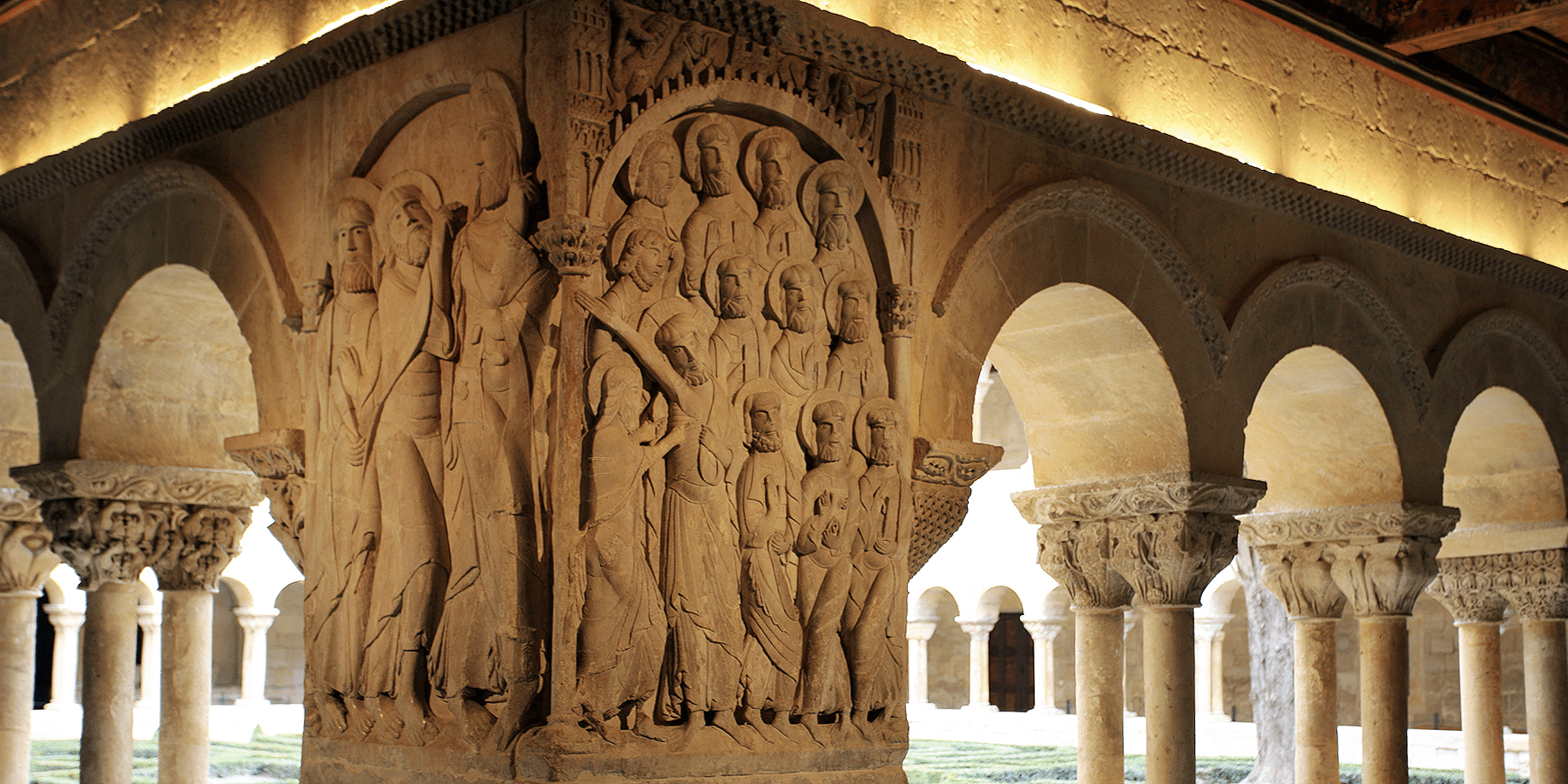

RELIEFS OF THE SOUTH-EASTERN PILASTER: ASCENSION AND PENTECOST

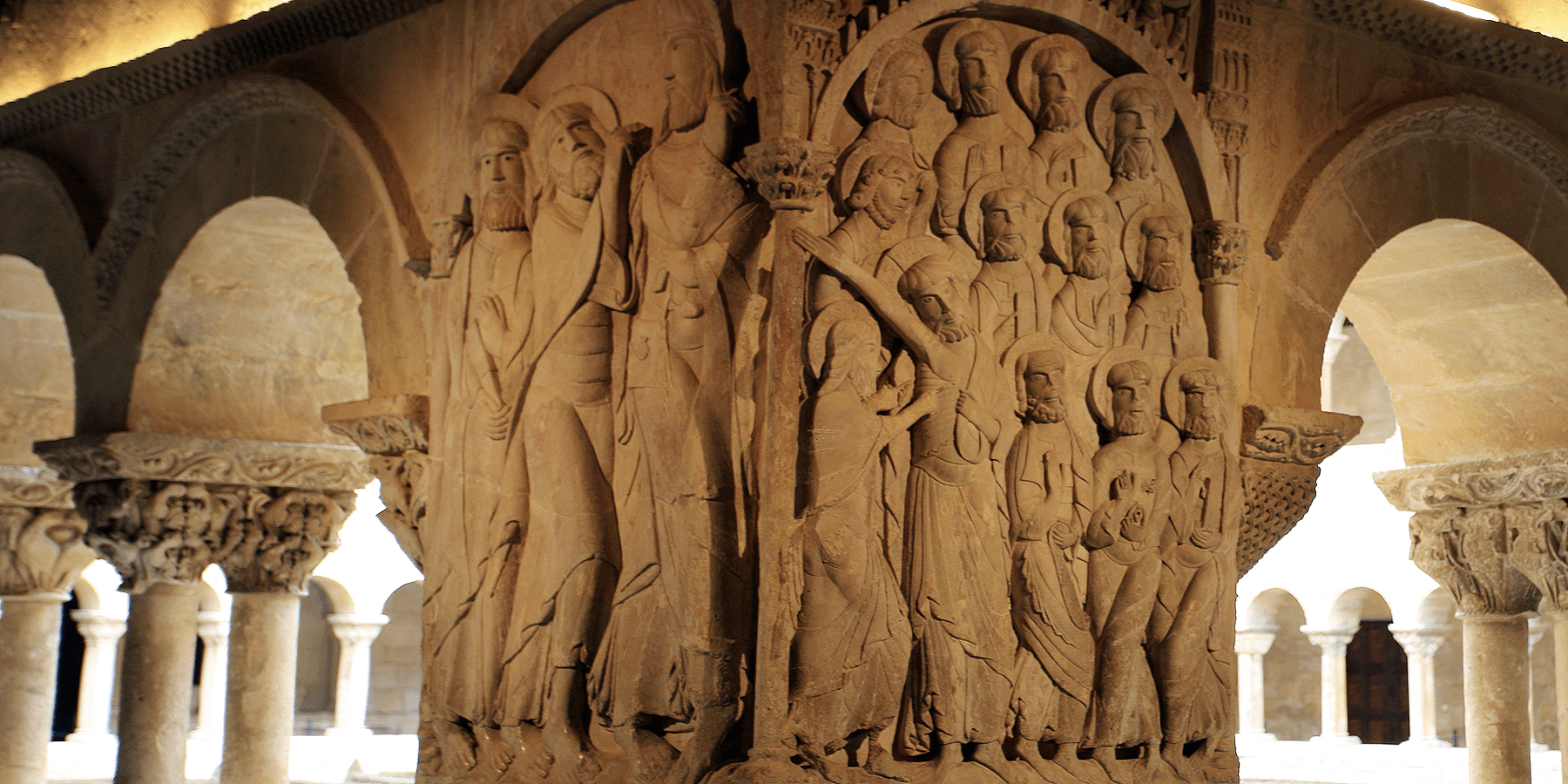

The first panel depicts the Ascension of Christ and the Pentecost – the coming of the Holy Spirit to give the apostles the gift of wisdom. In both scenes the composition is very similar.

In the Ascension, in a double superimposed row, the apostles and the Virgin Mary appear looking upwards. The inscriptions on the halos also reveal their identity. Mary is in the upper row, between Peter and John: Peter with his inseparable key and John clutching the Virgin’s mantle as an expression of the closeness between the two, entrusted by Christ himself on the cross. Paul, behind John, is not lacking in this apostolate either, recalling the establishment of the Church with a universal vocation.

At the top, clouds climbing upwards which are held by angels peeping out from between adjacent clouds, reveal the head of Christ with a cruciform halo. Instead, they hide the body of the Lord ascending to heaven (Acts 1, 9-12).

In the Pentecost meanwhile, consistent with its meaning, the descending sense prevails. Also, at the top of the relief, this time the clouds hang over the figures, enveloping a hand in the centre and the adoring angels on either side. At Silos, the hand represents the Holy Spirit and hangs above the apostolate, arranged in two superimposed rows, as in the Ascension. Again, the halos on their heads detail their respective names – Paul and the apostle John, with an air of solace, convey the reception of the Spirit.

RELIEFS OF THE SOUTH-EASTERN PILASTER: ASCENSION AND PENTECOST

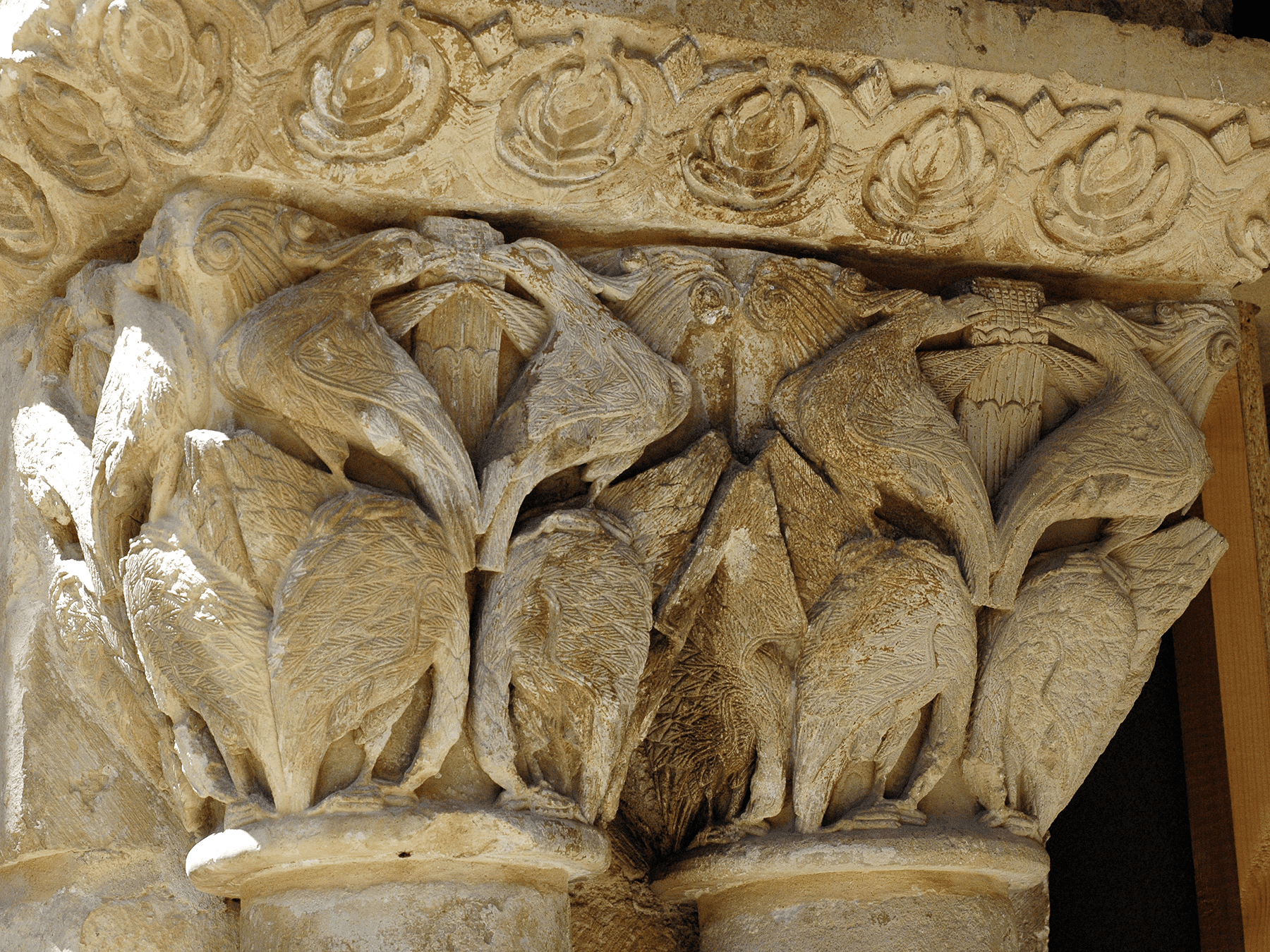

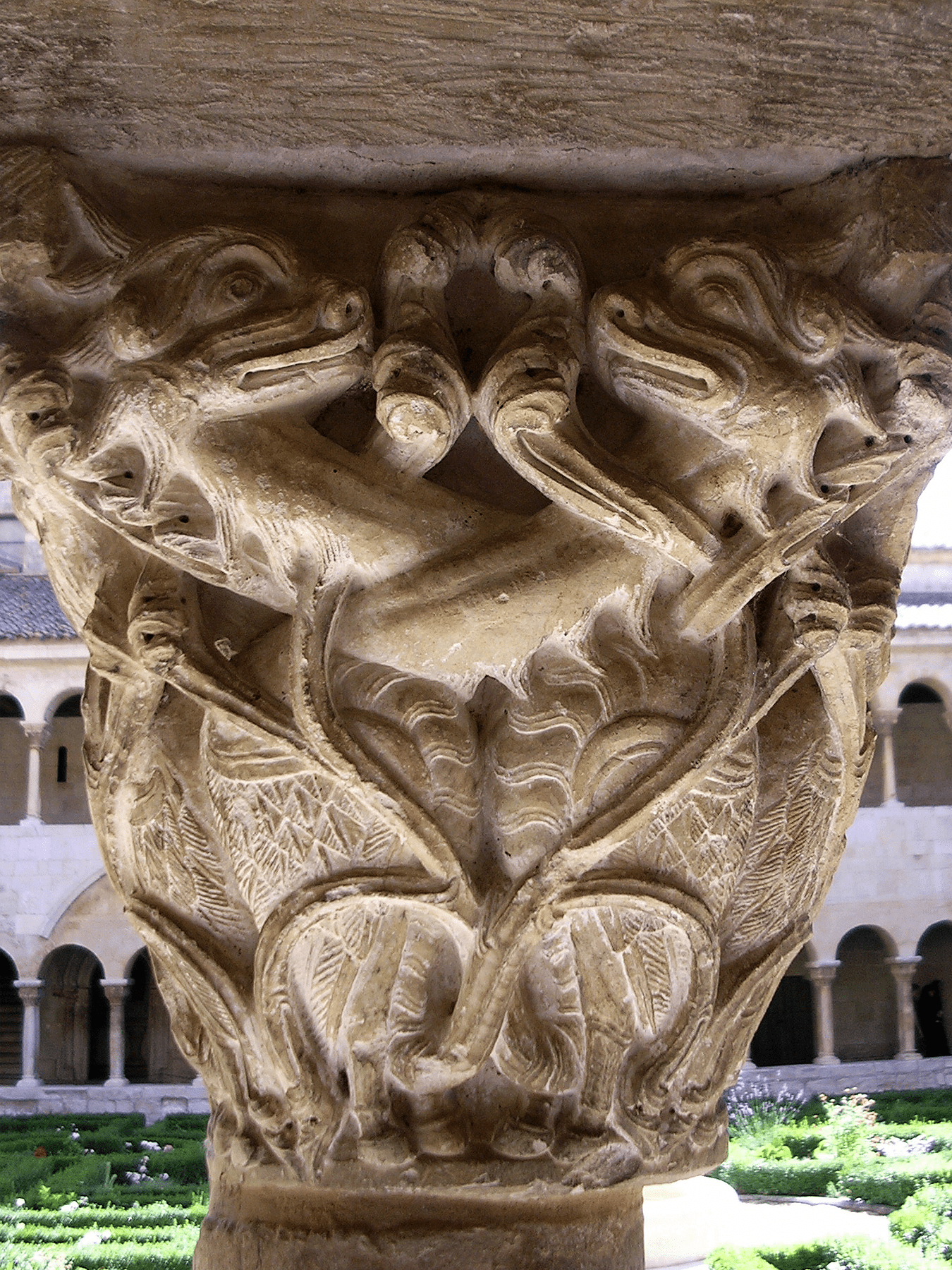

Capital 2. Pelicans

Pelicans intertwine their long, slender necks to peck each other’s thighs. The bird’s appearance, its claws topped with nails and its thick, curved beaks, are reminiscent of a bird of prey. This is clearly not a real pelican, but in the art of the High and Early Middle Ages it appears in the form of a bird of prey.

According to ancient naturalists, pelicans, after seeing their young die, would tear their bodies apart so that the dripping blood would bring the chicks back to life. Here, in Silos, the thighs are, in fact, the target, with the Christianised story of the pelican – an allegory of Christ: He also shed His blood on the cross so that man could be brought back to life through the remission of sins.

“I became like the pelican in the wilderness”. It is the cry of a man in solitude who, in Psalms, implores Yahweh. The monk in the monastery, far from the worldly, is similarly likened to the pelican in the wilderness. Both are the image of the loner.

CAPITAL 2. PELICANS

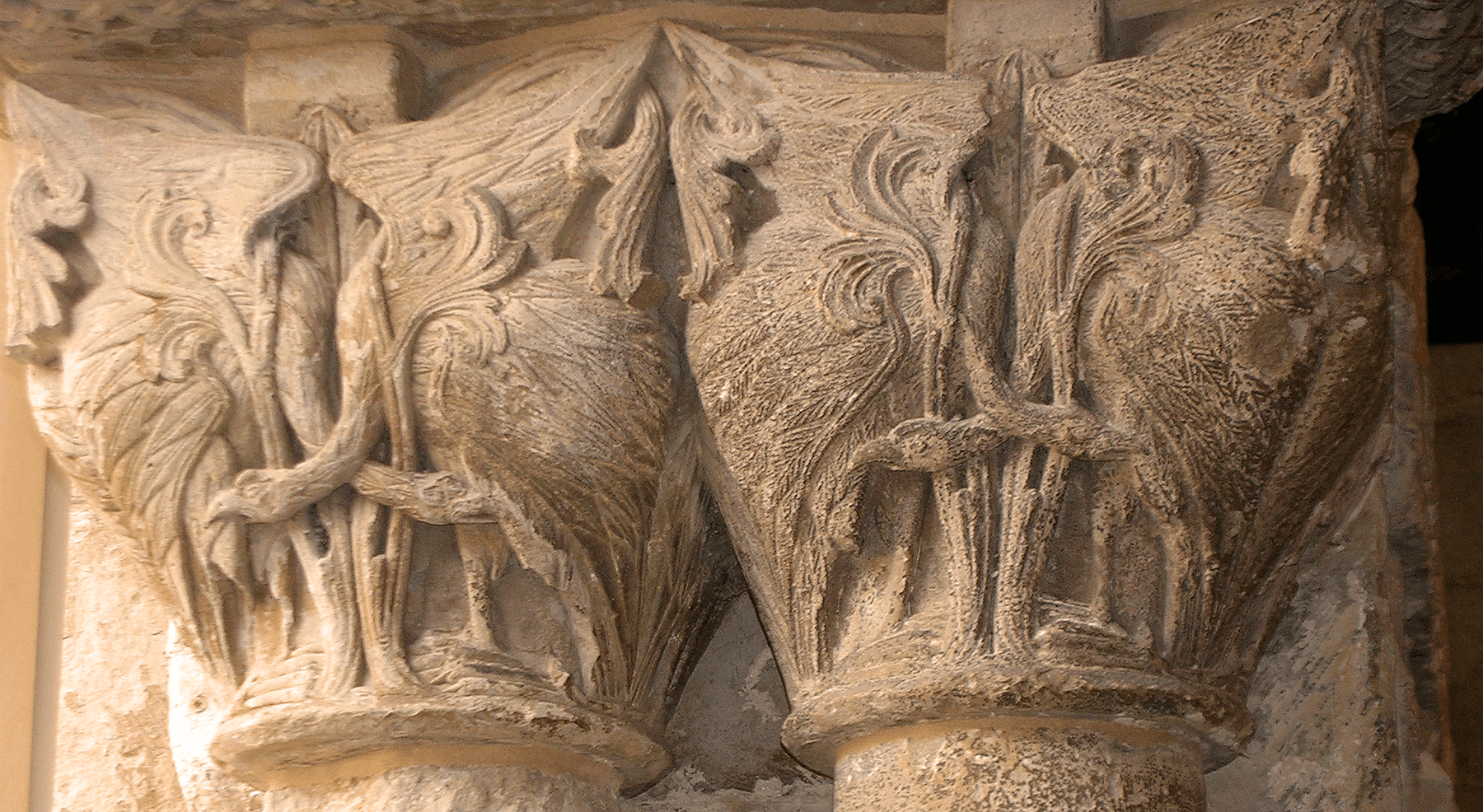

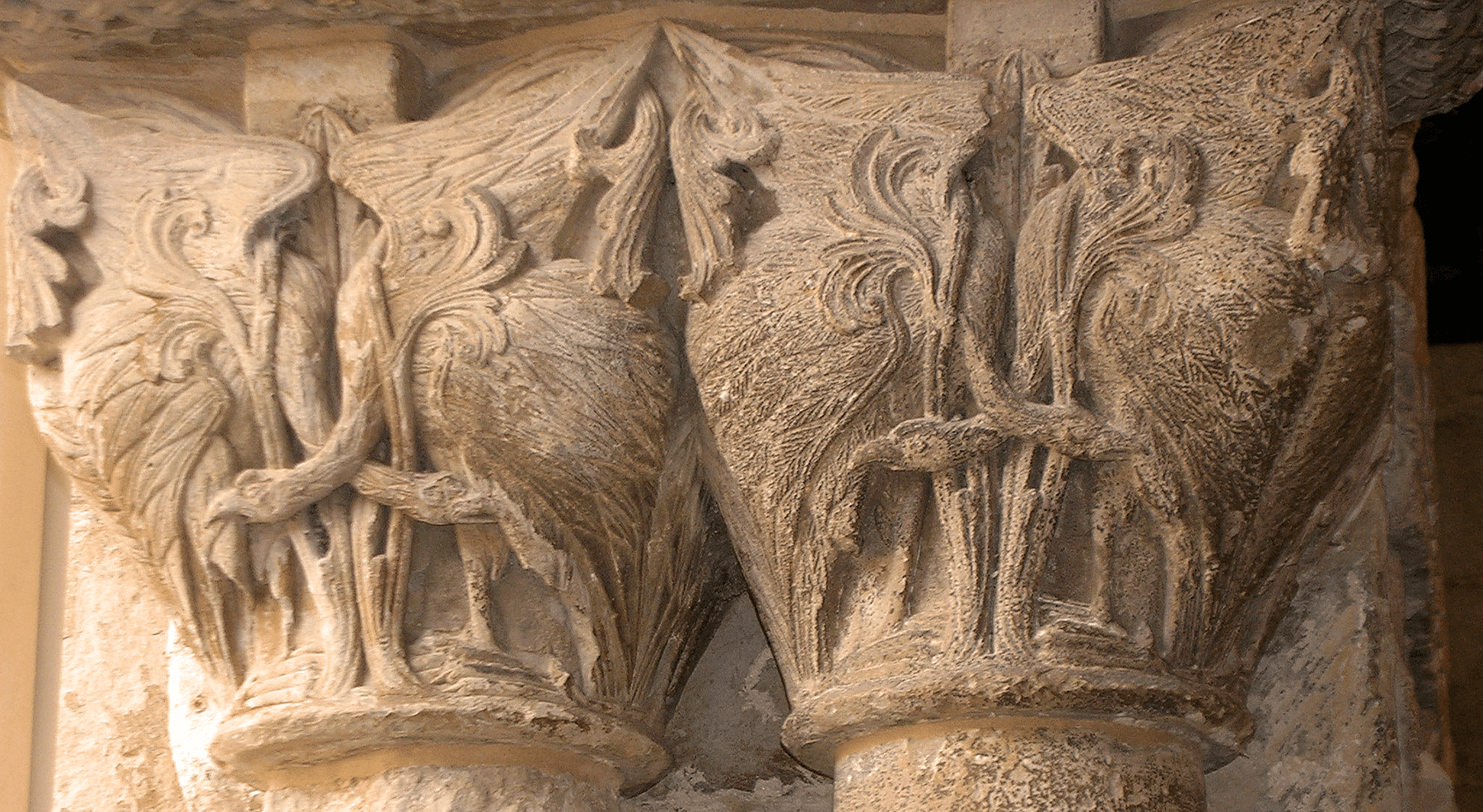

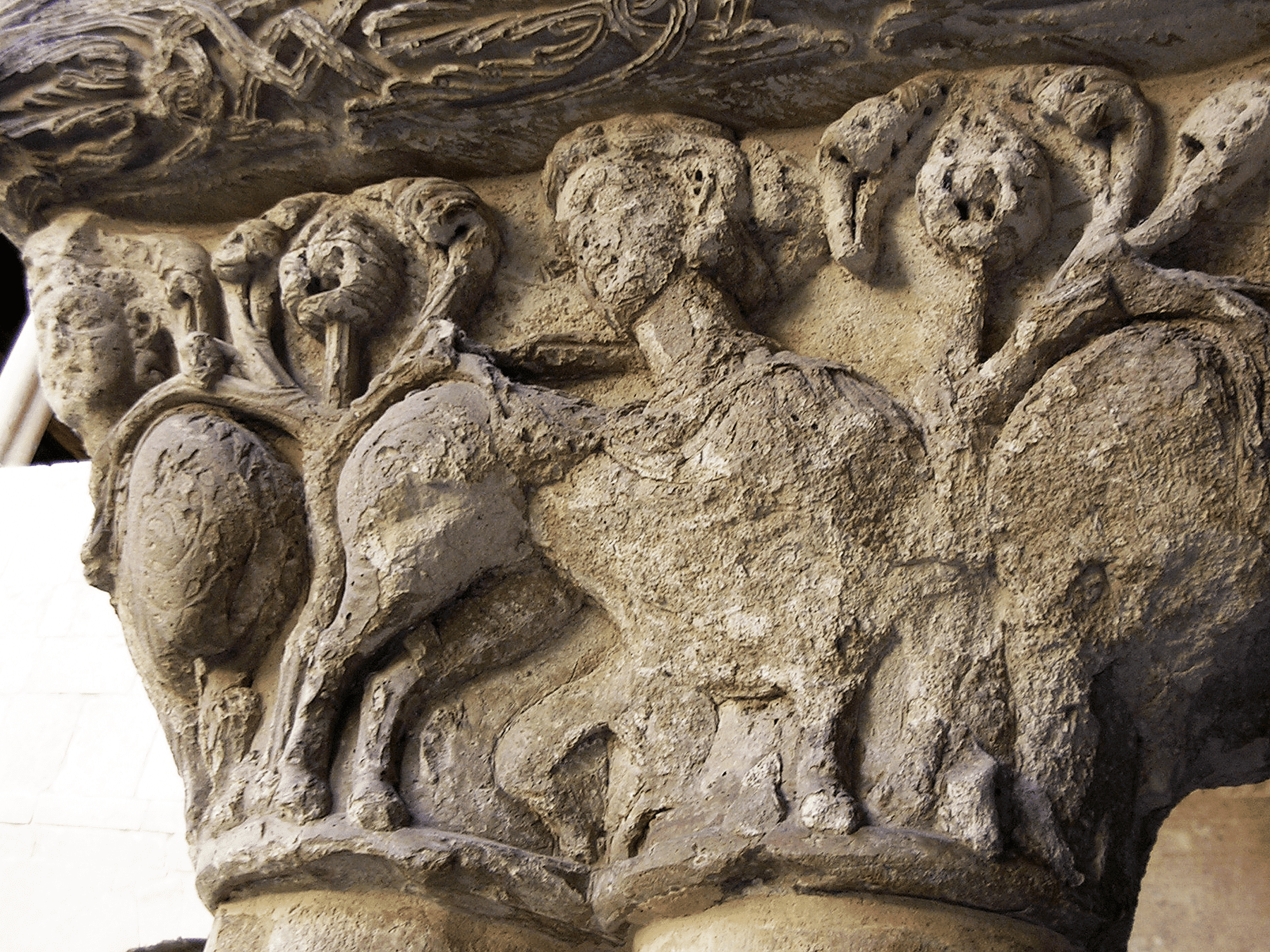

Capital 3. Vultures

The vulture has its most peculiar features: a bare head down to the neck, robust, curved beaks, sometimes with a ruff, and large bodies covered with long, broad wings. The long, pointed nails of their claws perfect the image. They attach and oppose their heads in order to peck at each other’s wings.

In Ancient Egypt, the vulture symbolises the mother-goddess of the sky and the naturalists of Antiquity, evoking the myth, recreate a bird, unrelated to the male, always female, which reproduces, without sexuality, thanks to the wind. The Christianised fable places the vulture on the “eutocia stone”, originally from India, to avoid the pain of childbirth. Virginity emerges in the form of the bird: it is Mary. Meanwhile, the “eutocia stone” represents Christ.

CAPITAL 3. VULTURES

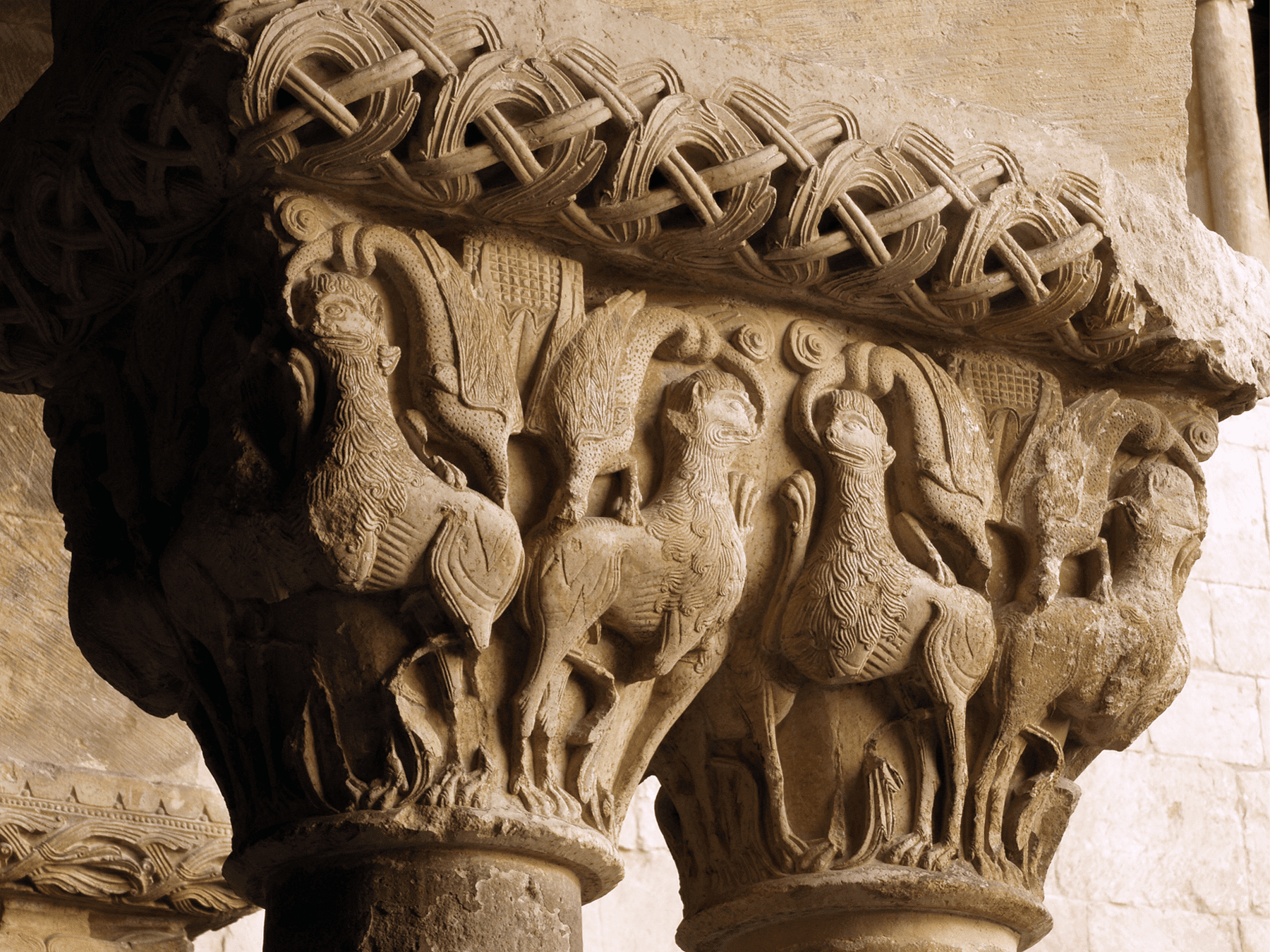

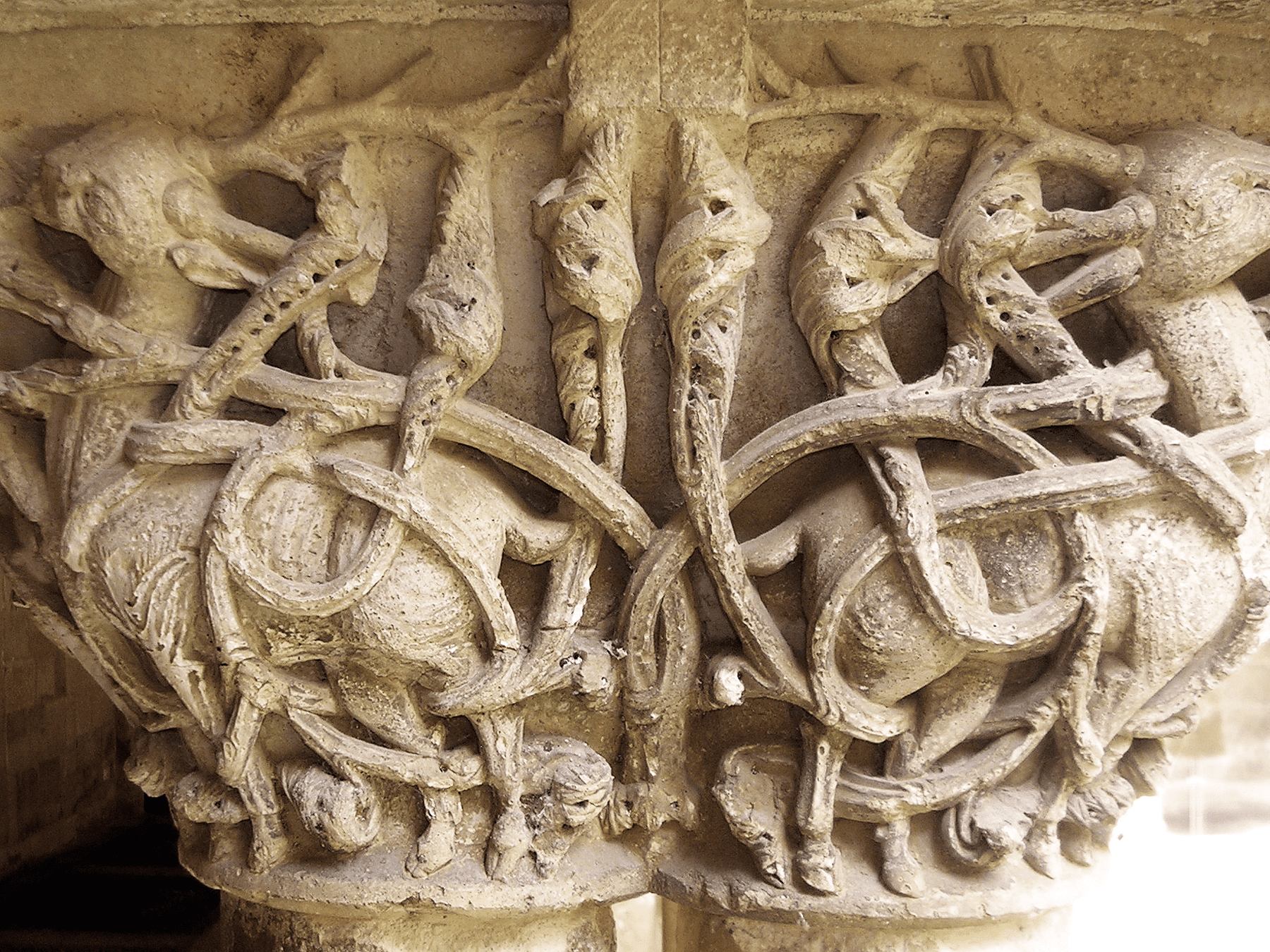

Capital 4. Lions and dragons

The lion shares the spotlight with the mythical dragon. Paired together, they bite the tails of the reptiles that land on them, biting their backs at the same time. The winged dragons spread their tails in a double spiral, the stippling on their bodies mimicking the scaly skin of the reptiles.

Their feline faces have anthropomorphic features that can be seen in their eyes and cheekbones.

The symbolism of the lion opens indistinctly to the realm of good and evil. In the Epistle of Peter, it is the devil. However, at the same time it is repeatedly symbolic of Christ, from Genesis to Revelation.

According to the Physiologus, the Christian naturalist and symbolist, the lion slept with its eyes open in an attitude of permanent vigilance, with this behaviour serving as the basis of its goodness in the monastic ideal. If the lion sleeps with his eyes open to keep his guard, the monk, asleep to the world, must be vigilant and attentive to divine contemplation.

At the opposite extreme, other Christian authors look to the lion for a moral lesson about sin.

Fathers and theologians unanimously identified the dragon with the old enemy of man – Satan, who in his arrogance claims to be the equal to God and incites man to worship him. In the image of the dragon, they find the life of sin and the pains of hell in a tangible way.

This antagonism between lion and dragon thus becomes an implicit message in the monk’s asceticism – in short, it is the struggle between the capacity to do good and submission to moral corruption. The righteous, with vigilance and courage, represented in the lion, can emerge victorious from this battle.

CAPTITAL 4. LIONS AND DRAGONS

Capital 5. Vultures

The vulture has its most peculiar features: a bare head down to the neck, robust, curved beaks, sometimes with a ruff, and large bodies covered with long, broad wings. The long, pointed nails of their claws perfect the image. They attach and oppose their heads in order to peck at each other’s wings.

In Ancient Egypt, the vulture symbolises the mother-goddess of the sky and the naturalists of Antiquity, evoking the myth, recreate a bird, unrelated to the male, always female, which reproduces, without sexuality, thanks to the wind. The Christianised fable places the vulture on the “eutocia stone”, originally from India, to avoid the pain of childbirth. Virginity emerges in the form of the bird: it is Mary. Meanwhile, the “eutocia stone” represents Christ.

CAPITAL 5. VULTURES

Capital 6. Lions entangled in stalks

Here, the lions are entangled in a tangle of stems. Their heads are adapted to the characteristics of the animal and from the jaw, the manes take possession of necks and chests which also continue onto the haunches and loins. The lions raise and support their forelegs on their own tails, which emerge between their lower limbs, gripping the plant with their teeth.

This framework, made up of stems and small palmettes, is modelled in the form of undulations and loops and envelops, above all, the upper part of the quadrupeds.

Already in the field of allegory, it is necessary to play with the ambivalence of the animal.

If this were the sinful lion, the intertwined circles around its head would evoke the bonds of sin and its punishment. Nevertheless, if the lion conveys the attitude of strength and vigilance necessary for the good Christian, the wild beasts in this case would dominate the stalks with the power of their jaws and indicate that the harassment of sin can be neutralised with lion-like strength.

CAPITAL 6. LIONS ENTANGLED STALKS

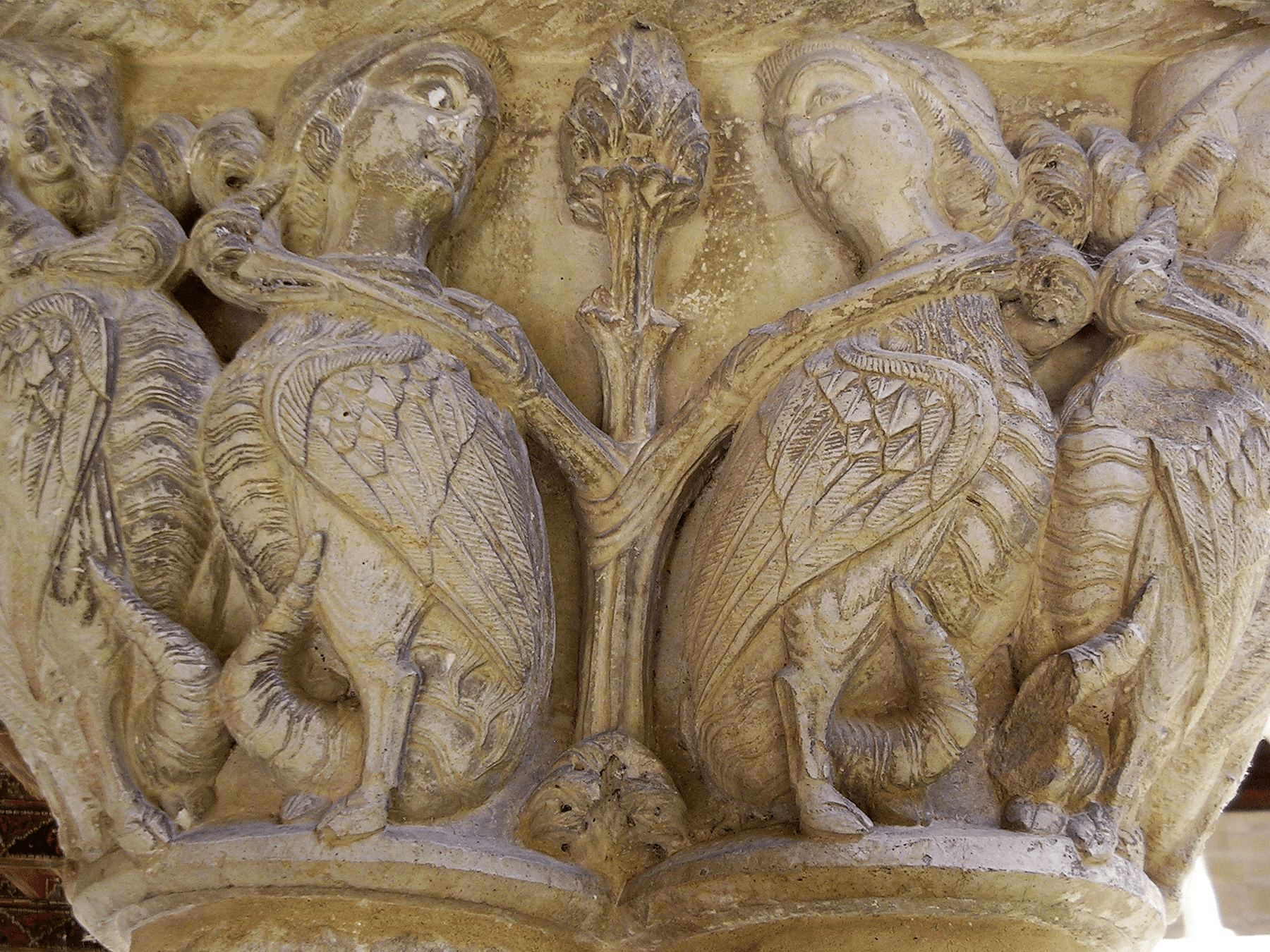

Capital 7. Lion-headed eagles

The lion-headed eagles are shown arranged two by two, and while opposing their bodies, they face each other’s heads with a forced twist of their necks. The wings, with their large span, are common to raptors, and from the necks, dense manes announce the feline’s head, particularly defined by its long hair and jaws.

Its origin is in Akkadian mythology where it embodies an evil bird called “Anzu”, a storm god with a saw-like beak, a lion’s head and an eagle’s body and talons. With the exception of its beak, it corresponds to the image of the Silos capital. However, the process of Christianisation of this Akkadian deity is obscure.

In the eagle, as in almost all symbols, there is an ambivalence of meanings to be contemplated. Its ascent brings us closer to the realm of the divine, while its descent, on the contrary, brings us closer to the earthly and involves the attraction of the material world.

Without forgetting its powerful elevation, priests and theologians alike notice how it falls to the ground, with extreme speed, driven by the need for food. They therefore found it easy to incarnate in the eagle the sin of gluttony – disastrous, in their opinion, when it hovered over the monk’s conduct.

At the same time and as a counterpoint, the elevation of its flight serves as a stimulus to break the bonds with the earthly and to rise towards God while possessing the ability to look directly at the sun, without blinking, as the righteous are supposedly able to do when contemplating divinity.

The lion, with its own ambivalence, adds to the negative image of the eagle a generic concept of evil that entails perversion for its own sake. At the opposite, positive pole, it is his courage and above all his vigilance not to cease in the search for God that add up to and are fully integrated in the divine contemplation embodied in the eagle.

CAPITAL 7. LION-HEADED EAGLES

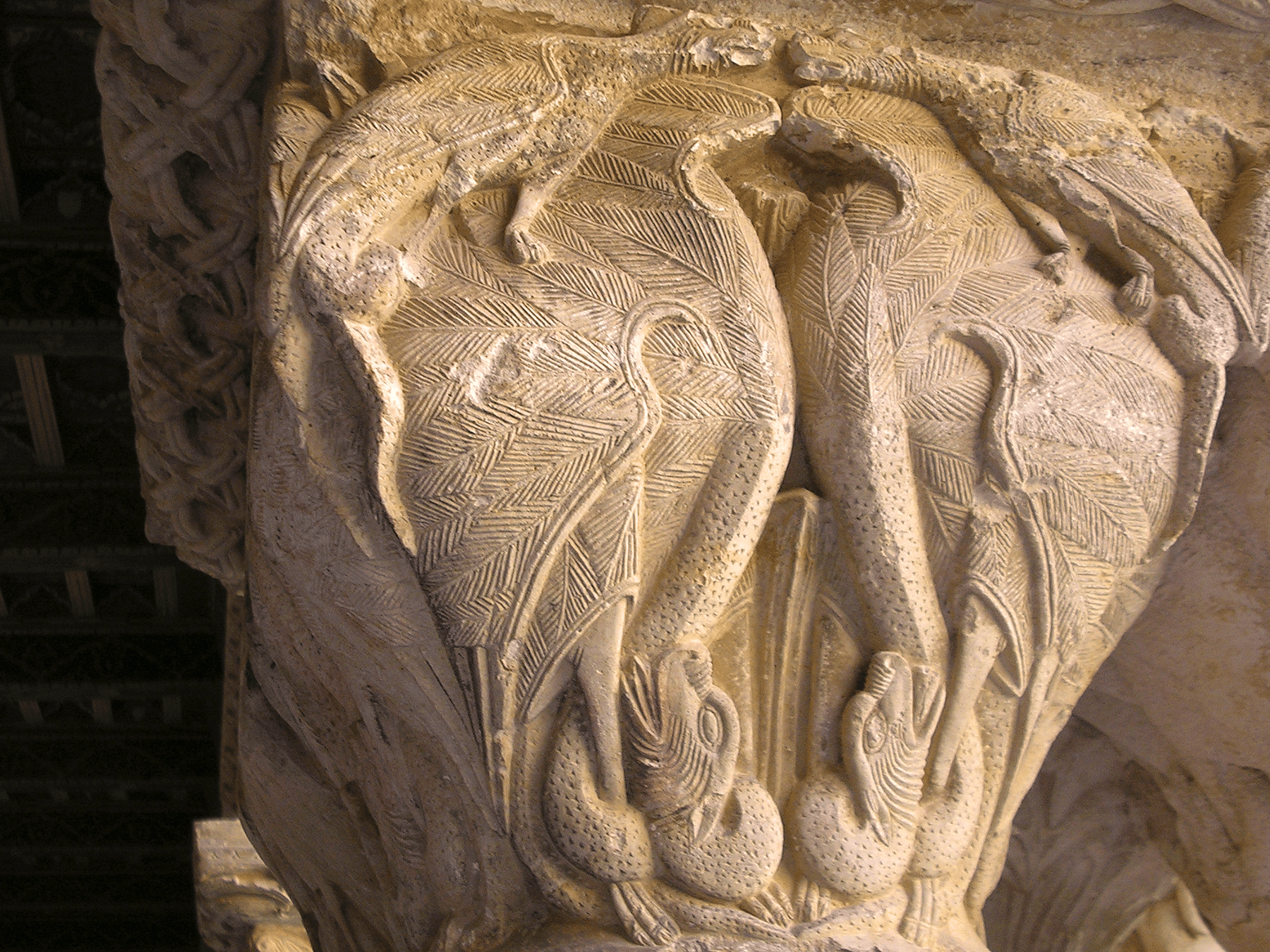

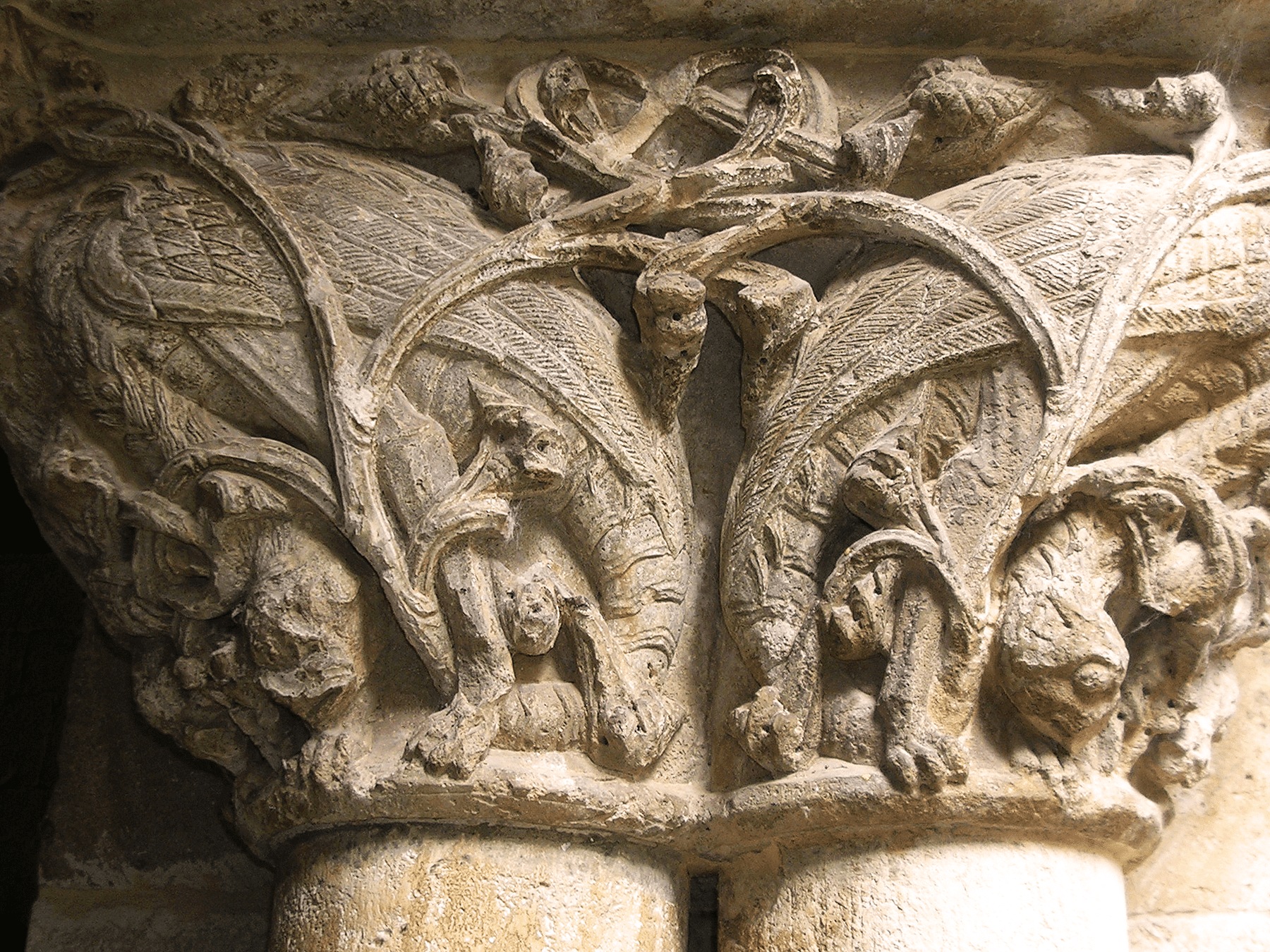

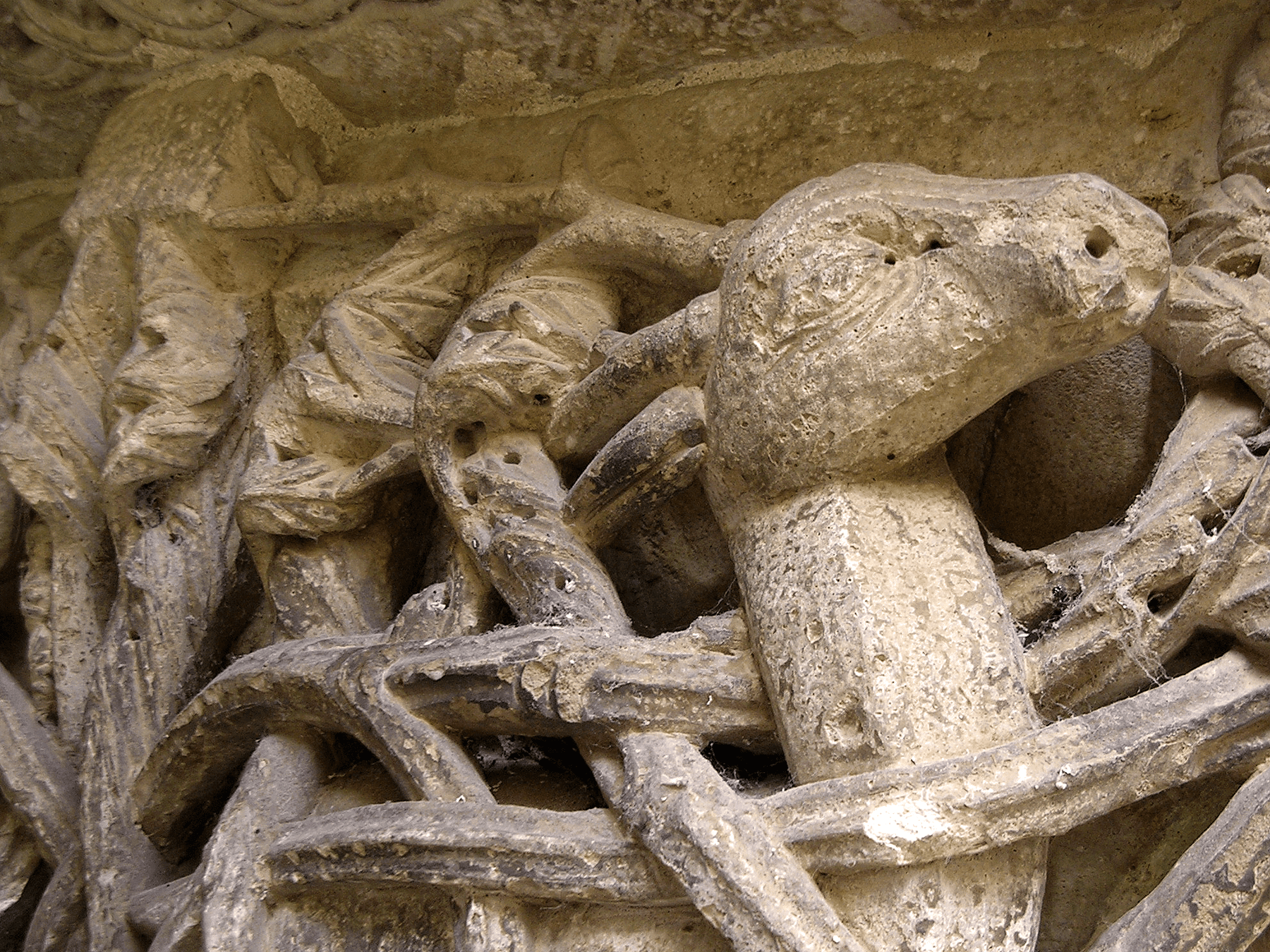

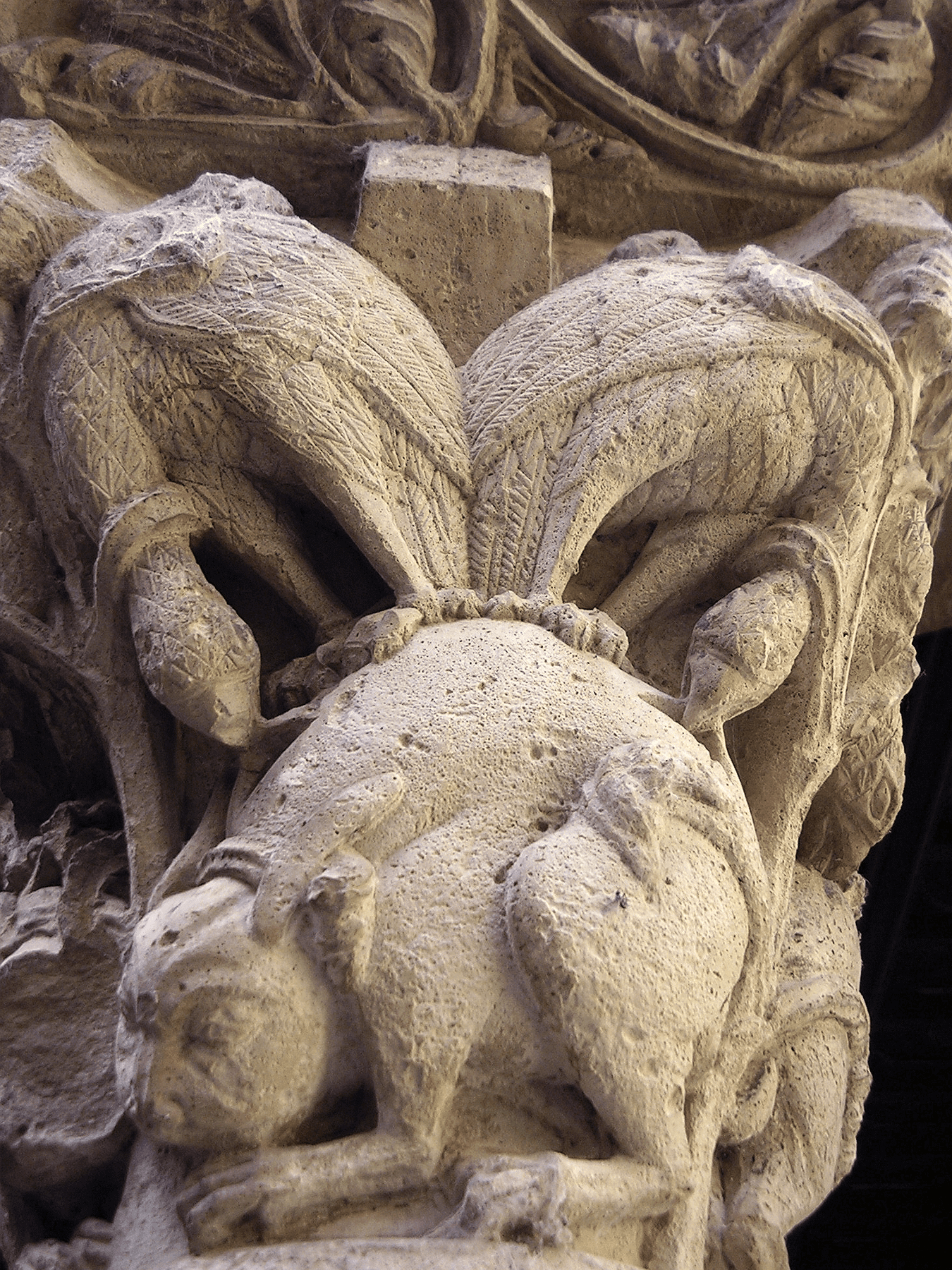

Capital 8. Bird-dragons

The fifth capital, the centrepiece of the eastern wing of the cloister, displays the theme of the dragon through two superimposed and different types of reptiles.

The lower dragon is a hybrid formed by a bird body, of enormous size, with the head, neck and tail of a reptile – in short, a bird-dragon. The wingspan and its great corpulence evoke a large bird of prey, while the extremely long neck descends, curls around one of its legs and projects its head upwards in a sort of meander. Its claws meanwhile trample the snake tail that appears between the hind feathers.

The stippling on the tail and neck resembles the skin of a reptile while the face reflects its fierceness through powerful jaws with large tongues.

Above them, on their backs are smaller, more conventional dragons, also winged, similar to those that harass the lions in capital 4. Here, its tail curls up before dropping onto the wings of the bird-dragons.

The capital is apparently centred on the figure of the dragon, the paradigm of Satan. However, only the small, superimposed reptile comes close to the infernal beast that epitomised all vice. Meanwhile, in the case of the lower dragon-bird, the imposing bird body modifies the symbol and suggests, in the light of theological interpretations, a shift towards the ethereal, close to the divine.

In its ambivalence, the figure of this dragon-bird therefore reflects man’s inner struggle between matter (the crawling characters of the bird’s face, neck and tail) and spirit (its body). Nonetheless, the formal dominance of the bird over the reptile seems to insist more insistently on the triumph of grace over the demonic stamp of the little dragons. The dragon-bird conceals an invitation to hope.

CAPITAL 8. BIRD-DRAGONS

Capital 9. Vultures

The vulture has its most peculiar features: a bare head down to the neck, robust, curved beaks, sometimes with a ruff, and large bodies covered with long, broad wings. The long, pointed nails of their claws perfect the image. They attach and oppose their heads in order to peck at each other’s wings.

In Ancient Egypt, the vulture symbolises the mother-goddess of the sky and the naturalists of Antiquity, evoking the myth, recreate a bird, unrelated to the male, always female, which reproduces, without sexuality, thanks to the wind. The Christianised fable places the vulture on the “eutocia stone”, originally from India, to avoid the pain of childbirth. Virginity emerges in the form of the bird: it is Mary. Meanwhile, the “eutocia stone” represents Christ.

CAPITAL 5. VULTURES

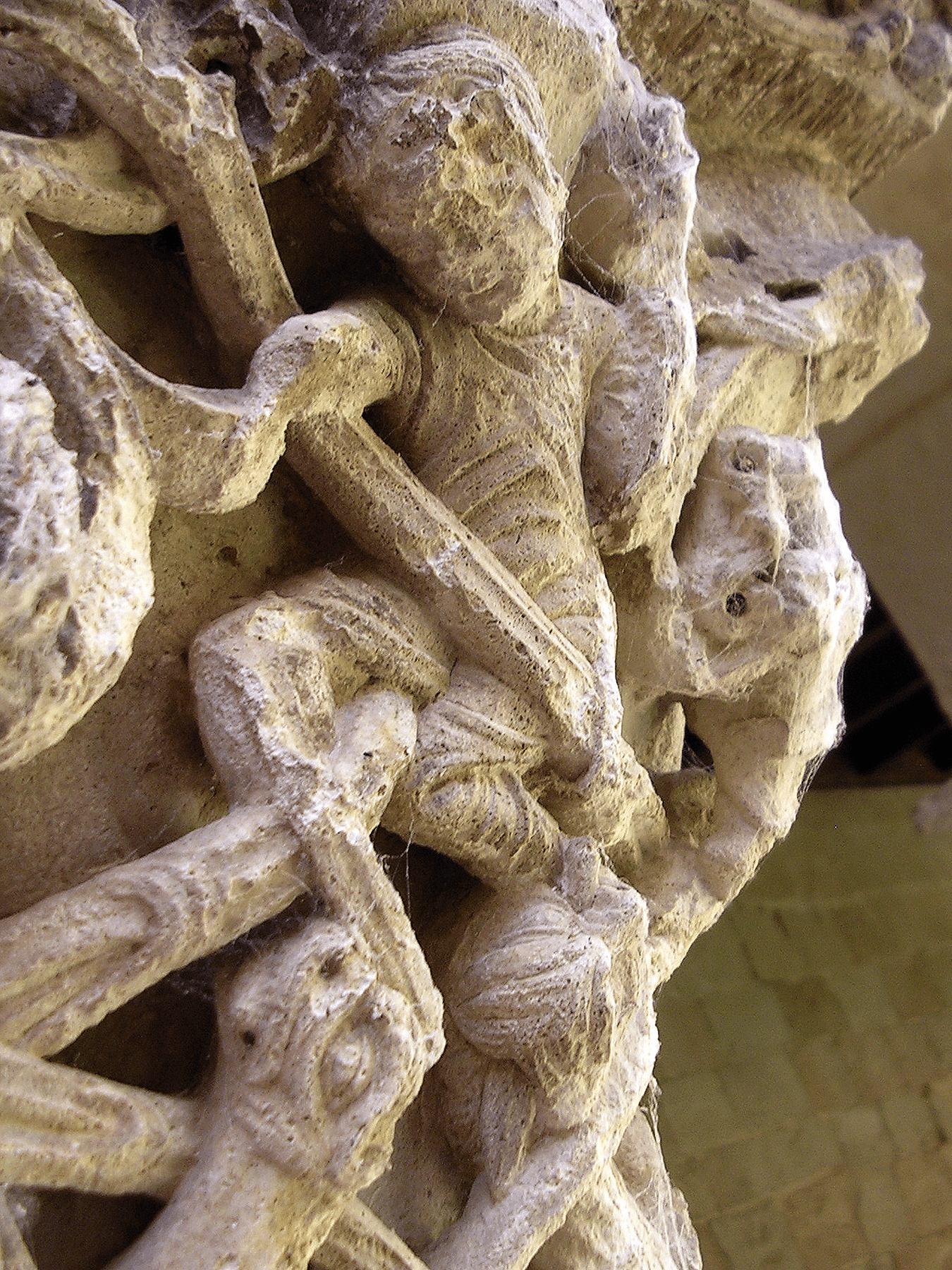

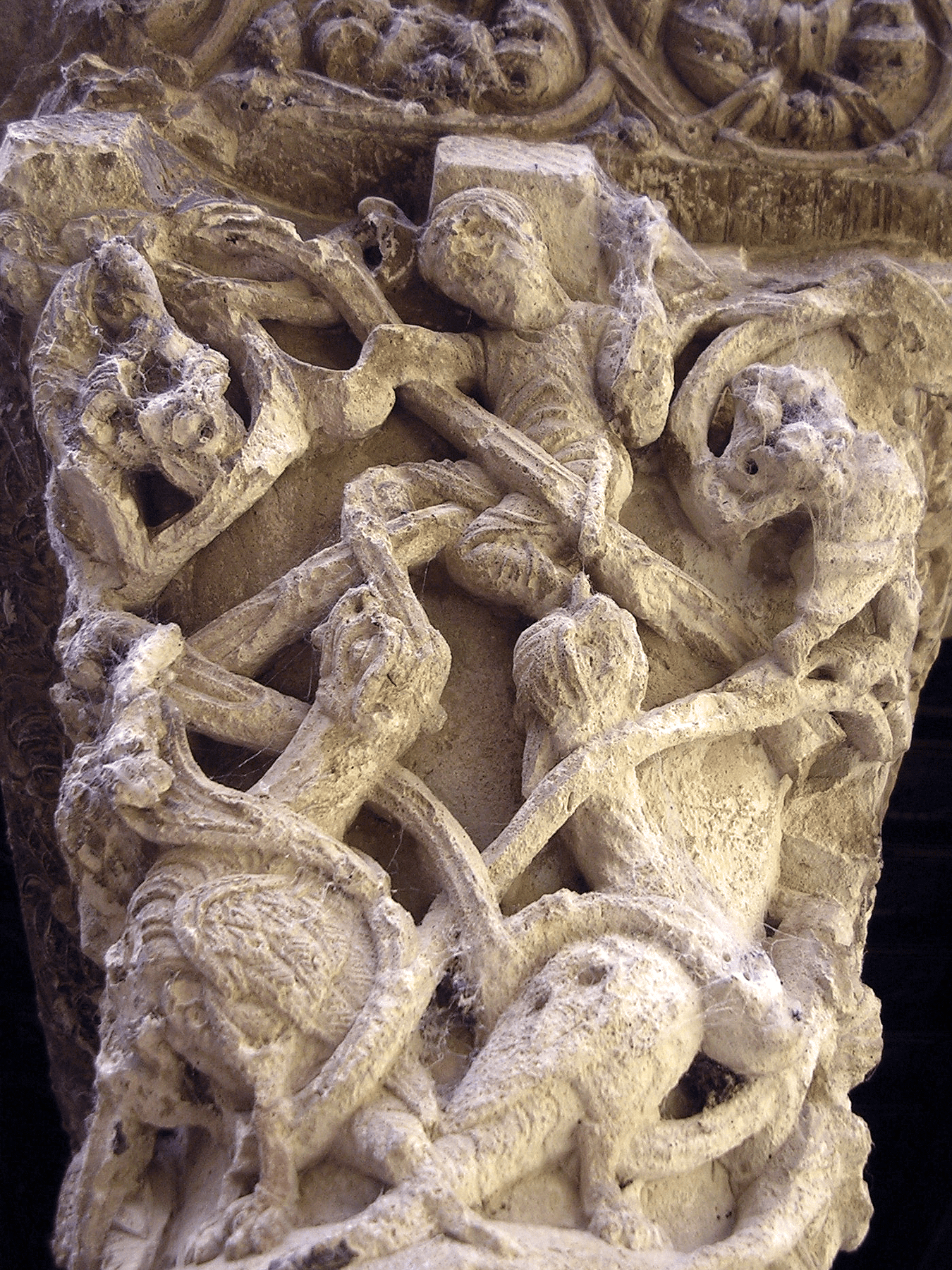

Capital 10. Men riding goats

This capital depicts naked men, mounted on goats, attacking each other with axes.

Despite the coarseness of the carving, their bodies show the tension of the struggle through their raised arms, menacingly brandishing their weapons. The opponents appear in pairs, facing each other, while paradoxically their mounts with their seemingly bleating heads are facing in the opposite direction to the fight.

The animal’s anatomy shows unmistakable signs of its identity: wool, straight horns and udders, although the wings on its sides and long tails, inserted between its legs, are unworthy of its nature.

The symbolic duality of the goat oscillates between the most degrading vices that focus on lust and the redemptive hope, embodied in Christ himself. At Silos, the naked bodies of the horsemen intensify their lasciviousness. In counterpoint, the goat is the propitiatory victim of the holocausts for the sins committed, a circumstance that inevitably makes it similar to Christ the Redeemer.

At first sight, the goats seem to drag man on their backs, towards the vices of the flesh. However, they turn their backs on the fight, with the upward direction of their heads added to their essentially climbing wings, either pointing “upwards” or bleating furiously at the aberrant attitude of the horsemen.

In one way or another, this behaviour responds better to the analogy with Christ than to the idea of salaciousness. This representation of the capital is understandable: the combatants personify lust, while the goats, on the one hand, signify this framework of lasciviousness and, on the other represent through their wings and raised necks the image of the Saviour helping man to turn away from desire

CAPITAL 10. MEN RIDING GOATS

Capital 11. Male goats

In the adjoining capital, the goats share and deepen the passion of the females through their fertility, a reflection of an overpowering sexuality. They exhibit only their countenance and legs, while the body takes on the form of a bird in a strange and fabulous symbiosis, similar to that of the dragon-bird. The heads of the goats, descending towards the collar, clearly outline their hanging beards, rugged horns and hooves, typical of male ungulates. Meanwhile, thick, knotted reptilian tails emerge from behind the wings, snaking between the legs and ending up bitten by the bearded goats.

The cursed image of the lustful goat is accentuated, if possible, by the snake’s tail, Thanks to its symbiosis with the bird, it reveals a positive and hopeful being. The reptilian tails, in their potential for vileness, are nullified by the knot and the animal’s own bite, while the bird’s body invites man to renounce his carnal bonds in favour of a desire for elevation, worthy of attaining fulfilment.

CAPITAL 11. MALE GOATS

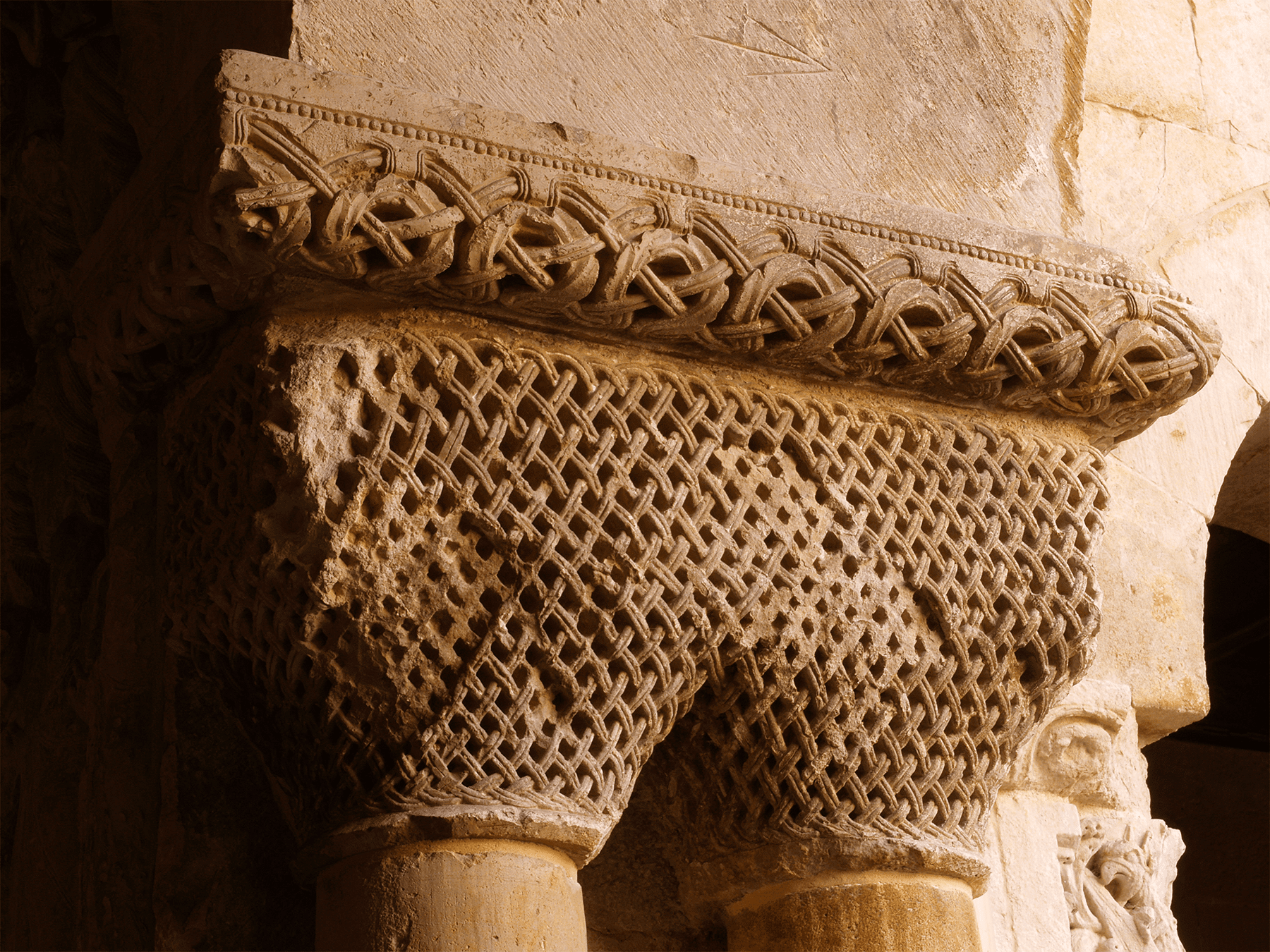

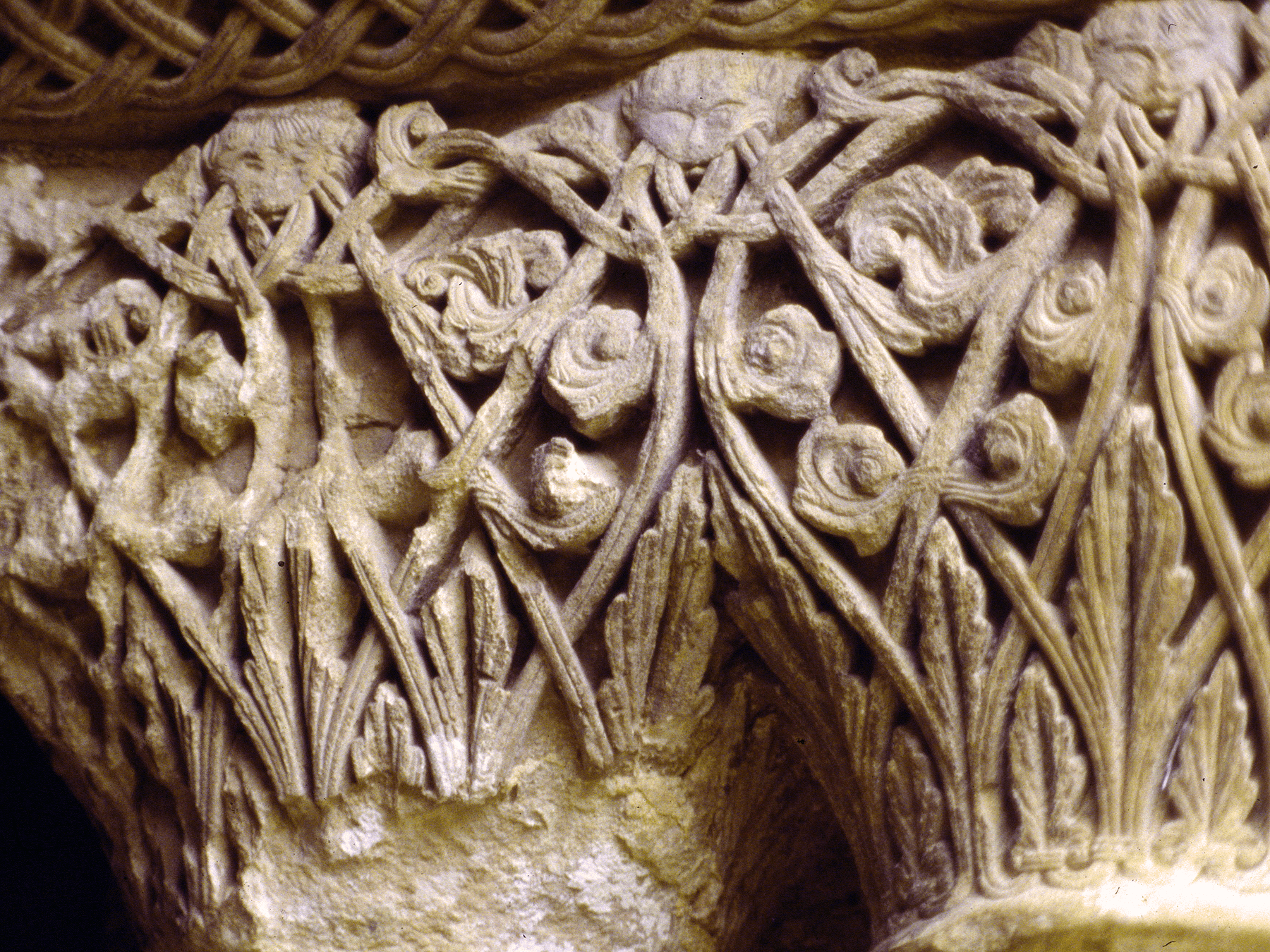

Capital 12. Intertwined stems

The plant theme of the cloister begins with capitals of intertwined stems that expand and twist around palmettes growing from an initial bud. The stems, in turn, arise from pinnate, scalloped leaves, perched on the talus, of different sizes, although at the same time they spring from the jaws of gargoyles attached to the abacus.

The tangled, intertwining plants are a new version of the bonds of sin. However, the masks, due to their magical defending character, would be the longed-for liberation from such a heavy burden.

CAPITAL 12. INTERTWINED STEMS

Capital 13. Lions entangled in stalks

Here, the lions are entangled in a tangle of stems. Their heads are adapted to the characteristics of the animal and from the jaw, the manes take possession of necks and chests which also continue onto the haunches and loins. The lions raise and support their forelegs on their own tails, which emerge between their lower limbs, gripping the plant with their teeth.

This framework, made up of stems and small palmettes, is modelled in the form of undulations and loops and envelops, above all, the upper part of the quadrupeds.

Already in the field of allegory, it is necessary to play with the ambivalence of the animal.

If this were the sinful lion, the intertwined circles around its head would evoke the bonds of sin and its punishment. Nevertheless, if the lion conveys the attitude of strength and vigilance necessary for the good Christian, the wild beasts in this case would dominate the stalks with the power of their jaws and indicate that the harassment of sin can be neutralised with lion-like strength.

CAPITAL 13. LIONS ENTANGLED STALKS

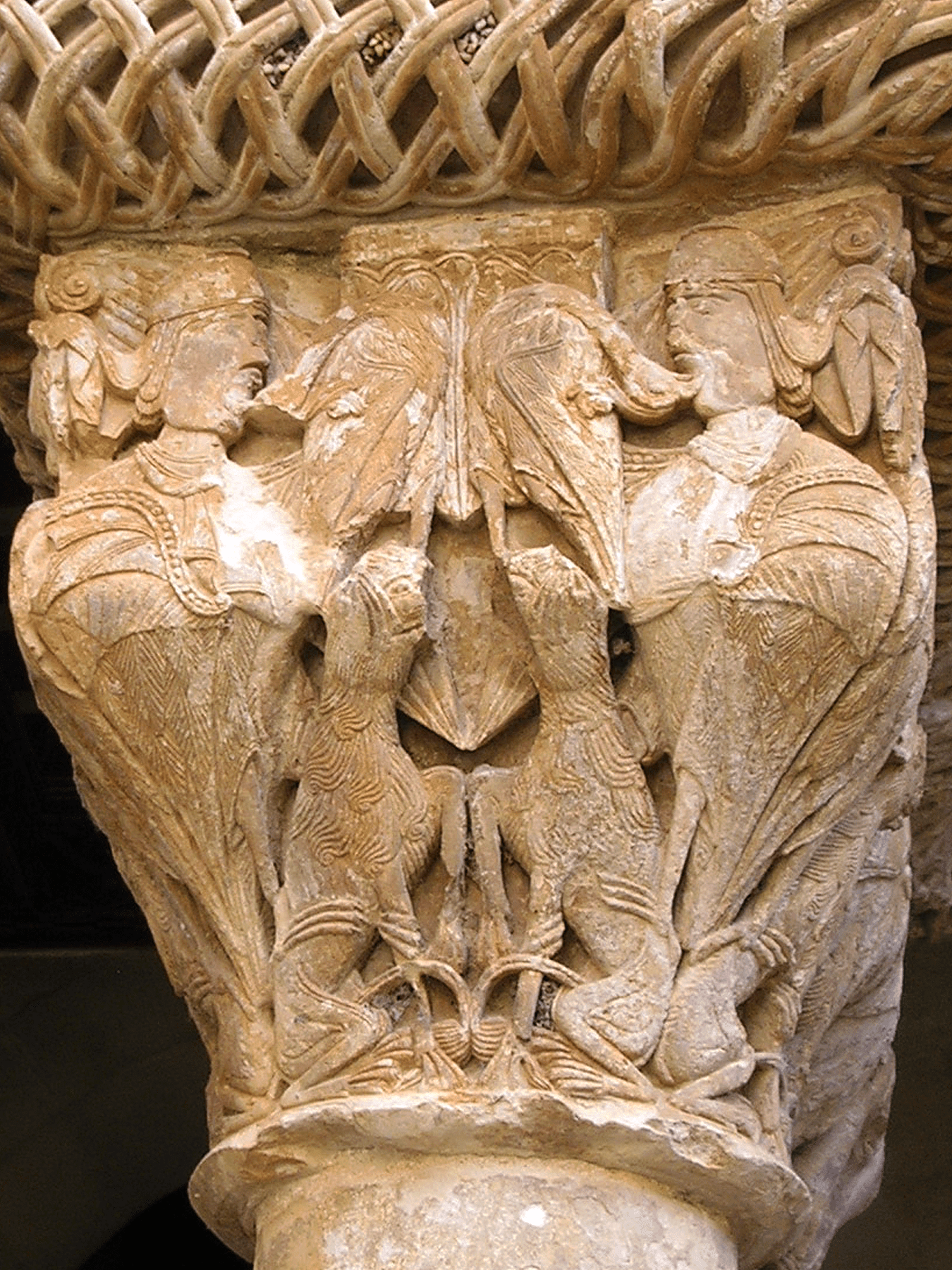

Capital 14. Mermaids, lions and phoenixes

Large bird mermaids, with the heads of women and the bodies of birds, frame a composition with two lions facing each other, half resting on the talus bone and two phoenixes perched on their heads. The mermaids sit on the backs of the lions while apart from resting on the heads of the felines, the phoenixes violently twist their necks to bite the mouths of the sirens. On an unexpected note, the lions have human faces.

The fame of the mermaids comes from Homer’s Odyssey, where they are placed them on the Island of the Sirens, singing their beautiful songs to attract and kill sailors. Without describing his appearance, Homer suggests a female being, extremely dangerous, the germ of a malevolent image linked to women’s seductive nature. In the 11th and 12th centuries, they were shown in the form of a bird with a female head, as they appear in the monastery capital.

In the minds of theologians, the Homeric song of the siren, close to the attractions of the flesh took hold, while the nymph became the metaphor of sensuality, skilled in dragging man down the path of sin. Embellished in the Silos capital with manes, head coverings and capes, they announce the soul’s doom if, through weakness or fickleness, the monk finds himself defenceless before the deceitfulness of bodily beauty.

The lions have anthropomorphic features, chiselled on their jaws when they are swallowed or regurgitated. This plastic ambiguity could embody the Egyptian “myth of the gobbling monster”, a lion which simultaneously devours and vomits out the regenerated man, ready for a new life. In Christian terms it would be the reward for a firm and vigilant attitude in the face of evil, similar to that of the lion.

The birds in the upper part reveal their identity through the crest that covers their heads, of vegetal design in Silos. In Pliny’s Natural History it corresponds to the phoenix – a bird native to Arabia whose beautifully coloured feathers are adorned with a “crest of feathers” on its head. According to legend, the bird burns itself in the fire when it senses its death and is reborn from its own ashes. In the patristic view therefore, the myth is linked to the immortality of the soul while illustrating the death and resurrection of Christ.

It is very significant that in the capital of the cloister, with the forced twisting of their necks, they peck and invalidate the mouths of the mermaids as the place from which doom arises.

CAPITAL 14. MERMAIDS, LIONS AND PHOENIXES

Capital 15. Pelicans

Pelicans intertwine their long, slender necks to peck each other’s thighs. The bird’s appearance, its claws topped with nails and its thick, curved beaks, are reminiscent of a bird of prey. This is clearly not a real pelican, but in the art of the High and Early Middle Ages it appears in the form of a bird of prey.

According to ancient naturalists, pelicans, after seeing their young die, would tear their bodies apart so that the dripping blood would bring the chicks back to life. Here, in Silos, the thighs are, in fact, the target, with the Christianised story of the pelican – an allegory of Christ: He also shed His blood on the cross so that man could be brought back to life through the remission of sins.

“I became like the pelican in the wilderness”. It is the cry of a man in solitude who, in Psalms, implores Yahweh. The monk in the monastery, far from the worldly, is similarly likened to the pelican in the wilderness. Both are the image of the loner.

CAPITAL 15. PELICANS

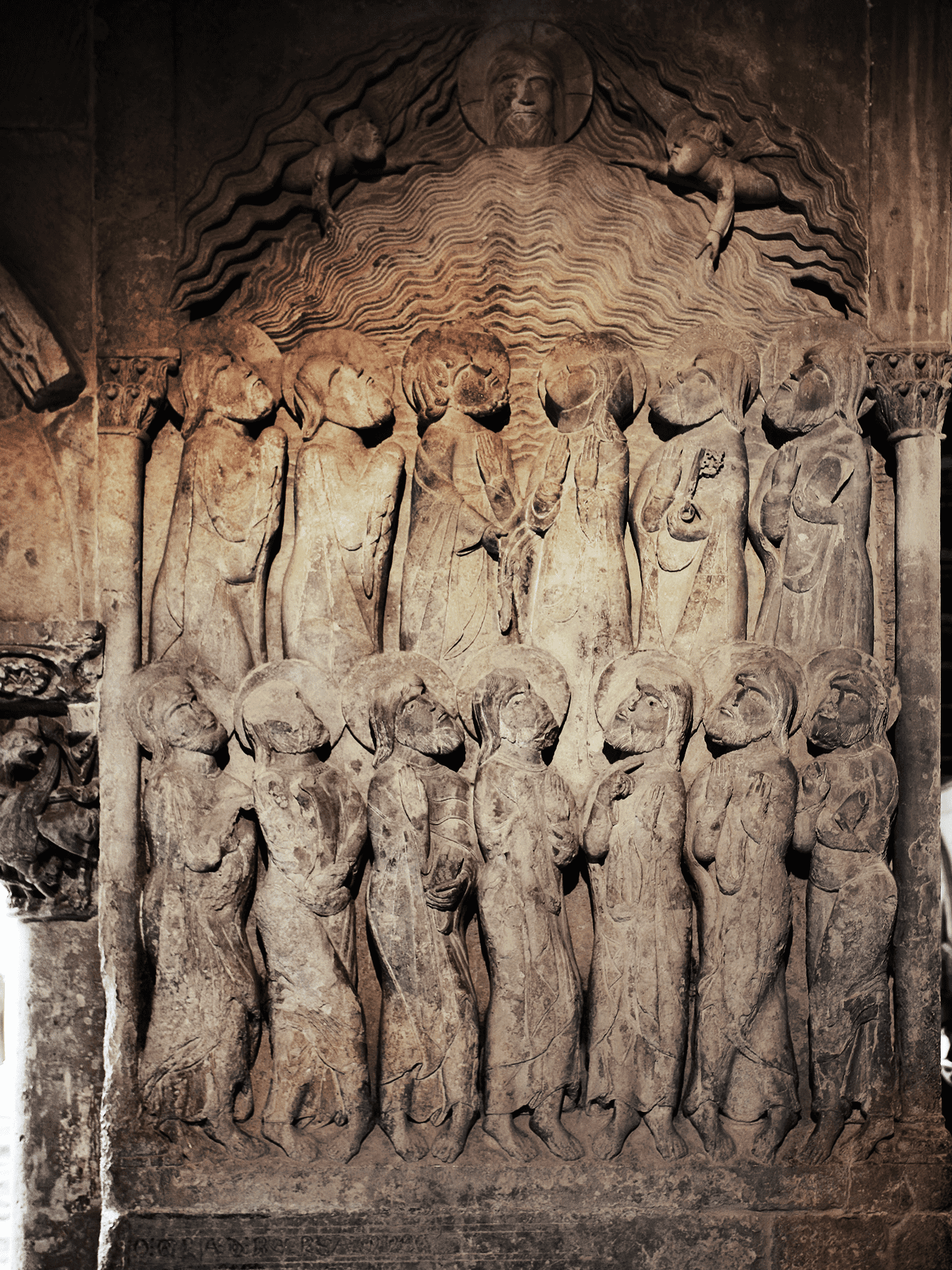

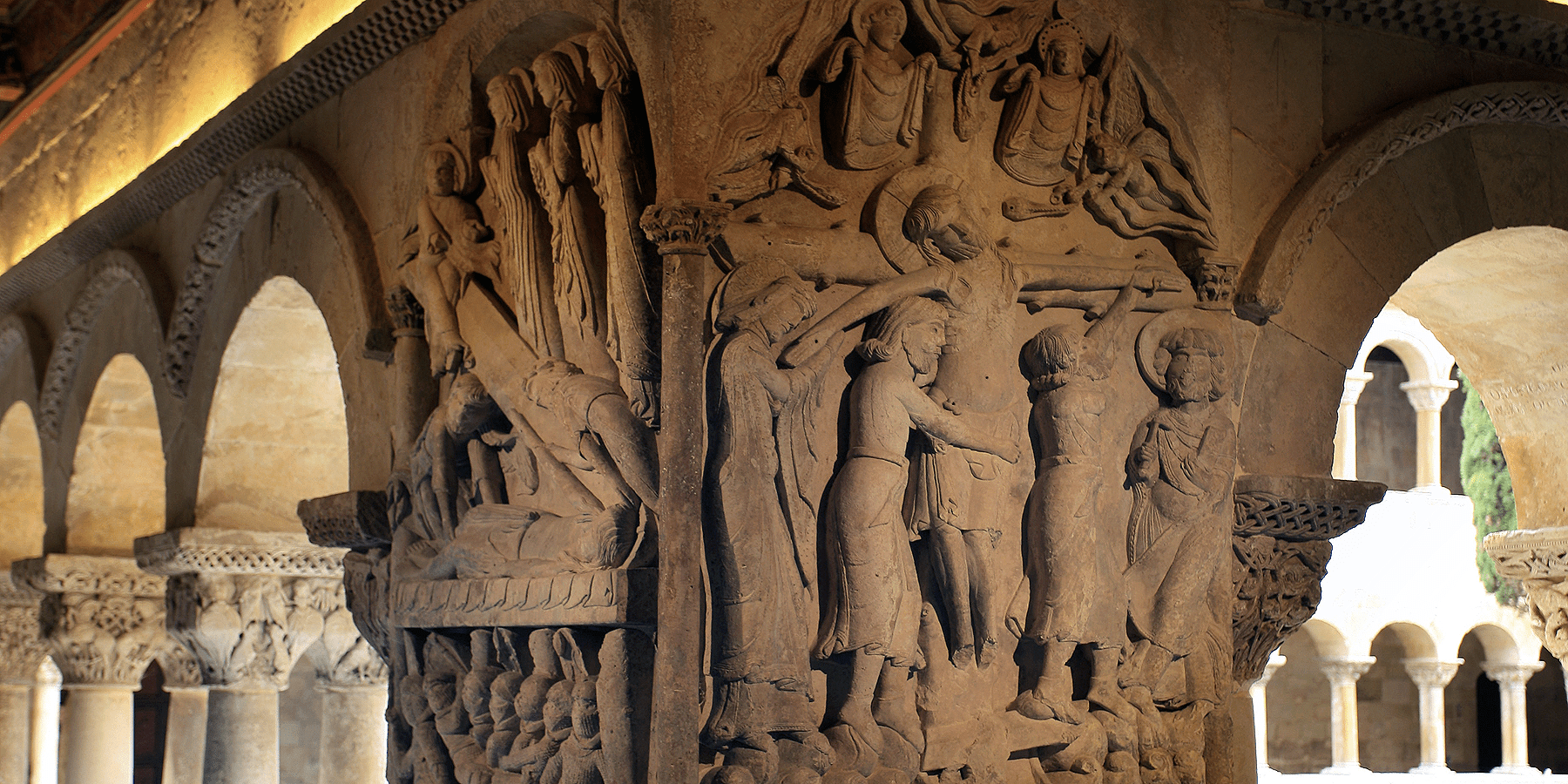

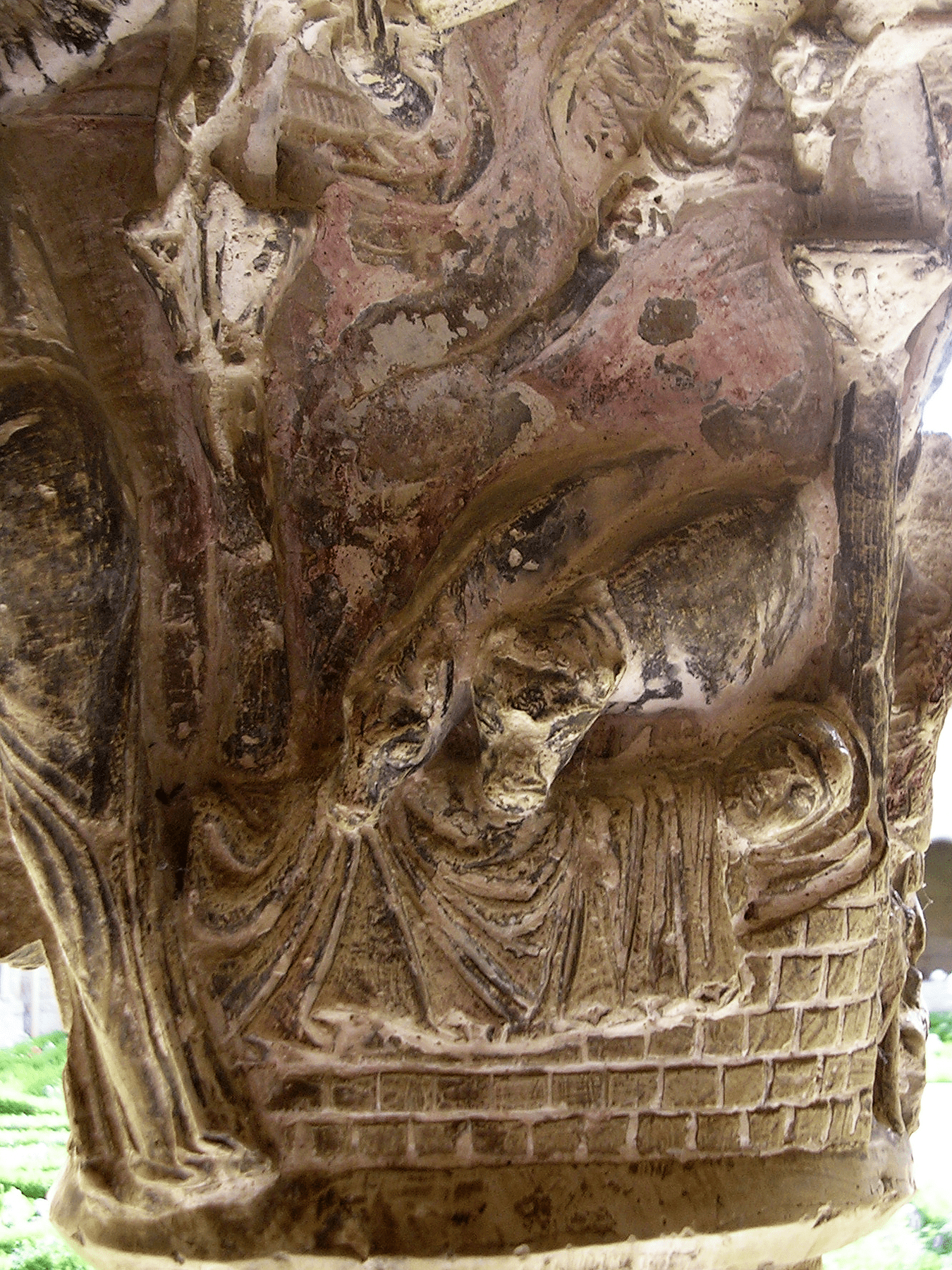

Burial and resurrection. The story continues, in the centre of the adjacent relief, with the burial of Christ. Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus lay his body on a tombstone covered with a linen cloth. A diagonal lid, forming an angle with the slab, is a half-open sarcophagus; it frames the burial scene and defines, together with the slab, two spaces, above and below, dedicated to the resurrection.

The three Marys and the angel occupy the upper part: they represent their arrival at the tomb and the heavenly message announcing the Resurrection of the Lord. In all the figures, the hands, despite their deterioration, reflect dialogue and restrained emotions. The angel points to the empty tomb, subtly suggested by the half-open stone, where the divine emissary sits. In unison, the women question and express their astonishment with their left hands, while their right hands, veiled in respect, would hold the perfumes intended to anoint the body of the Lord.

Beneath the tombstone, the soldiers of Pilate’s guard emerge, dazzled, almost numb. They are dressed in 11th century warrior’s garb, their paralysed attitude in the presence of the angel – “they stood there as if dead” – literally corresponding to the account given in Matthew’s Gospel.

RELIEFS ON THE NORTH-EASTERN PILASTER: DESCENT, BURIAL AND RESURRECTION OF CHRIST

Capital 17. Crows, lions and caladrius

In this capital, crows, lions and caladrius (a symbolic bird with healing powers and capable of predicting the fate of a sick person) weave together a new group of animals. The crows, perched on the talus bone, try to free themselves from the weight of the lions mounted atop them by grabbing their backs with their beaks. With a devouring gesture, the lions imprison the legs of other birds in their jaws, on this occasion caladrius, placed on top of them on the top of the capital – legs which are resting on the heads of the crows. Finally, the caladrius bend their dragon heads to bite the necks of the lions. Vultures in the lower corners are pecking at each other’s eyes.

The corvid reflects the most characteristic features of the crow: a robust, curved beak, especially at the tip, a rather short tail and thigh feathers. The Roman naturalist Aelian states that this bird maintains its mate for life with love and fidelity and that when one partner dies, the other remains a widow or widower.

This beautiful story had a wide repercussion in the Christian interpretation which, like the crow, sustains monastic life in the union and fidelity between Christ and the Church, represented in the group of monks and, in a special way, by the figure of the abbots.

A new type of bird appears at the top of the capital: the caladrius. Its antecedent is to be found in the royal plover, in the form of the Greek caladrius, whose alleged curative gifts attracted the attention of ancient scholars and entered the field of Christian allegory in the form of a curious fable. When faced with a mortal ailment, the caladrius looks away from the sick person; but if it perceives a passing illness, it absorbs it, flies upwards towards the sun and there burns and dissipates the illness.

The allegory is transposed to Christ himself who, like the bird, erases the faults, the passing ailments, not the irreparable ones, with his death on the cross.

In its ambivalence, the caladrius is both an image of Christ and an impure animal in the Old Testament. The same is true of the serpent, which although essentially unclean, is also a symbol of Christ, according to Exodus, with sufficient similarity to associate the two animals in the figurative arts. In the Bible, the serpent is conceived of in the form of a dragon; hence the bird, the caladrius, takes on the head of a dragon, sometimes with horns as proof of power. It is a pity that the deterioration of the capital prevents a clear view of the image of the caladrius, although the dragon’s heads, which resist the wear and tear of the stone, are what allow us to recognise the mythical bird.

Through the crow, monastic life shows its commitment, its fidelity to Christ in his role as Judge, who, like the caladrius will decide who is to live or die. The lions, with their threatening attitude, try to break links between the Church (crow) and Christ (caladrius). However, the vigilance implicit in the symbolic duality of the lion must support the triumph of loyalty to Christ. Meanwhile the vultures, standing at an angle alongside the crows, reaffirm the principle of chastity, inherent to the Church, and also implicit in the attitude of the corvid towards its mate.

CAPITAL 17. CROWS, LIONS AND CALADRIUS

Capital 18. This capital has disappeared

It represented the 24 elders of the Revelation of Saint John.

CAPITAL 18. THIS CAPITEL HAS DISAPPARED

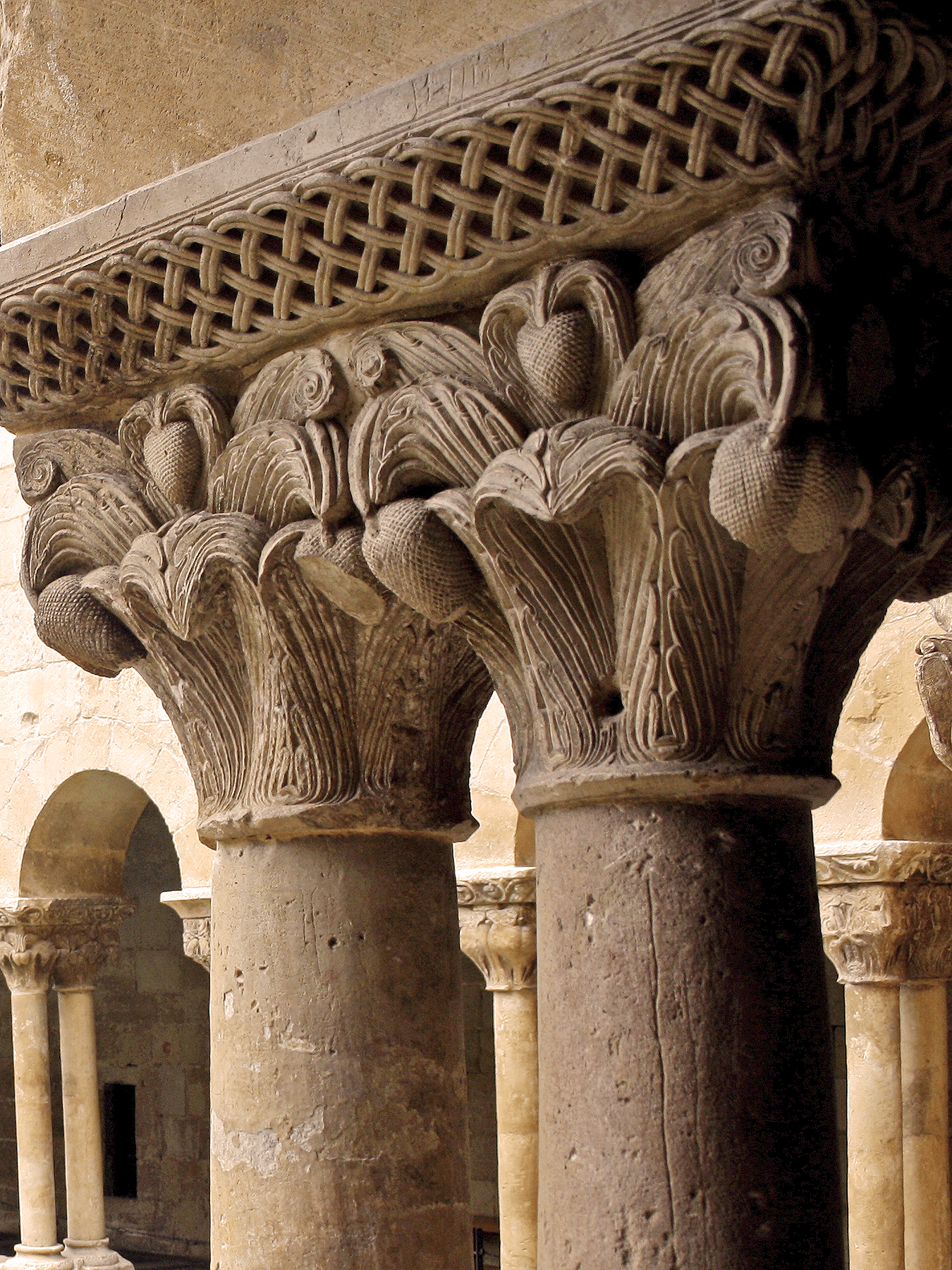

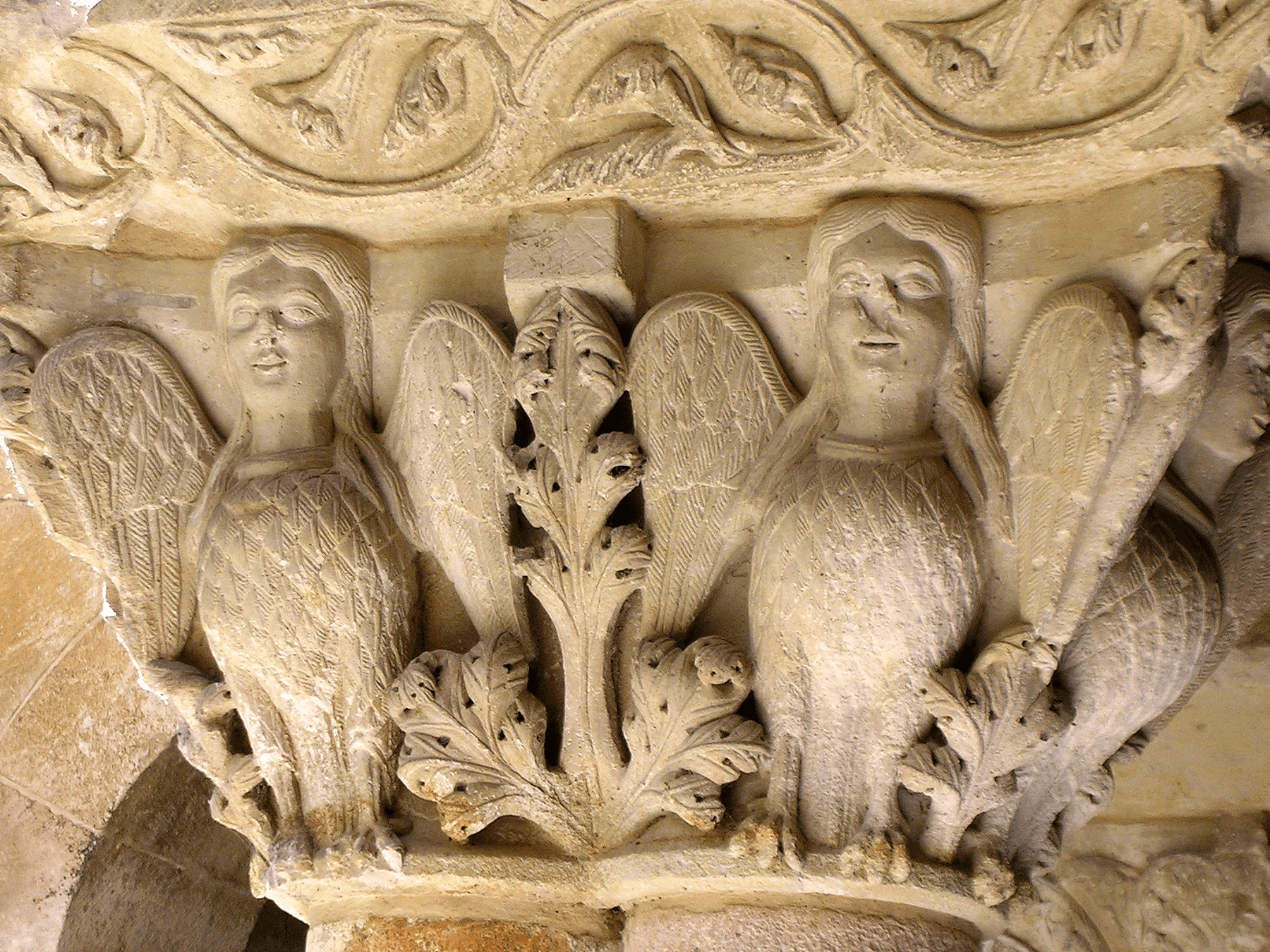

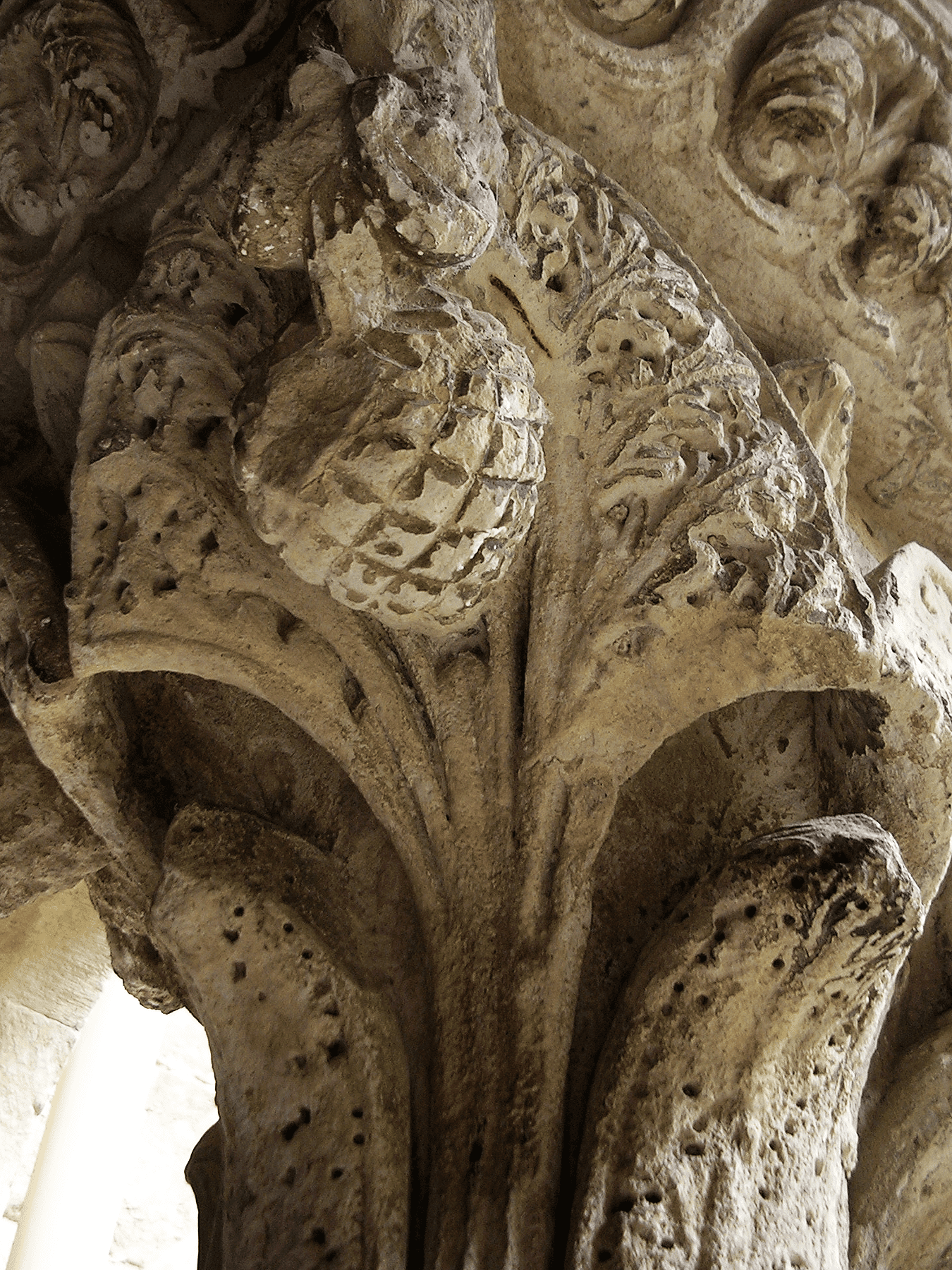

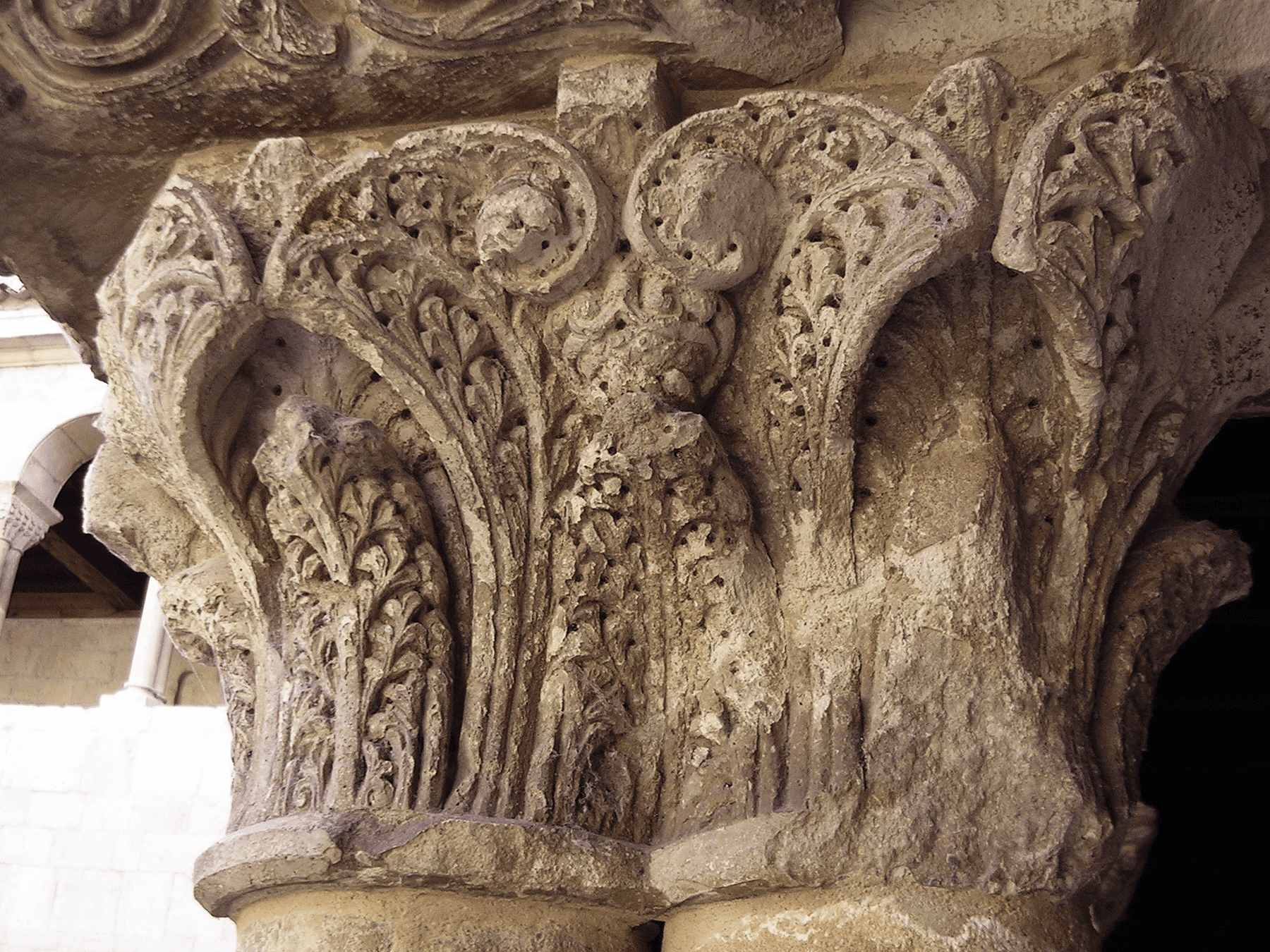

Capital 19. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 19. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 20. Mermaids and snakes

Large bird mermaids dominate the capital. Their bodies are set against each other as they turn and face each other’s heads, and the hind wings stand out against a vegetal background of thick stalks and large leaves topped by a scroll.

They correspond to the archetype of a bird’s body and a woman’s head, with unkempt hair as a sign of their impudence, perhaps accentuated by a textile ornament and a necklace around their necks. However, they also sport the horns and hooves of ungulates, such as goats, presumably to further their status as inciters of lust.

In the thinking of the monks, woman contains the poison of the serpent, pregnant with carnal vices. These mermaids, synonymous with Eve the temptress, suggest a similar idea. From their mouths and their insides, serpents emerge, with trifid tongues, which descend on their wings, an indication of the close link between the seed of temptation, the ophidian, and temptation itself, embodied in the seductive songs of the sirens.

However, the symbolic interpretation of the serpent is somewhat more complex. In memory of the “bronze serpent” of the Exodus, it unanimously becomes a prefiguration of Christ and is thus integrated into the equivalences of life and immortality. It has already been perceived in the caladrius.

However, transcending that, the knowledge of antiquity unravels characters of the serpent that can hardly be ignored in the realm of Christian allegory. As an example, the Roman naturalist Pliny refers to how the reptile, in the face of man’s attack, fiercely preserves its head, although it ends up surrendering the rest of its body to death. A model of prudence in the face of temptation therefore, since the safeguarding of the spirit (the head) prevails over the possible breakdown of the flesh (the body).

A perfect lesson for monastic life. Faced with this peculiarity, the Holy Fathers would inevitably recall Christ’s advice to his disciples: “Be wise as serpents and innocent as doves” (Matthew 10:16).

CAPITAL 20. MERMAIDS AND SNAKES

Capital 21. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 21. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 22. Eagles

The birds resemble vultures pecking at each other’s joints. However, they are golden eagles in that their necks are shorter, less streamlined, and feathers encroach on their faces. In short, the long neck and the bald head, peculiar features of the vulture, have disappeared. Above them, other birds flying in the opposite direction to the lower ones are now unrecognisable due to deterioration, precisely because of the wear on their heads.

As already mentioned, the eagle invites the memory of an unbridled appetite akin to gluttony through its rapid descent to land in search of prey. Nevertheless, through its powerful soaring to the heavens, its ambivalence also evokes the idea of elevation that brings the divine closer.

CAPITAL 22. EAGLES

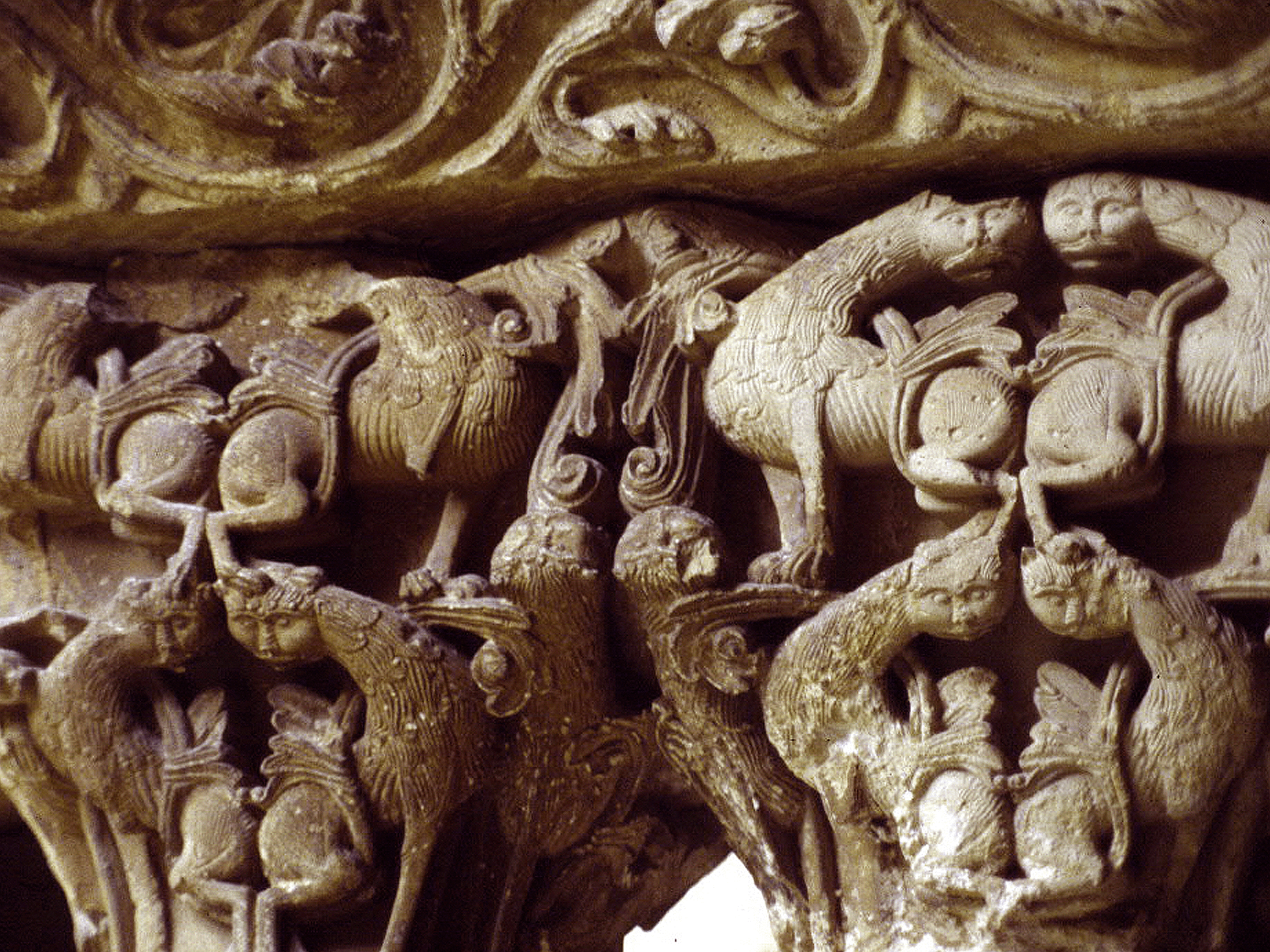

Capital 23. Mermaids and turtledoves. Lions and caladrius

In this fifth capital in the northern wing, we see two different and apparently dissociated themes: groups of mermaids and turtledoves and an intricate relief of animals, dominated by the figure of the lion, which occupies the side of the capital closest to the tomb of Domingo Manso, the future Saint Dominic of Silos.

This relief arranges the animals in three superimposed rows. In the lowest, paired lions, with affable, almost smiling faces, stand on their hind legs and hold, between their haunches, long croziers which, protruding from their bodies, rise behind their heads, curve and end in the form of a scroll next to the paws of the big cats above them. At the same time, the tails are tapering smoothly over the reverse but soon end in a grooved arch that reaches and imprisons the cane. Tiny little lion busts have been sculpted under these grooves and grasp the croziers, with hands that look more human than animal.

In the middle frieze, the figure of the lion again appears, paired, this time resting its forelegs on the staffs, while holding its hind legs on the heads of its fellow lions. Also with humanised faces, they nibble on stalks that descend to the staffs. The sequence ends with some highly stylised birds, whose bodies distribute their weight between the backs and heads of the lions in between, which they peck on the foreheads. Their serpent-shaped faces once again reveal the caladrius.

The lions with croziers in the lower row could represent Domingo Manso himself. The lion is a symbol of vigilance, a notable virtue in Saint Dominic of Silos, always attentive to the spiritual needs of his community. The staff is the emblem of the “shepherd”, the name given to the abbot in the Rule of Saint Benedict. And lastly, the small lions, sheltered in the tail and clinging to the crozier, evoke the monks, disciples and companions of Dominic, holding on to the protection and guidance of their beloved abbot.

In their symbolic duality, the lions in between depict the Saint’s struggle to discern the correct path to perfection. They therefore reflect the forces of the Evil One vanquished by the courage and inner strength of the saint, also implicit in the animal.

High above hovers the caladrius; the bird-Christ, healer and judge. It seems to attack the lion with its jaws. But it doesn’t dodge it, instead landing on the animal. He has made the selection of the sick, as legend has it, which leads him to healing, to eternal bliss. The relief ultimately shows how the monks, under the protection of their abbot, come to attain salvation.

In the remaining capitals of the ensemble, small birds perch on opposing bird-mermaids, although they turn and place their heads to face each other. The birds gag the mouths of the mermaids with their feet, but they also turn their heads to nibble the ears of a face attached to the cornice, on the central axis of the capital. These small-headed birds, with their pointed wings and rather long tails, resemble turtledoves – birds whose symbolism fits perfectly with the notion of the ideal monk.

Based on the knowledge and traditions garnered from naturalists, the turtledove’s monogamy and solitary life in the desert are emphasised. Like the crow, the bird is monogamous but differs in that it is solitary. The monks therefore highlight its condition as a chaste bird, its fondness for solitary places, with both attributes – chastity and abandonment of the world – intrinsic aspects of the pillars of monastic life. In the capital, the turtledoves, representing chastity, seal the mouths of the sirens with their legs, the very source of their seductive songs and possible source of perdition for the solitary monk. At the same time, they nibble at the ears of the sculpted faces, the place through which sounds are perceived; but these faces, bordering on the magical, announce both the existence of evil powers and the possibility of invalidating them.

The two reliefs, mermaids and lions combined in a single capital, perfectly convey the demeanour of Saint Dominic of Silos. In the solitude of his monastery, he is the righteous man, firm in the face of the temptations of the flesh and in the exercise of virtue. He is also the monk capable of leading his companions to a joyous Last Judgement.

An epigraph was engraved on the abacus, which translates as follows: “This tomb covers the remains of a man who already enjoys the divine light called Dominic, Christ’s gift to this world as a mirror of virtues. May he protect the Community that trusts in him.”

CAPITAL 23 MERMAIDS AND TURTLEDOVES. LIONS AND CALADRIUS

Capital 24. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 24. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 25. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 25. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 26. PELICANS

Pelicans intertwine their long, slender necks to peck each other’s thighs. The bird’s appearance, its claws topped with nails and its thick, curved beaks, are reminiscent of a bird of prey. This is clearly not a real pelican, but in the art of the High and Early Middle Ages it appears in the form of a bird of prey.

According to ancient naturalists, pelicans, after seeing their young die, would tear their bodies apart so that the dripping blood would bring the chicks back to life. Here, in Silos, the thighs are, in fact, the target, with the Christianised story of the pelican – an allegory of Christ: He also shed His blood on the cross so that man could be brought back to life through the remission of sins.

“I became like the pelican in the wilderness”. It is the cry of a man in solitude who, in Psalms, implores Yahweh. The monk in the monastery, far from the worldly, is similarly likened to the pelican in the wilderness. Both are the image of the loner.

CAPITAL 26. PELICANS

Capital 27. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 27. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 28. Currently non-existent

CAPITAL 28. CURRENTLY NON-EXISTENT

Capital 29. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 29. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 30. Lion-headed eagles

The lion-headed eagles are shown arranged two by two, and while opposing their bodies, they face each other’s heads with a forced twist of their necks. The wings, with their large span, are common to raptors, and from the necks, dense manes announce the feline’s head, particularly defined by its long hair and jaws.

Its origin is in Akkadian mythology where it embodies an evil bird called “Anzu”, a storm god with a saw-like beak, a lion’s head and an eagle’s body and talons. With the exception of its beak, it corresponds to the image of the Silos capital. However, the process of Christianisation of this Akkadian deity is obscure.

In the eagle, as in almost all symbols, there is an ambivalence of meanings to be contemplated. Its ascent brings us closer to the realm of the divine, while its descent, on the contrary, brings us closer to the earthly and involves the attraction of the material world.

Without forgetting its powerful elevation, priests and theologians alike notice how it falls to the ground, with extreme speed, driven by the need for food. They therefore found it easy to incarnate in the eagle the sin of gluttony – disastrous, in their opinion, when it hovered over the monk’s conduct.

At the same time and as a counterpoint, the elevation of its flight serves as a stimulus to break the bonds with the earthly and to rise towards God while possessing the ability to look directly at the sun, without blinking, as the righteous are supposedly able to do when contemplating divinity.

The lion, with its own ambivalence, adds to the negative image of the eagle a generic concept of evil that entails perversion for its own sake. At the opposite, positive pole, it is his courage and above all his vigilance not to cease in the search for God that add up to and are fully integrated in the divine contemplation embodied in the eagle.

CAPITAL 30. LION-HEADED EAGLES

Capital 31. Overlapping lions

Here the lions are the sole protagonists of the capital. They form overlapping pairs, which counterpoint their haunches and twist their necks in order to bring their heads closer together. In addition to their ornamental function, stems with palm-shaped leaves replace the tails of the lions or support the lions in the upper row.

In contrast to the fierce, roaring lion, these animals with their semi-human and peaceful faces invite us to ponder on the virtues implicit in their symbolism: courage to confront the follies of human nature and the vigilance necessary to prevent them from encouraging deviations in man’s conduct.

CAPITAL 31. OVERLAPPING LIONS

Capital 32. Eagles and phoenixes

Phoenixes perched on eagles cover the surface of this capital. In the lower part, the eagles bend their necks to peck at each other’s eyes, while the phoenixes counterbalance their bodies, turning and facing each other’s heads.

The scene combines the ascent to the divine, represented in the eagle, with the joy of Christ’s proximity and immortality embodied in the phoenix. The allegorical symbiosis of eagles and phoenixes fully justifies their fusion in this capital: they reveal the most sublime, ascension and eternity, perfectly realising the monk’s aspirations.

CAPITAL 32. EAGLES AND PHOENIXES

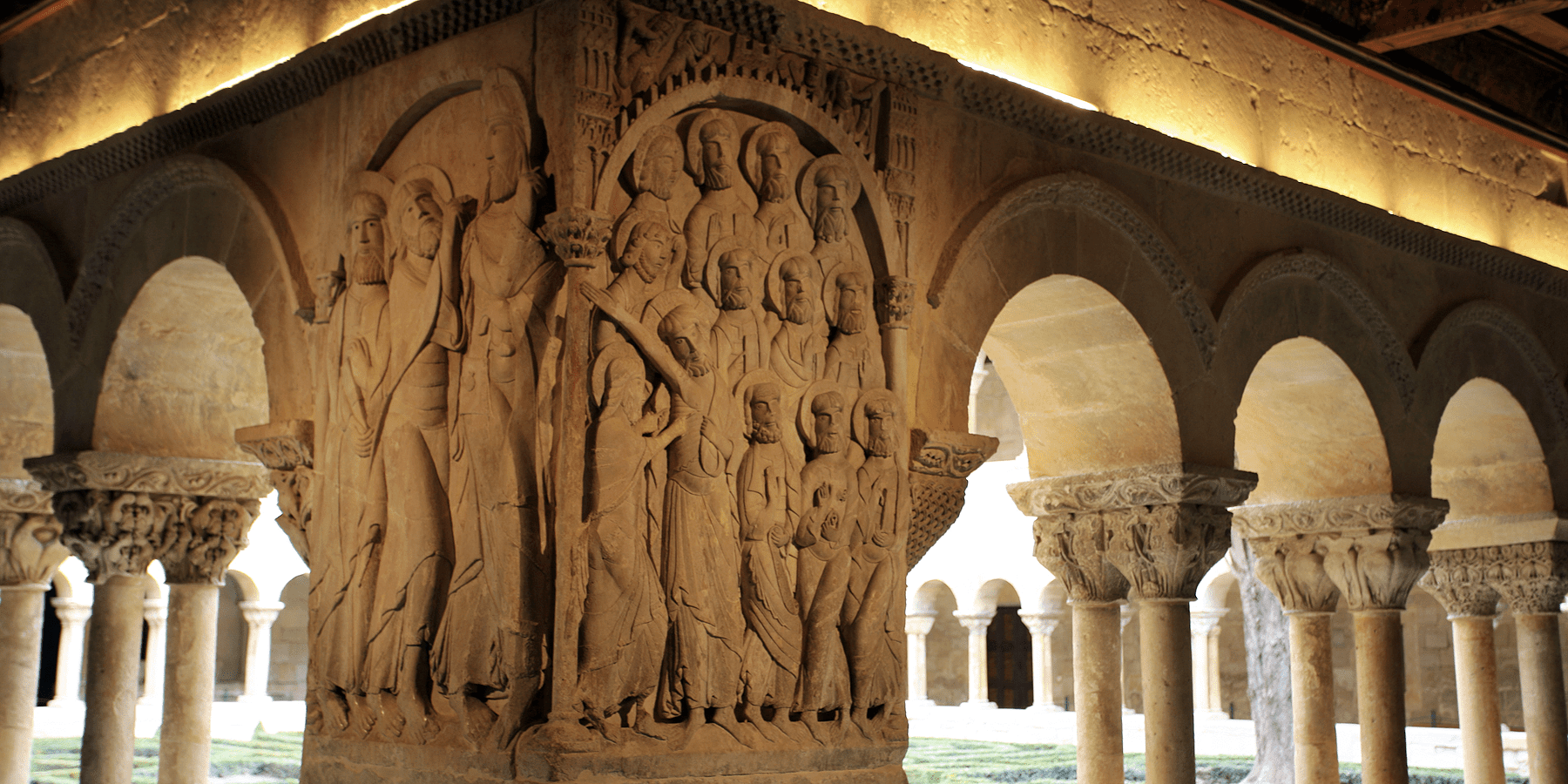

The relief on the north façade depicts the appearance of the risen Christ to two of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. It seems to capture a precise moment in history, expressed in the gesture of the disciple closest to the Lord. Perhaps the moment when, after walking together in animated chatter to the vicinity of the village, they urge Christ, apparently determined to continue the march, to stay with them as night is approaching.

Christ turns his head and listens to the disciples. In reference to the disciples’ condition of “peregrinus” and “stranger”, he carries the pilgrim’s staff and purse with the Jacobean shell, alluding to the Pilgrim’s Way to Santiago, as a distinctive feature of their sack.

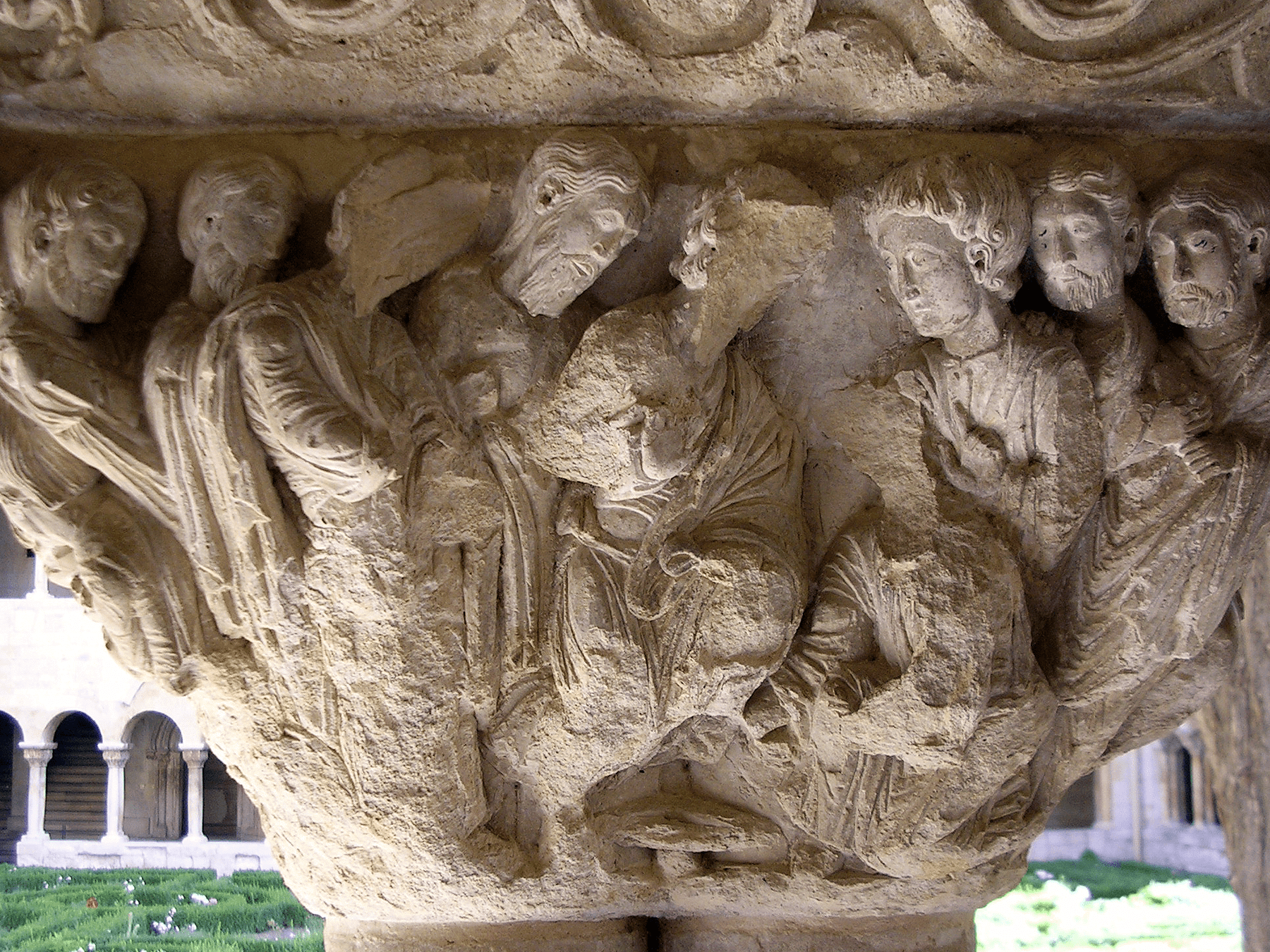

The Doubt of Saint Thomas, on the west façade of the same pilaster, closes, in the cloister of Silos, the cycle of the apparitions of the Risen Christ.

The scene revolves around Christ and Thomas, since, despite the fact that they are cornered in the composition, they attract the gaze of all the apostles who surround them and who are recognisable thanks to the inscriptions on their halos. Christ stretches out his right arm to reveal the wound in his side, while the disbelieving disciple puts his finger in the laceration to verify that Christ is indeed risen.

The presence of the Apostle Paul, a bald, rough-faced figure with a rough forehead, next to Christ is surprising. Next to him, Peter holds the key in his hand as a talking symbol. Paul was not one of the Twelve, the disciples who lived with Christ. It is therefore a historical alteration designed to highlight an idea that transcends while simultaneously complementing history: the Church, constituted by the apostolic college present in the relief, is the legacy of Christ on earth, with its universal character witnessed by the joint presence of Peter, apostle to the Jews, and Paul, apostle to the Gentiles

RELIEFS ON THE NORTHWEST PILASTER: THE DISCIPLES OF EMMAUS AND THE DOUBT OF ST THOMAS

Capital 34. PELICANS

Pelicans intertwine their long, slender necks to peck each other’s thighs. The bird’s appearance, its claws topped with nails and its thick, curved beaks, are reminiscent of a bird of prey. This is clearly not a real pelican, but in the art of the High and Early Middle Ages it appears in the form of a bird of prey.

According to ancient naturalists, pelicans, after seeing their young die, would tear their bodies apart so that the dripping blood would bring the chicks back to life. Here, in Silos, the thighs are, in fact, the target, with the Christianised story of the pelican – an allegory of Christ: He also shed His blood on the cross so that man could be brought back to life through the remission of sins.

“I became like the pelican in the wilderness”. It is the cry of a man in solitude who, in Psalms, implores Yahweh. The monk in the monastery, far from the worldly, is similarly likened to the pelican in the wilderness. Both are the image of the loner.

CAPITAL 34. PELICANS

Capital 35. VULTURES

The vulture has its most peculiar features: a bare head down to the neck, robust, curved beaks, sometimes with a ruff, and large bodies covered with long, broad wings. The long, pointed nails of their claws perfect the image. They attach and oppose their heads in order to peck at each other’s wings.

In Ancient Egypt, the vulture symbolises the mother-goddess of the sky and the naturalists of Antiquity, evoking the myth, recreate a bird, unrelated to the male, always female, which reproduces, without sexuality, thanks to the wind. The Christianised fable places the vulture on the “eutocia stone”, originally from India, to avoid the pain of childbirth. Virginity emerges in the form of the bird: it is Mary. Meanwhile, the “eutocia stone” represents Christ.

CAPITAL 35. VULTURES

Capital 36. Lions, lion cubs and eagles

This capital has a dense weave of plant stalks and animals. The stems rise out of lower trunks attached to the talus intended to house pairs of animals, which form large meanders in an upward movement. The first contains pairs of lions, the next pairs of eagles and the one closest to the abacus has paired lions.

Lions and eagles exceed the capacity of the circles and stick their heads out of their limits in order to achieve the full development of their bodies. Finally, next to the abacus, the small lions offer a strange posture, perhaps foetal in appearance.

Lower lions and central eagles, in their previously mentioned negative meaning, favour the fear of falling into vice. However, in their most sublime sense, they both teach the path of moral safeguarding. The lion cubs at the top are the protagonists in the story of the Physiologus, the Christian naturalist and symbolist didactic text which equates the beast with Christ. The cubs, it is said, are stillborn, but the lion manages to revive them three days after birth by blowing on them. God the Father, also on the third day, rescued his Son from the dead. The comparison with Christ’s resurrection is therefore immediate and direct. In their foetal position, the lions reaffirm this identity and, in the monk’s view, focus the capital on the resurrection of man, enhancing the regenerative sense of the other animals.

CAPITAL 36. LIONS, LION CUBS AND EAGLES

Capital 37. Basket of acanthus leaves

In the northern wing of the cloister, compositions formed by acanthus leaves inspired by the ancient Corinthian capitals begin to appear with certain frequency.

At Silos, such baskets, with a marked geometric character, often have rows of overlapping leaves, with angled scrolls at the top, which are shown scalloped with protruding threads in the form of ribs. The tips are noticeably thickened, sometimes folding in on themselves and sometimes appearing as fruit in the form of berries or false berries hanging from them.

CAPITAL 37. BASKET OF ACANTHUS LEAVES

Capital 38. CYCLE OF THE INFANCY OF CHIRST: ANNUNCAITION, VISITATION, NATIVITY, ANNOUNCEMENT TO THE SHEPHERDS, FLIGHT INTO EGYPT

This capital, dedicated to the coming into the world of Christ, marks the beginning of a new stage in the cloister, which was produced years later, in the second half of the 12th century. Two capitals further on, it is immediately accompanied by scenes from the narrative of the Passion, both of which constitute the only reference point of the cloister capitals. The new arches, like the older ones, are based on and emphasise animals, except that the mythical and fabulous explanation is abandoned and becomes a pure symbol of theology and morality. However, this does not mean that glimpses of its origins do not appear with some frequency.

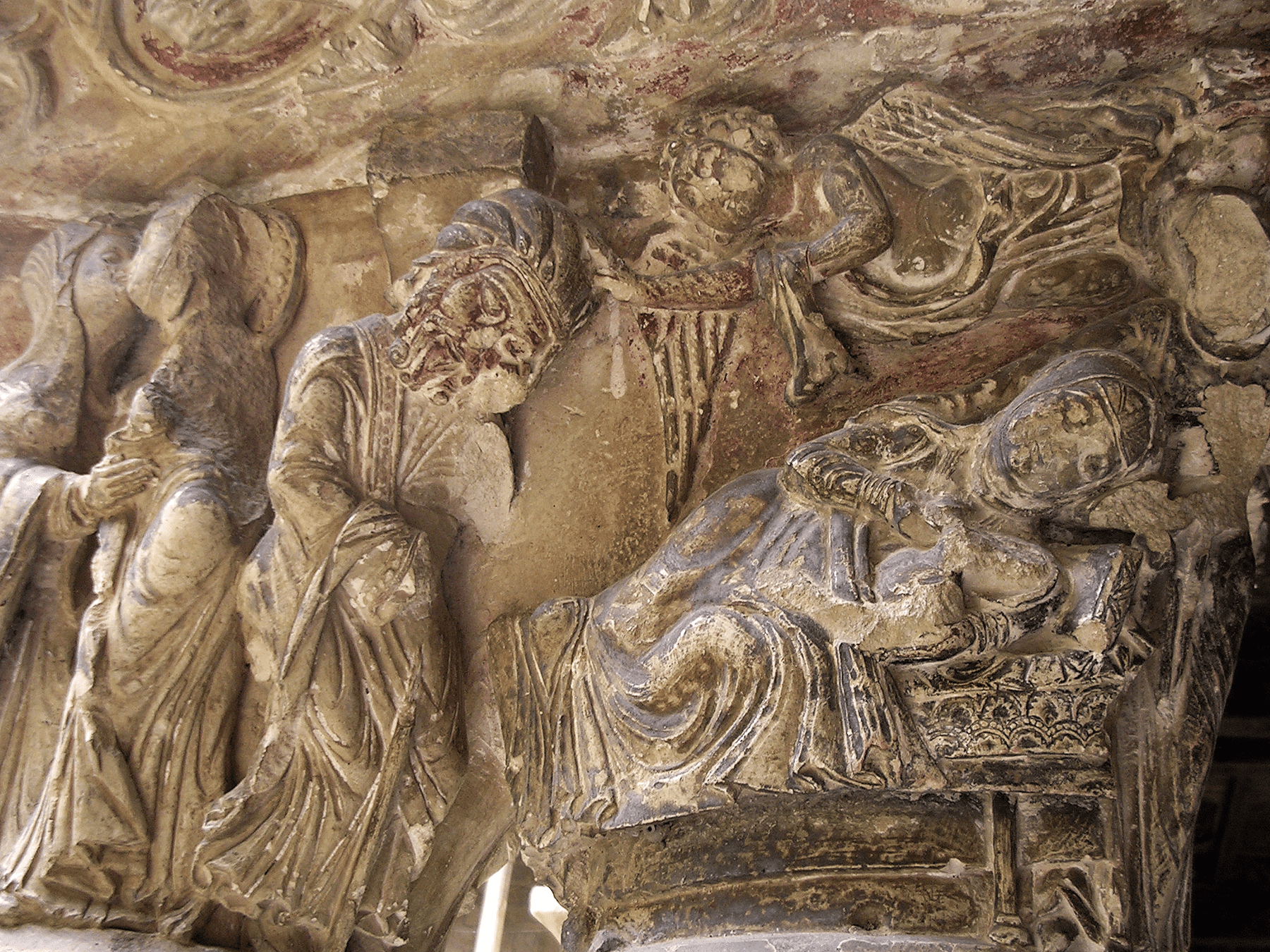

On the side facing the garden, the capital introduces the story of the Annunciation – the archangel Gabriel’s visit to Mary to tell her that she would conceive through the Holy Spirit. Both standing, their hands expressed the transcendence of the encounter, almost imperceptible today due to the deterioration of the stone. Gabriel conveys the divine message with the heralds’ staff, held in his fist and still visible. In response, the Virgin Mary places her hand on her breast as a sign of acceptance and submission. In the adjoining space is the Visitation – the meeting between Mary and her cousin Elizabeth. It is reduced to an effusive kiss and, alongside, a sleepy Joseph receives the angel’s news of his wife’s conception through a light touch on his head.

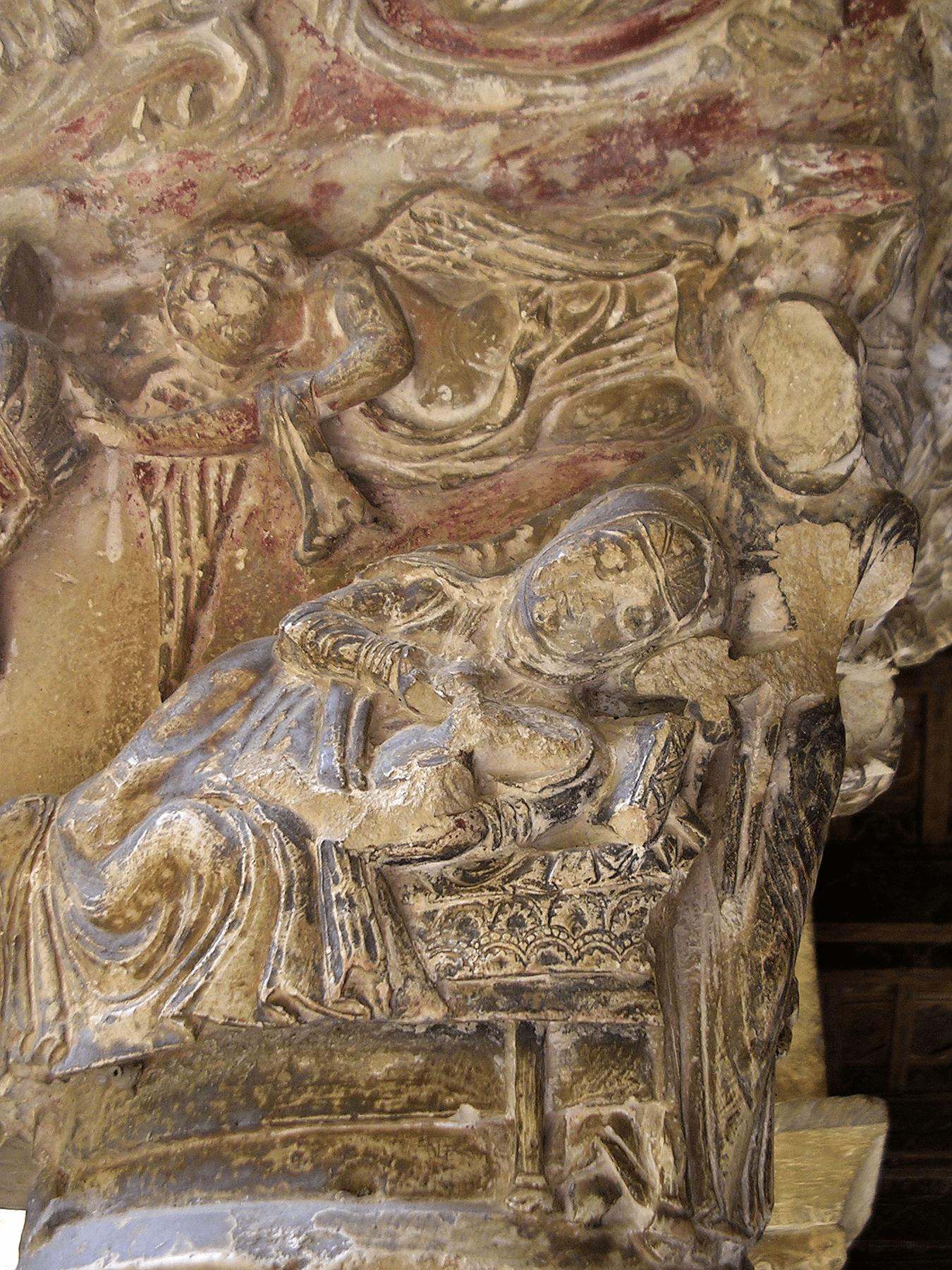

In the Nativity vision, Mary lies on the bed beside the Child, and the same angel who brushes Joseph on the head, hovers over mother and child in an act of praise. At the head of the bed, a half-seen midwife holds out an arm towards the new mother.

Then, under an arch, the Child, warmed by the breath of the ox and the mule, receives the adoration of the angels bearing censers.

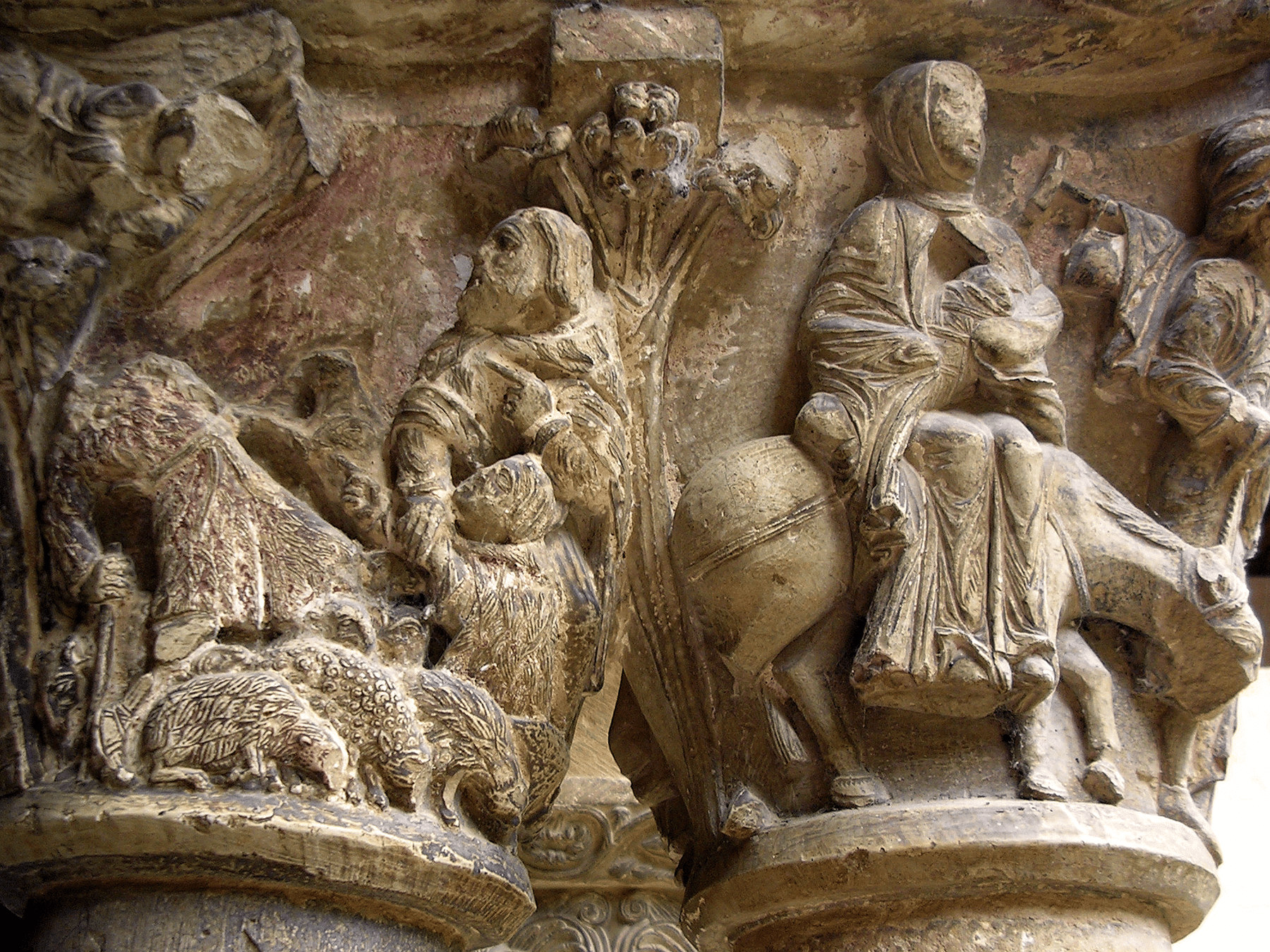

Next comes the Annunciation to the Shepherds, where the artist depicts the shepherds tending their sheep. There are three in particular who are awed by the barely visible angel’s appearance and announcement from above a bush and without any interruption, that is to say without the usual Adoration of the Magi, the artist represents the Flight into Egypt. Mary, seated on the donkey, occupies the rest of the capital’s façade. Wearing a neckband, she protects the swaddled infant with her own mantle. Joseph leads the procession holding the donkey’s halter, while the animal, in an anecdotal detail, tries to bite his leg. With a crook on his shoulder, from which hangs a cloak and a pouch, he shows that he is a traveller, and to one side, as with the Annunciation, he is the figure that closes the cycle.o.

CAPITAL 38. CYCLE OF THE INFANCY OF CHIRST

Capital 39. Dragons

In the theology of the time, the dragon represents the devil. It stalks souls with hidden temptations, it infects thoughts with pride, and it poisons words, leading man to commit evil deeds. Some authors, instead of naming the dragon, the devil, tell its origin story – the fallen angel whose name, “Samael” means “contrary to God”. He pretended to be equal to God and even to surpass Him, although his stay in heaven lasted only a short time, about an hour. Together with other angels also desirous of prevailing over their fellows, he was cast into hell – a place situated in the depths, comparable to a “prison” and an “abyss of death”.

The dragons are arranged with their bodies attached. However, a deep twist intertwines and separates their necks to better isolate and emphasise the heads, while creating a space between them in order to show floral ornamentation, very prolific in this capital. The deformity of their heads is portrayed through huge jaws, flattened noses and eyes bulging from deep sockets. Their reptilian necks are elongated to favour their inflection, while their nudity is surprising, with no traces of scales, broken only by the presence of a “crest”, as described by naturalists from antiquity.

This is a fabulous animal and, as such, its body is made up of different organs, alien to each other, combined in an unreal but striking amalgam: the body of a bird covered with scales, the wings of a bird of prey, the tail of a reptile and the legs of an ungulate topped with hooves. As an exception and attributable to the whim of the artist, one of the dragons has claws instead of hooves. This is Satan, the “king of all evil”.

From the tails themselves emerge the stems that invade the capital, while between the heads of the monsters a hooped, grassy fruit, similar to a pineapple, sometimes emerges.

CAPITAL 39. DRAGONS

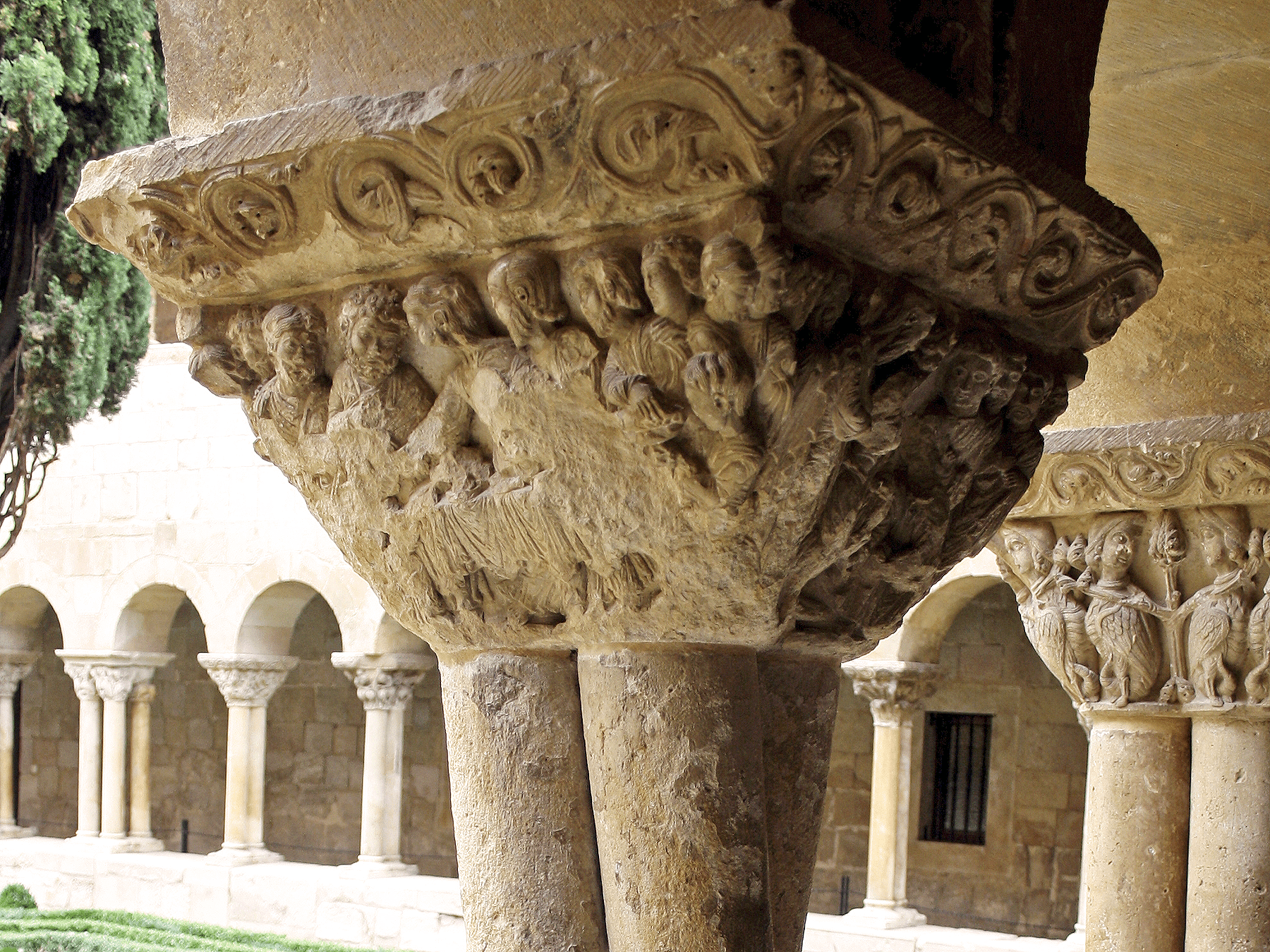

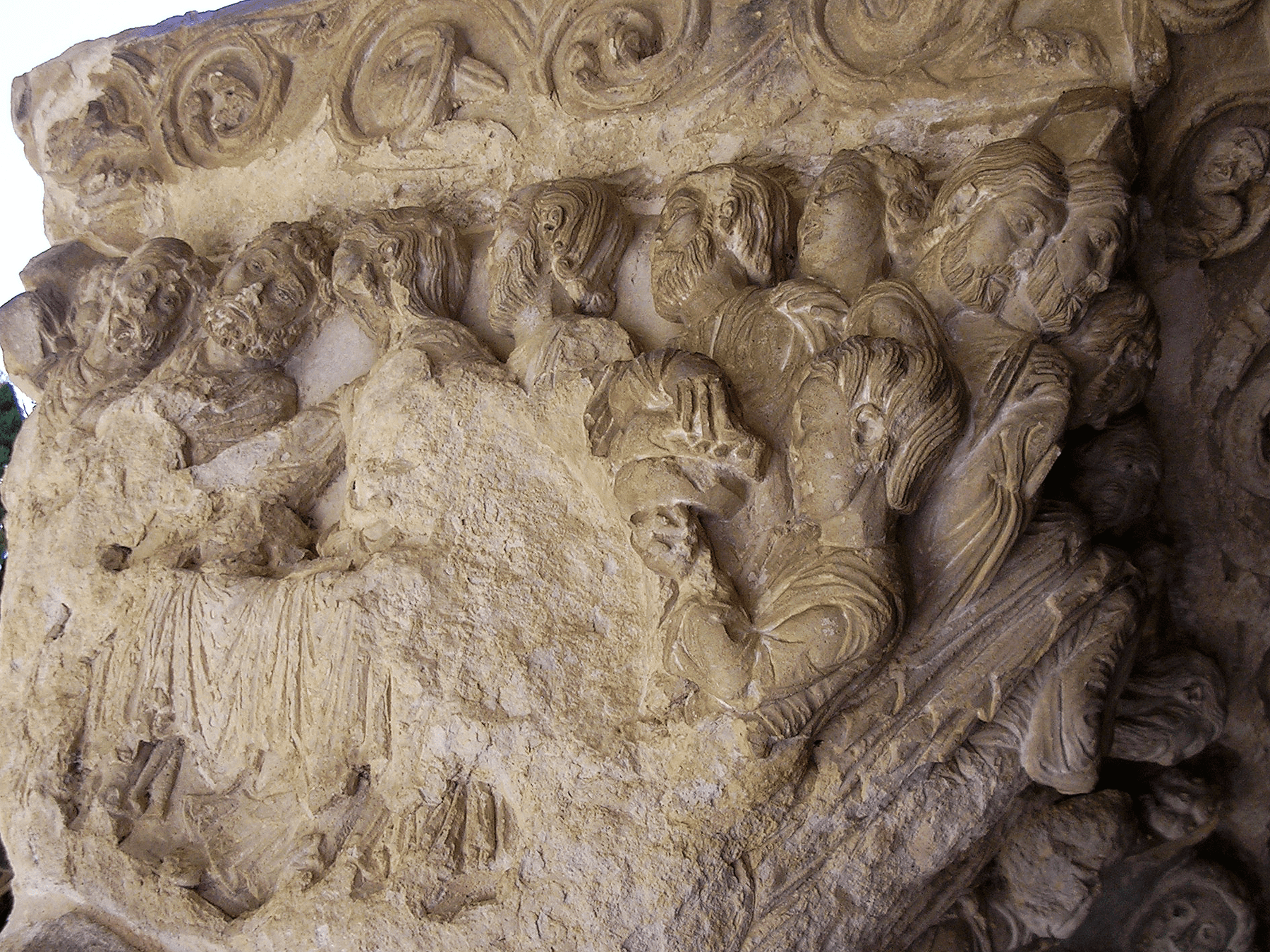

Capital 40. Preludios de la Muerte de Cristo: Entrada en Jerusalén, Última Cena, Lavatorio de Pies

Excessively mutilated, the capital dedicated to the Passion barely gives a glimpse of its scenes: the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the washing of the feet.

In the first scene of the story, Christ, astride a donkey, enters the city of Jerusalem; and below the donkey we see her colt, as mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew (21:2). Jesus is accompanied by two disciples and perhaps Peter could be identified by his curly hair, an unmistakable sign of his image in medieval iconography. All three have halos, although only Christ has the crucifix halo marked with a cross as a sign of his martyrdom.

“The children of the Hebrews” receive him with a roar. Some take off their vestments to carpet his passage as others climb or try to climb a tree to get a better view of the Nazarene. Little else is discernible. On the other side of the capital, older people are also watching the small procession pass by from behind the tree – only two are clearly visible. In the background, the walled city of Jerusalem, now barely visible, concludes the scene.

In the Last Supper, despite the erosion, Christ can still be seen presiding at the table surrounded by his disciples, with the head and perhaps the bust of Saint John leaning on Jesus’ chest visible. Isolated in front of the table, possibly kneeling so as not to obstruct the overall view, is Judas. Christ points him out as a traitor by stretching out his arm to give him a morsel of wet bread (John 13:26) as the apostles turn their gaze to him. The curly hair reveals Peter on the Lord’s right, while from the left side of the table emerges a beardless young man, apparently carrying food for supper.

On the western façade of the capital, another badly worn relief, The Washing of the Feet, shows the figures somewhat more defined and denotes the presence of the apostles around a kneeling Christ, who, presumably with the help of a basin and a towel around his waist (the area of the capital is very eroded), washes Peter’s feet. Surprised by this action, the disciples wait their turn. Some of them appear to hold cloths over their shoulders to wipe their feet. Peter’s expression, however, is indiscernible, as he gazes at his Lord.

CAPITAL 40. Preludes to the death of Christ

Capital 41. Bird-mermaids

This capital of bird-mermaids continues the bestiary that, interspersed with vegetal themes, will complete the ornamentation of the cloister’s arcades.

The mermaids are shown facing each other, two by two, with their heads in different postures to those of the bodies – when they face each other, the heads are opposed yet if they appear with their backs to each other, the heads turn to look at each other.

Trees dominate the centre the front-facing façades of the capital. Far from being leafy, they are reduced to a trunk and lateral branches that advance towards the neck of the mermaids and create, behind their heads, a play of fleshy leaves, curled in on themselves, together with the leaves from the adjoining mermaids, as was typical of this new workshop.

The female heads and bird-like bodies proclaim their identity: they are bird-mermaids. However, the tails and the scaly skin of the reptiles, as well as the hoofed feet of the ungulates, achieve an animal symbiosis that accentuates the evil of an already diabolical image. The female faces are embellished with short, curly manes, covered by a headdress, although the deformity appears in the long hair which, from the collar and half-hidden by the branches, hangs over their necks.

As could be seen in the old part of the cloister, within Christian symbolism this became a symbol of lustfulness and sins of the flesh.

CAPITAL 41. BIRD-MERMAIDS

Capital 42. Acanthus leaves

This capital repeats the basket of overlapping acanthus leaves, attached to a background whose lush outline is crowned with thick scrolls.

CAPITAL 42. ACANTHUS LEAVES

CAPITaL 43. Lions and Trees of Life

Lions and trees combined with wild beasts form the next capital. With the texts of the time in the background, these trees can be identified with the “tree of life” – the tree of paradise that freed man from old age, sickness and death. Due to their sin, Adam and Eve did not get to taste its fruit. In this capital, these trees that feature some foliage at the top, are interspersed between each of the animals that turn their heads, contrary to the direction of their bodies, to look at the trees.

The most suggestive feature is to be found on the south-facing façade of the capital, on which the presumed tree of life houses a winged dragonkin within its branches. Interestingly, on this side of the cylindrical block the lions turn their heads away from the reptile, as if avoiding its vision.

In the theology of the time, the symbolism of the lion often oscillates owing to its duality between the Antichrist and Christ. Here, his sense of harmony with the tree makes him favour the lion-Christ, since God-Son with his death annulled Satan (the dragonkin), reopening the gates of paradise and access to the tree that brings immortality.

CAPITAL 43. LIONS AND TREES OF LIFE

CAPITaL 44. Acanthus leaveS

The overlapping leaves are repeated, except that here, the relief of some of the palmettes is enhanced by their curved edges.

CAPITAL 44. ACANTHUS LEAVES

CAPITaL 45. Bird-mermaids

The bird-mermaids reappear, this time facing the spectator, although with their original appearance: a bird with a woman’s head. Here, too, the plant element separates the mermaids from each other. However, it is not a tree but a bush with lateral, fleshy branches, half-hidden for the most part by the spreading wings of the mermaids.

The formal beauty of the faces, framed by long manes, is a factor in their nefarious power of seduction, correlative to lasciviousness.

CAPITAL 45.-BIRD-MERMAIDS

CAPITaL 46. ACANTHUS LEAVES

The overlapping leaves are repeated, except that here, the relief of some of the palmettes is enhanced by their curved edges.

CAPITAL 46. ACANTHUS LEAVES

CAPITaL 47. Griffins

Twelfth-century theologians cite this animal as a “monster of India”, with the body of a lion and the wings and claws of an eagle. Essentially, this is the griffin of Silos, although the craftsman sculpted it with the typical features of his time: the body of a lion, with its corresponding claws, the head and wings of an eagle, pointed ears and a goat’s beard. In mythology, the griffin is the most fearsome guardian of the exuberant riches of its place of origin, namely the regions of Scythia and Hyperborea and their wealth of gold and precious stones.

A leafy tree accompanies the griffins in the centre of the front faces of the capital. The crown of the tree canopy is populated by branches and leaves, while on the other side, branches slide and fork through the bodies of the beasts: again, it is the Tree of Life.

In Christian culture, its ambivalence as a lion and an eagle is decisive in the allegorical evaluation of the animal. Its satanic character is confirmed, which is not the case in Silos. Here it has a reptilian tail that recalls of a dragon, as appears in other reliefs. The presence of the tree, on the other hand, strengthens the more edifying hypothesis. The griffins would act as custodians of the Tree of Life. How blessed are those who, like the lion and the eagle, in their incarnation of virtue, combine the vigilance and courage of the lion with the eagle’s yearning for elevation to reach divine contemplation. They would therefore be the righteous awaiting their access to immortality, represented in the tree.

CAPITAL 47. GRIFFINS

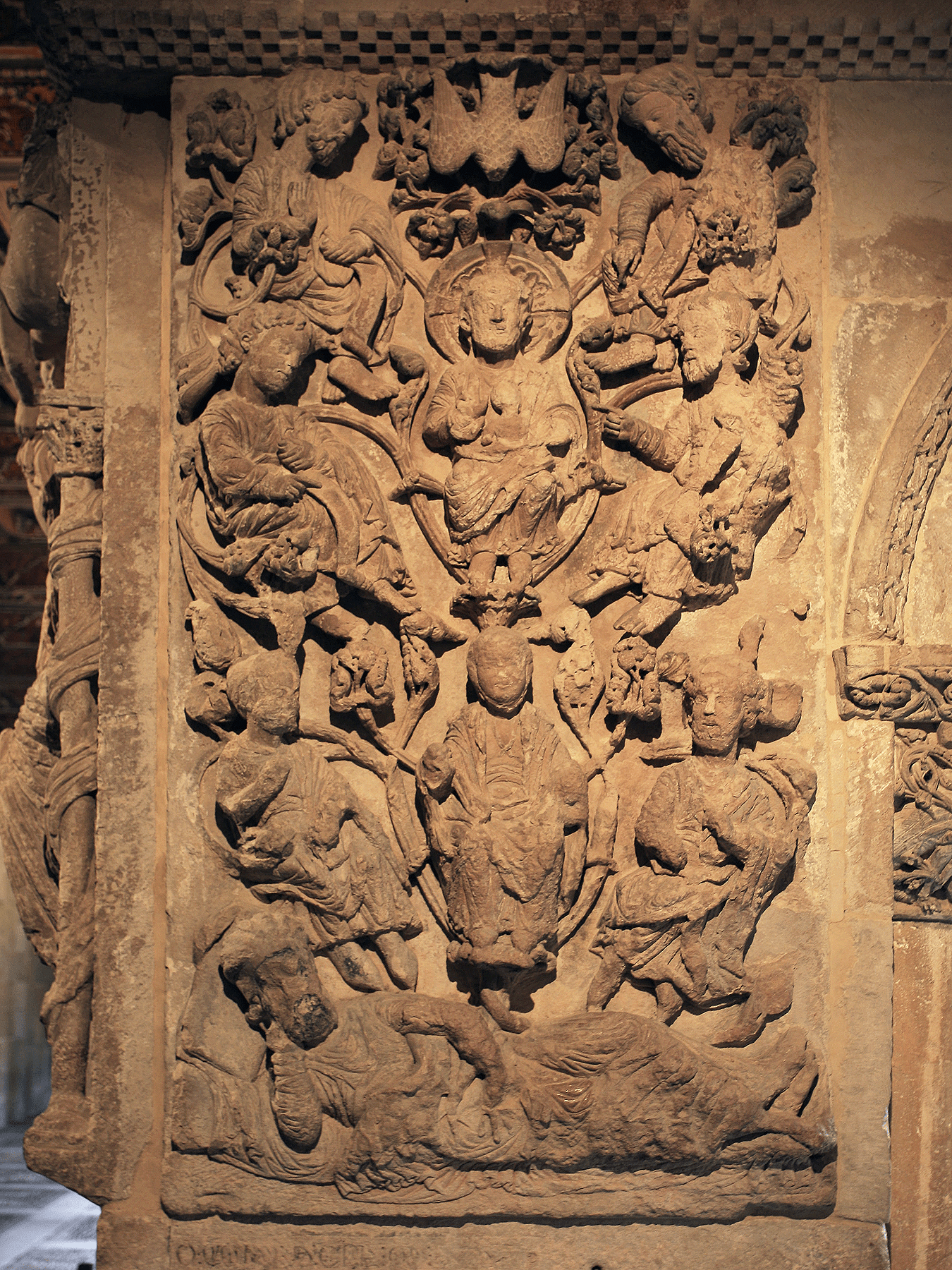

The Tree of Jesse, sculpted on the south face of the pilaster in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, underlines the dual nature of Christ – the divine lineage, as is logical – enters into the Trinity, and the human lineage, into Mary and her forebears. In the lower part of the relief, it therefore represents Christ’s human lineage, while in the upper part it depicts his divine character through a Trinity.

Priests and theologians unanimously accepted that Christ the man came from the lineage of King David; however, inspired by a prophecy of Isaiah, his family tree was rooted in Jesse, David’s father: “And a staff shall grow out of Jesse’s trunk and a branch shall sprout from his roots.” They saw the Virgin Mary in the bud, in the staff and Christ in the branch. The tree of Silos therefore centres on the figure of Jesse – asleep on a bed and in a tilted posture to facilitate the vision of the “rod”, born in his side and the genesis of the Virgin. The “rod” opens in the form of a mandorla: an ideal frame to enhance the image of the seated Mary. Nonetheless, its head remains free of the oval (open and foliated at the top), as it emerges from the “stem” where God the Father sits in another similar mandorla giving his blessing. Here we see the break with the conventional Tree of Jesse. Attentive to the human lineage, the Virgin Mary precedes Christ in this genealogical tree. In Silos, on the other hand, the Son is replaced by the Father because, without any fissure, a Trinity is created in proof of its divine nature. The Trinity is reflected in the Father with the infant Son between his knees, while the dove, placed on high, symbolises the Holy Spirit. The Child in the arms of the Father defines the representation of the Trinitas-Paternitas.

While Isaiah’s prophecy alludes exclusively to Jesse, the Virgin and Christ, in the “genealogy of the Saviour” the Apostle Matthew cites his intermediate generations. In the Silos relief, this is also summarised in the two figures that frame Mary: possibly King David and King Solomon with their respective attributes (the David’s lute and Solomon’s turban). Around the Trinity, the side figures bear phylacteries. These are prophets – spiritual rather than carnal forefathers. They might be the four major prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, the latter young and beardless as he used to appear.

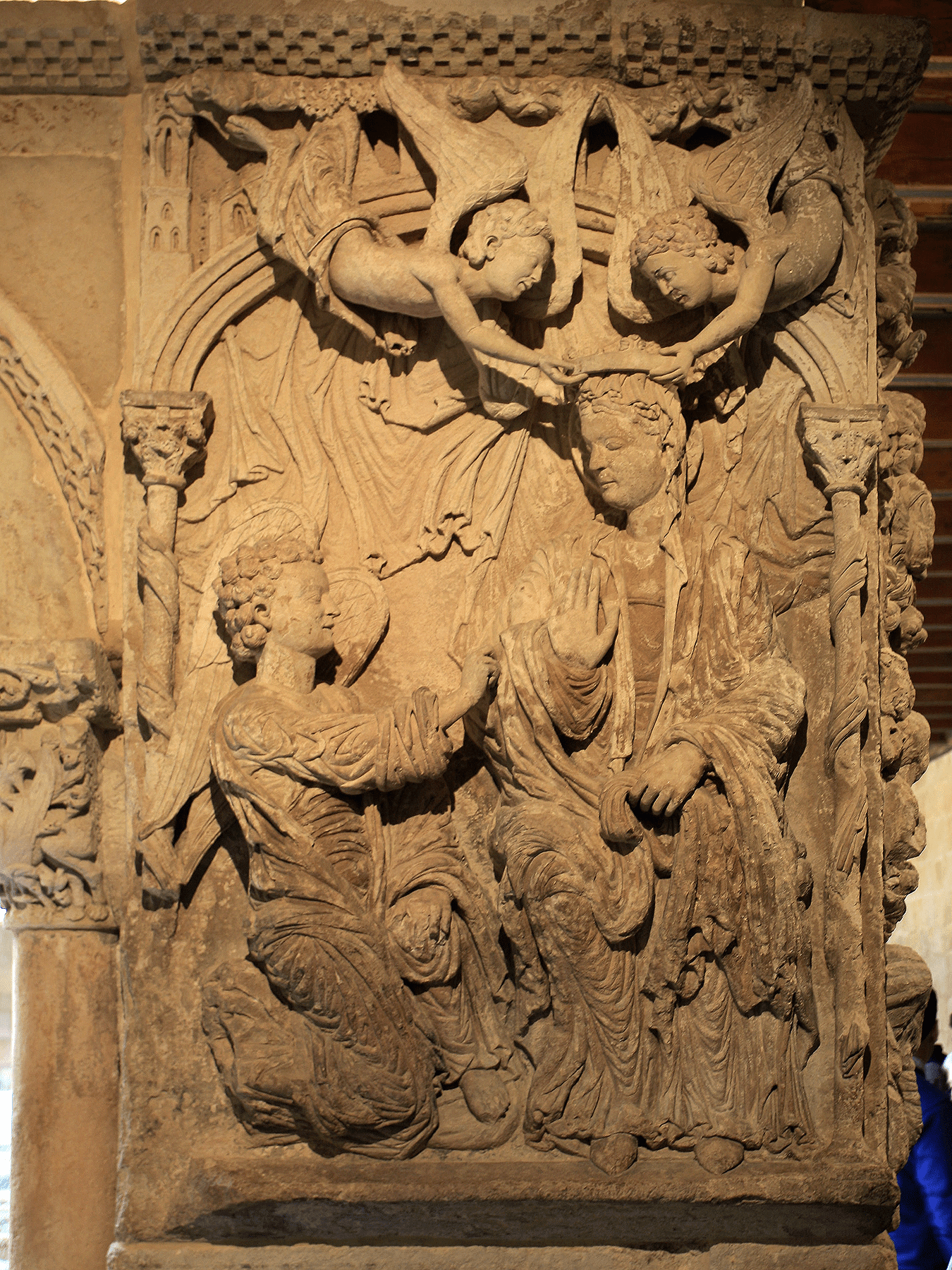

The western part of the pilaster is firstly connected with the Marian fervour that was strong in the 12th century and secondly, with the Trinitarian dogma and the nature of Christ, depicted on the other side of the pillar. In relation to the Father, the nuptial mystery emerges in which God becomes her husband. The relief recalls the origins of her conception through the presence of the Archangel Gabriel. The Holy Spirit mediates the miraculous fertilisation. Finally, Christ, the Son of God, manifests his earthly filiation by emerging from the womb of the Virgin Mary. Her beloved Son.

Her final triumph in heaven, crowned by angels, indicates that she also accompanies him in glory and shares in his resurrection.

RELIEFS OF THE SOUTH-WESTERN PILASTER. THE TREE OF JESSE AND THE EXALTATION OF MARY

CAPITaL 49. FERNS

The capital features ferns, although the complexity of the composition blurs their simple appearance. Its stems rise up from the talus bone. As they ascend the capital, they produce different leaves, some of which are linked by large feathery fruits.

CAPITAL 49. FERNS

CAPITaL 50. EAGLES

The eagles return, however, in this case, with Trees of Life, of Immortality, in the centre and at the corners of the cylindrical block, separating the pairs of opposing eagles. They contort their heads to nibble at the upper branches of the tree, close to the top, while the lateral branches of the trunk seek the bodies of the birds.

In the new symbolic perspective of this second stage of the cloister, the eagle is equated with Christ. Its flight reaches a heavenly height, while Christ has entered the highest heaven when He walks alongside the Father. In this capital, intertwined with the Tree of Life, the Christ-eagles reaffirm the immortality of the blessed.

CAPITAL 50. EAGLES

CAPITaL 51. ACANTHUS LEAVES

This capital repeats the basket of overlapping acanthus leaves, attached to a background whose lush outline is crowned with thick scrolls.

CAPITAL 51. ACANTHUS LEAVES

CAPITaL 52. DEER

The capital, in which the image of the deer is half-hidden by a plant motif, announces its symbolic projection: the deer, carved to perfection in their smallest details – branchy antlers, short tails and hooves of ungulate hooves – evoke the catechumen, the baptised from the earliest times of Christianity. The mesh of leaves and stems, which emerges from a trunk perched on the talus of the front faces of the capital and clings to the deer in the form of meanders, hints at the harassment of the vices.

The stags are reminiscent of the “stag caught in a snare” in Proverbs, in reference to the faithful caught up in the temptation of lust. Meanwhile and in contrast, they suggest the safeguard of divine providence, as the Psalms sing, ready to regenerate man and to protect him, precisely, from the “hunter’s snare”.

The tangle of vegetation, comparable to the “snare” of the Old Testament, imprisons the deer, imprisons the faithful. But, at the same time, he discovers the man eager for “living water”, the deer-catechumen, capable of renewing himself and overcoming his passions with God’s protection, according to Psalms.

The artist subtly expands the stems over the bodies of the deer so that their thickness does not obstruct the visibility of the figures. The leaves, on the other hand, fleshy, folded and ideal for filling any space, are relegated to the upper and lower areas of the cylindrical block or to the hollows of the relief, just where they barely conceal the silhouette of the deer.

CAPITAL 52. DEER

CAPITaL 53. DRAGONS

The dragons reappear in this new capital, although their bird-like pose and broad, somewhat flattened countenance, without the prominent snouts common to these animals, forge an image different from that of their fellows.

However, the similarities with other dragons are evident: bird-like bodies covered with apparent scales, raptor-like wings, reptilian tails and ungulate feet with hooves. On the other hand, the faces do make a difference, as the looseness of their size allows the artist to make certain significant aesthetic changes.

The eyes remain large and protruding, the deep sockets, the upper edge of which simulates eyebrows, are maintained while the eyelids are carefully crafted and the pupils are pierced as a striking visual effect. However, as has been pointed out, the noses and mouths do not take the form of a snout, a plastic resource which is basically the reason for their disparity with the conventional figure of the monster. They certainly have the same excessiveness – the pierced nostrils remain although the jaws are blunt and, moreover, open to show their teeth and incisors, sharp and threatening, a sure testimony to their fierceness. The deformity culminates in strange long hair, no forehead, large, pointed ears and, again, long hair covering necks.

In this capital, the opposing and facing dragons, with their routine interplay of heads, prevail over the plant decoration, reduced to extremely simple trees.

CAPITAL 53. DRAGONS

CAPITaL 54. Lions and Trees of Life

This symbolic representation is similar to capital 43 in the western gallery.

CAPITAL 54. LIONS AND TREES OF LIFE

CAPITaL 55. Onocentaurs

This very deteriorated capital shows the presence of a new hybrid creature, with a human torso and a donkey’s rump, known as an onocentaur. Its resemblance to the classical centaur, half man and half horse, could raise doubts about its identity. However, in the doctrinal framework of the cloister there is only one biblical image: that of the onocentaur – cited in the Old Testament by the prophet Isaiah, disseminated by the Physiologus, the Christian naturalist of the 2nd century, and therefore present in medieval bestiaries.

The aspect of man-as-not obeys the Physiologus’ own description and his dual nature warns of the possible “animality” of man when he is dominated by instincts over reason and reaches the unbridled passions, centred, fundamentally, on sexual ardour.

Here in the capital, the onocentaurs oppose each other’s bodies, but turn their torsos to do battle. They appear to be armed and the bristling hair, still discernible, underlines their fury. According to the theologians, in their accounts of the punishments of hell, “chains will bind all their limbs”, because the reprobate have “consecrated” their lives to vice. Similarly, on the capital, a tangle of stems and leaves that are seemingly “chains” oppress the onocentaurs.

CAPITAL 55. ONOCENTAURS

CAPITaL 56. Bird-mermaids

Although the deterioration of the stone prevents us from appreciating details, we can perceive a mermaid theme that is very similar to that of capital 41.

CAPITAL 56. BIRDS MERMAIDS

Capital 57. Fight between men and dragons

In this capital, which is also badly destroyed, the human figure appears integrated into the bestiary for the first and only time. Interspersed with the foliage, it appears in the form of small, dynamic characters in disparate postures, attacking and defending themselves from the dragons at their feet.

Despite the damage to the relief, the original composition can still be glimpsed: for example, the presence of two human figures, on the front faces of the cylindrical block, attacking two dragons in an attitude of attack, possibly with spears. In the centre, between both figures and at the same height, a mermaid-bird – adorned with a cape and carved loosely, perhaps with her wings spread – which seems to indicate her as an enemy to beat. On the narrower side façades however, a single man faces two dragons, apparently even more aggressive and dominant; if they do not devour, at least they reach their legs and feet. They defend themselves against their harassment by means of weapons, which today are barely visible. Perhaps a mace on one side, a shield and spear on the other. Finally, new combatants in a fighting pose can also be seen in the corners of the capital, although they are now very unclear. At least one of them, apparently armed with a bow, may have been firing an arrow aimed at the siren.

The relief is based on and reproduces one of the theological principles of the medieval world: the struggle of man against Satan. The mermaid, emblem of lust, is introduced into the message with some relevance to further strengthen the thesis that the assault upon the flesh prevails among the demon’s endeavours.

CAPITAL 57. FIGHT BETWEEN MEN AND DRAGONS

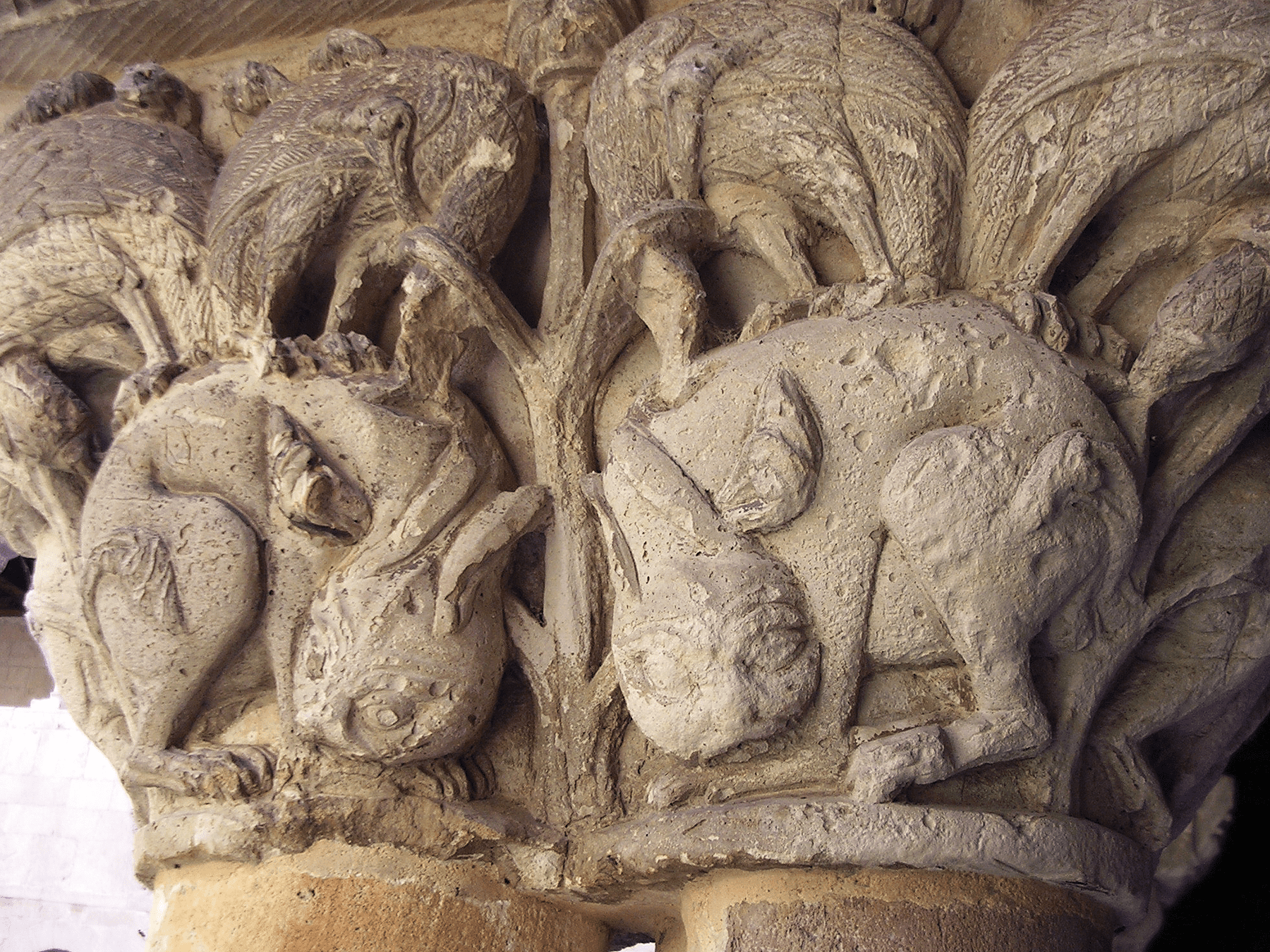

Capital 58. Hares attacked by eagles

The scene realistically depicts the voracity of eagles tearing at the flesh of defenceless hares. Their corpulence, however, is strange, even if it can be interpreted as a necessary artistic resource that allows each of the hares to withstand the weight and harassment of two eagles at the same time: one dedicated to destroying its neck and the other to tearing its back to pieces. The raptors’ attack is thus unrelenting and unrelenting.

Trees with small crowns, in short, the hoop’s own gannet sheltering the grassy fruit and meagre branches stand between the hares. The lower branches advance precisely towards them, either on their haunches or next to their heads. The upper branches, on the other hand, curl around the eagles’ necks and divert the leaves towards their wings or backs. In the corners, the trees generate a new branch, close to the top, which lands on the birds.

Here in relief, the hare seems to illuminate the meaning of the eagle and of the capital as a whole. The hare, in the symbolic interpretation of the Middle Ages, was often equated with lust. Thus, we see a re-emergence of the legacy of the Physiologus who attributed his extremely prolific fecundity to insatiable mating, synonymous with lasciviousness.

In keeping with the theological sources from the 12th century, the eagle approaches divine meanings, with this quality associated with the incontinent nature of the hare. In this capital, the eagle – Christ – is depicted as attacking lust, a threat to the moral integrity of man, whether he be a layman or a monk.

CAPITAL 58. HARES ATTACKED BY EAGLES

Capital 59. Ferns

The representation of ferns is repeated. The capital features ferns, although the complexity of the composition blurs their simple appearance. Its stems rise up from the talus bone. As they ascend the capital, they produce different leaves, some of which are linked by large feathery fruits.

CAPITAL 59. FERNS

Capital 60. Capital without decoration

Restored with the pyramidal trunk shape without carving.

CAPITAL 60. CAPITAL WITHOUT DECORATION

Capital 61. Eagles

The representation of the eagles is again emerging.

CAPITAL 61. EAGLES

Capital 62. Onocentaurs

The onocentaur seemingly reappears, this time more similar to the image of the classical centaur. However, the uniqueness of the capital lies in the disappearance of the axis of the relief in the form of a tree or a small flower, usual in almost all the capitals, and the presence in its place of a voluminous onocentaur. This is framed by two trees, since vegetation, in one way or another, is consubstantial to the workshop’s compositions. The branches are grouped near the crowns, formed only by the arum plant that conceals its fruit. They divide the leaves towards the necks of the onocentaurs, on their capes or towards the hollows of the relief.

CAPITAL 62. ONOCENTAURS

Capital 63. Dragons

Here, the dragon series is clearly outlined, since, as an exception, it has no plants nearby.

CAPITAL 63. DRAGONS

Capital 64. Griffins

Almost identical to the representation in capital 47.

CAPITAL 64. GRIFFINS